What Democrats Can Learn From Denver

How to Create the Virtuous Cycle

A lot of times we focus on what Democratic cities can do better, but it’s also important to highlight and learn from the cities who are getting things right. My colleague, Tahra Hoops had a piece earlier this week on how San Diego has achieved considerable success on the housing front.

Another city that Democrats should draw lessons from is Denver. Quietly, Denver has become a really amazing city with a thriving job market, a wealth of amenities, strong cultural scene, good schools, and it’s family friendly. It’s a pretty terrific combination! How did they do that? By letting the market build housing to meet supply, investing in high quality transit, adopting a business-friendly approach, and leaning into great parks and green energy.

Letting the Market Add Housing Supply

Denver has done something crucial that many blue cities have conspicuously failed at: it let developers build housing. While places like San Francisco and Seattle spent the 2010s wringing their hands over new apartments, Denver just built them. The city added over 115,000 residents during that decade while constructing enough housing to accommodate much of that growth. Housing still isn’t cheap (it’s a desirable place to live so there’s lots of demand), but it has meant that costs haven’t spiraled into the catastrophic unaffordability that defines some other cities. This development is ongoing: there’s a new 62 mixed-use development called The River Mile that’s going up now and is expected to add another 8,000 units of housing.

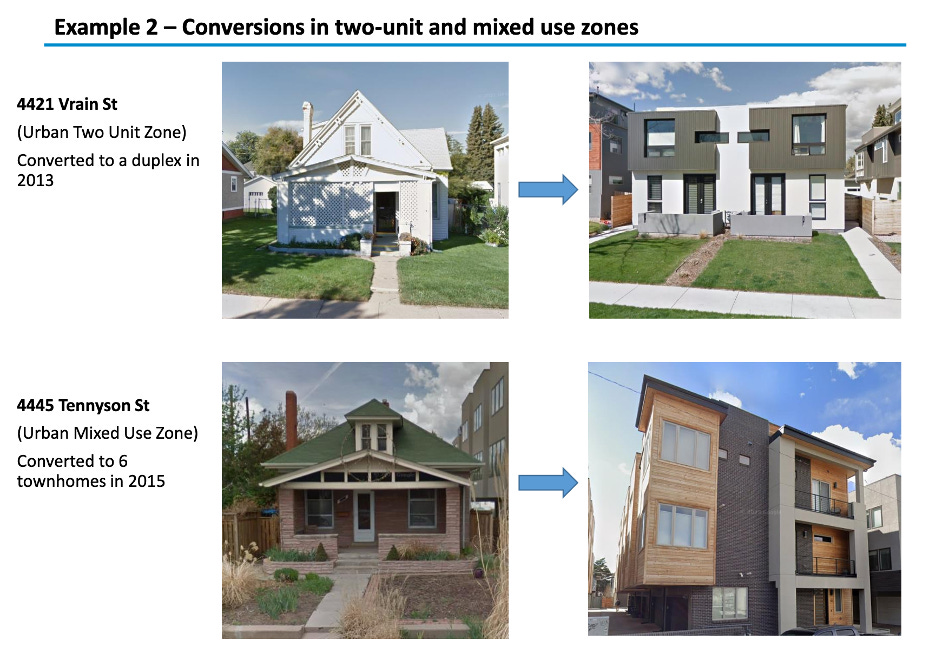

Denver, unlike those other places, has been willing to let the market respond to demand. In 2010, the city updated its zoning code in a way that allowed for more development in a number of areas. This allowed for many properties to be converted to more housing units, as you can see in the example here.

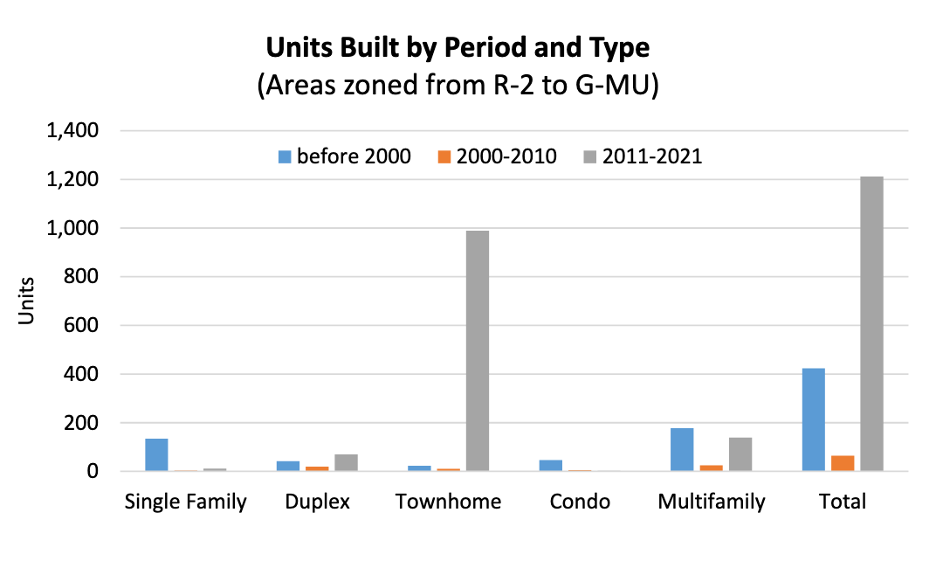

It also facilitated a boom in townhouse construction, which you can see here by comparing the grey lines (2010s) to the orange lines (2000s). And note that these numbers aren’t for the whole city, they’re for just one kind of area in the zoning code.

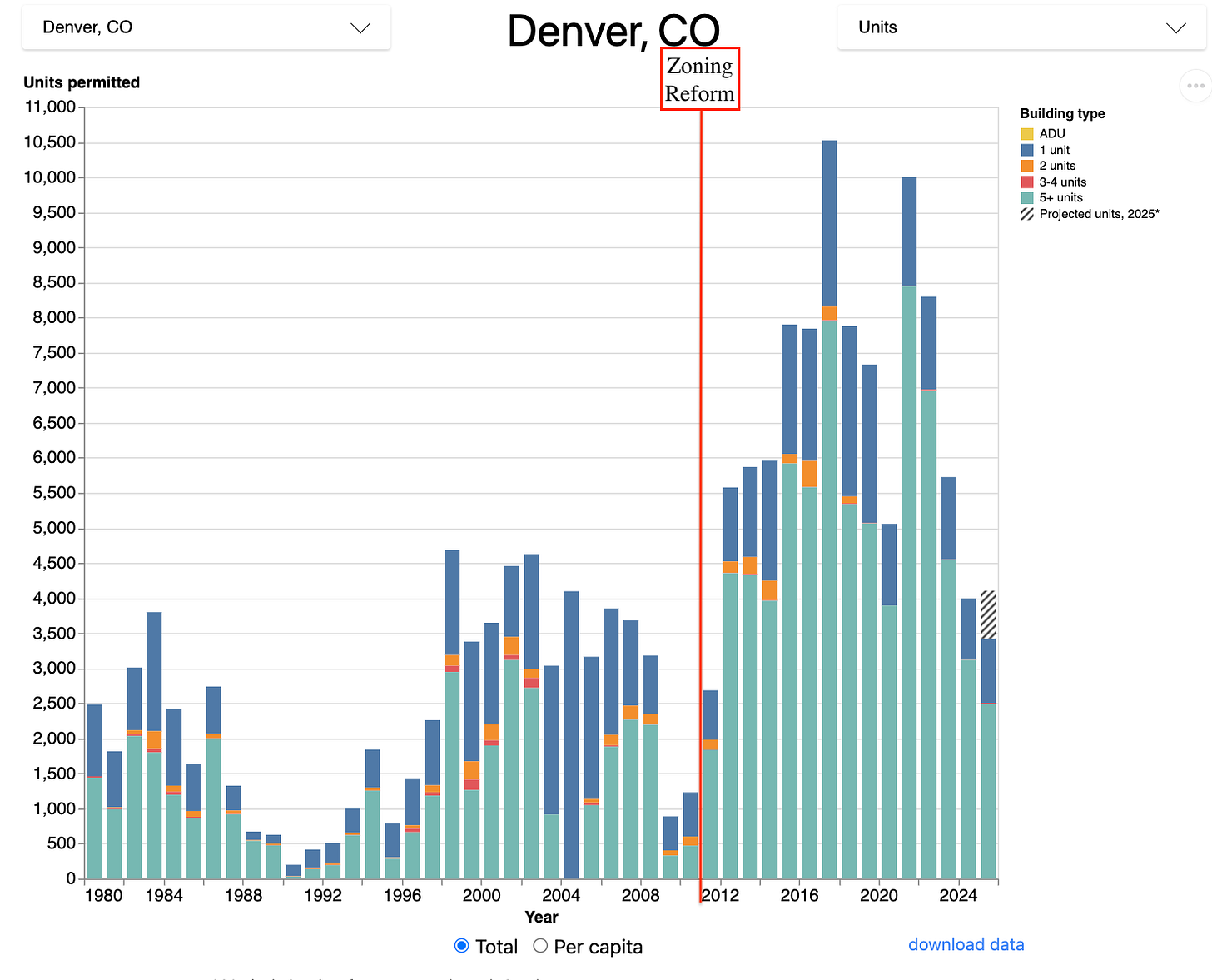

For the city as a whole, you can see a clear difference in the amount of housing built before the more development-friendly zoning and after. Think also about the national context. The 2000s were very favorable to building lots of new housing. The 2010s were not. And still, because of zoning reform, Denver was able to build far more housing in the 2010s than they had in the 2000s.

Denver also allowed denser development near transit corridors, and in 2024, the state of Colorado passed a new law taking these reforms even further. This regulatory environment has made it a lot easier to build. This has passed through to lower rents. All of this construction has directly led to rent drops averaging 5.9% over the last two years, with the most affordable class of apartments seeing rents fall by a whopping 10%.

Moreover, by allowing growth, Denver generated the tax revenue and economic activity that funds other priorities. New development means new property taxes, more transit riders, more customers for local businesses. By contrast, cities that strangle housing supply don’t just make housing expensive; they starve themselves of the resources needed for everything else.

This is the first step in Denver’s virtuous cycle. You can’t have good transit without riders and revenue. You can’t maintain parks without a tax base. You can’t keep a city functional if working-class people can’t afford to live there. Denver understood that letting the market add housing supply is the way to build momentum in the right direction on all of that.

With regards to homelessness, Denver has avoided the encampments seen in places like San Francisco, Seattle, and Portland. The big difference there is enforcement. Denver invested in shelter capacity and services while also consistently clearing encampments and enforcing laws against camping in public spaces. Services matter, but so does enforcement. At a certain point, you have to decide that public order and ensuring families have access to the public services their taxes pay for is the main priority. If you want a great city, you can’t have disordered public spaces that middle class families are uncomfortable using.

Getting Transit Investment Right

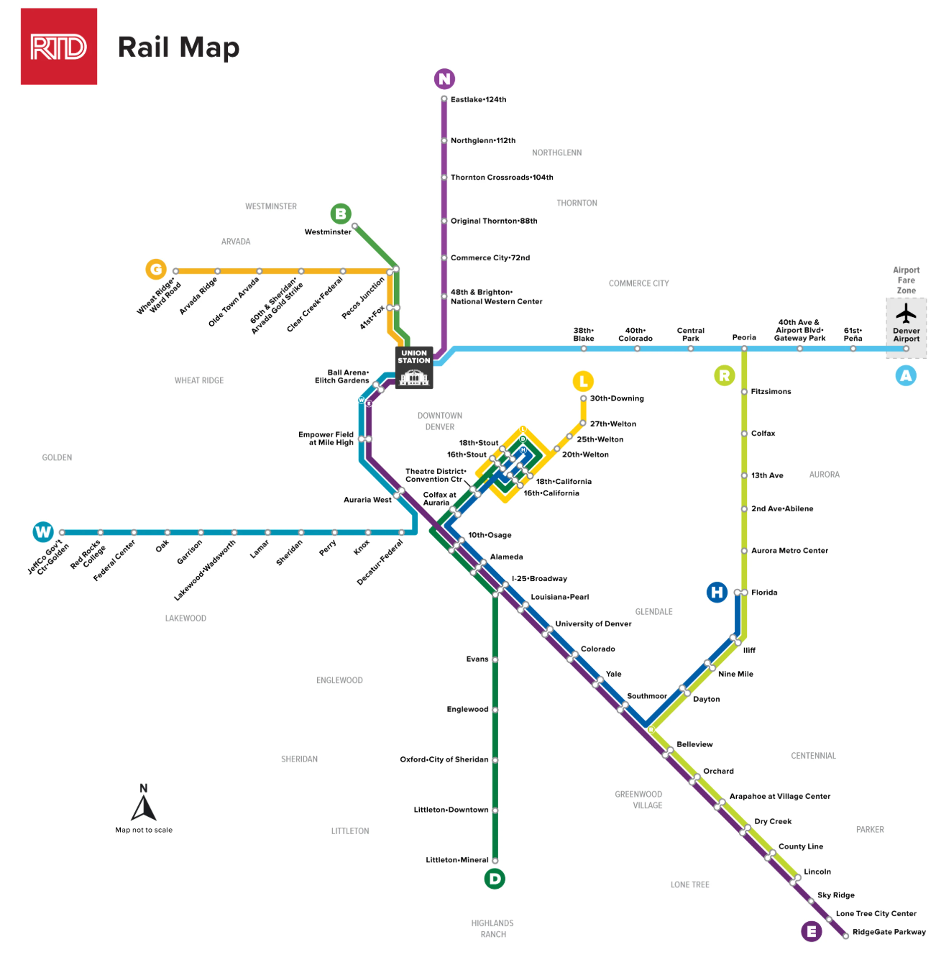

Denver’s RTD FasTracks program shows what happens when a city builds transit instead of endlessly studying and debating it. Since the mid-2000s, Denver has constructed multiple light rail lines radiating from downtown, including to the airport.

That investment is amplified by very solid bike infrastructure. Denver has built out protected bike lanes and trails that connect places people need to go. As I argued in “The Normie Case for E-Bikes”, the combination of bike infrastructure and the ascent of e-bikes means that the 45% of all trips that are four miles or less can become a lot more feasible to do without a car.

What’s important is that Denver actually built this infrastructure rather than getting paralyzed in planning. Many cities produce beautiful transit studies that never break ground. Denver got it done. They didn’t wait for perfection. They didn’t let every neighborhood group hold projects hostage. They didn’t spend years hiring consultant after consultant to produce plan after plan. They secured regional funding through RTD, picked routes, and built them.

The regional approach mattered a lot here. RTD operates across the metro area, not just Denver proper, which means the system serves where people live and work rather than stopping at arbitrary city boundaries. Metro areas that are split up between different cities with fragmented transit systems should study how Denver did this so well, because this regional approach makes the transit system much more useful for commuters instead of a downtown-only amenity.

The result in Denver’s case is a metro area where a family is able to choose one car instead of two and where some (depending on their situation) can go carless entirely. This matters because transportation costs are often a large share of household budgets. Between car payments, gas, insurance, and maintenance, the average American household spends over $10,000 annually on vehicle expenses. For middle-class families, that’s a significant portion of take-home pay going to simply getting around. Putting that money back into people’s pockets makes a real difference.

A Business-Friendly Approach

Colorado has adopted a much more market and business-friendly approach that many of its blue state counterparts. For example, according to the Cato Institute, Colorado rankssecond in the country for freedom in occupational licensing. The state has a4.4% corporate income tax (so it’s half of California’s 8.8% tax), which places it 11th lowest overall. It ranked11th in last year’s CNBC “Top States For Doing Business.” Of the states that voted for Harris, only Virginia ranked higher. The state’s Governor, Jared Polis, is an enthusiastic cutter of red tape; in a great bit of political theater, when he cut208 executive orders that were making government less efficient, he even literally cut through those orders with a table saw!

Denver Mayor Mike Johnston is only adding to this. Last year, his first executive order established a maximum permit review time of 180 days, created “project champions to expedite development applications, and explicitly adopted a “Get to Yes” focus. These kinds of initiatives mean that when a restaurant wants to open, or a tech company wants to expand, or a developer wants to build, the city works with them rather than against them. Regulations are clear, predictable, and reasonable. This approach generates economic dynamism. Businesses create jobs, pay taxes, activate street life, and provide the services residents need. An office building full of workers supports the lunch spots, coffee shops, and transit ridership that make a city function. A new Trader Joe’s makes it easy to walk to the grocery store. Growth creates opportunities for people to build careers and support families. The alternative (treating every business as a threat to be regulated into submission) produces stagnant cities where costs spiral because supply can’t keep up with demand.

Parks and Green Energy

Denver’s park system is genuinely excellent. These parks make neighborhoods more desirable, give families affordable nearby recreation options, and create the kind of public space that makes for a livable city. They also link up with and support the bike infrastructure that I mentioned earlier.

On energy, Colorado and Denver have been aggressive about shifting to renewables while keeping the system functional and affordable. Xcel Energy, the main utility, has rapidly expanded wind and solar capacity without rate spikes or reliability problems. This matters because it shows that the green energy transition is achievable without making energy unaffordable or forcing people to sacrifice comfort.

Rather than telling people to use less energy or accept higher costs in the name of climate goals, Denver focused on actually building renewable generation capacity. More solar farms, more wind turbines, better transmission, it’s supply-side solutions that let people live their lives for cheaper while reducing emissions.

The Virtuous Cycle

This is the payoff of getting the fundamentals right. When you allow housing growth and business development, you generate the tax revenue for social services and great parks. When you don’t let NIMBYs block everything, you can actually build solar energy and bike infrastructure. When you maintain a functional economy, you can invest in public amenities that improve quality of life. Denver created a virtuous cycle; it’s a recipe for other blue cities to follow.

-GW