The Newest Argument for Price Controls is Still Wrong

A New Twist on a Misguided Idea

After this latest round of elections in New York, New Jersey, and Virginia, Bharat Ramamutri and Neale Mahoney have been arguing, most prominently in the New York Times this past Sunday, that policymakers, when faced with voter demands for immediate relief from high housing and utility costs, should embrace temporary price controls paired with long-term supply reforms. They acknowledge all the standard economic objections to rent caps and rate freezes (reduced investment, declining maintenance, market distortions, etc.) but argue that these costs are worth bearing because supply-oriented policies can’t work fast enough to help voters who want immediate relief.

The argument has a certain appeal. It sounds pragmatic, even sophisticated, and it acknowledges tradeoffs while trying to meet voters where they are. They get a few things right: affordability is a serious challenge for voters, and they do want help right now. The problem is that the rest of their argument rests on three faulty assertions.

1) Politically bundling price controls with supply expansion is unlikely to work as advertised

Perhaps the most novel claim in Ramamutri and Mahoney’s piece is that price controls can actually enable supply reforms politically.

The logic is that rent caps or utility rate freezes provide immediate relief that buys political capital, which then allows politicians to pursue the harder work of zoning reform and permitting streamlining. They cite Rogé Karma’s Atlantic piece suggesting rent control has been essential to making way for some development-friendly reforms. It’s an elegant theory. It’s also contradicted by virtually all available evidence. We have decades of experience with rent control cities, and the track record is unambiguous: strong rent control does not lead to strong supply growth. In fact, it appears to do the opposite.

San Francisco has had robust rent control since 1979; that’s 46 years to build a pro-supply coalition, and still San Francisco is nationally notorious for blocking housing development. Instead of a rent-control plus more supply politics you got a place with battles over every proposed apartment building, endless environmental reviews weaponized against housing, and neighborhood groups that fight projects with the intensity of a religious crusade.

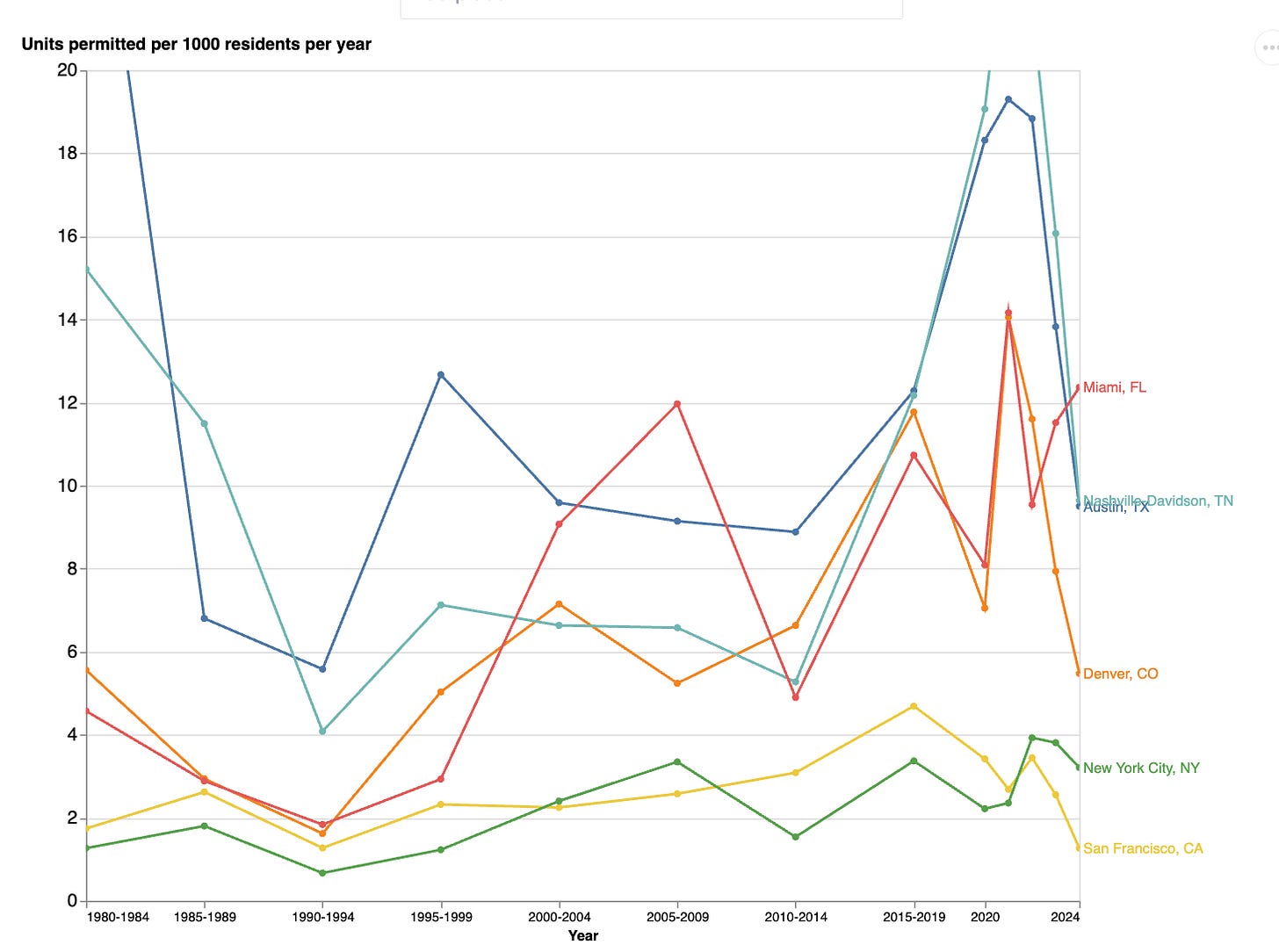

New York isn’t that different. It has the most extensive rent stabilization regime in the country, with almost half of the city’s apartment rent-stabilized. That regime is an inheritance from World War II-era emergency measures. Eighty-plus years should be plenty of time for rent control to enable supply reforms, right? And yet New York remains one of the most difficult places in America to build new housing, with a Byzantine approval process and vocal opposition to development. And, as you can see San Francisco and New York consistently don’t build as much as housing as other cities in the country. The takeaway is that rent control doesn’t lead to supply expansion.

Los Angeles expanded rent control in 2019 (and then added to this just last week) while simultaneously enacting some of the nation’s most restrictive tenant protection laws. Has this created political space for abundant new construction? The city is building at a fraction of what it needs, and the politics remain dominated by fights over limiting development, not enabling it.

Cities with rent control tend to have slower housing growth than cities without it. This directly contradicts what Ramamutri and Mahoney predict rent control will lead to.

You can apply the same concept to how we view energy supply and caps. States that have implemented electricity price caps haven’t suddenly become champions of streamlined energy infrastructure. And in fact, by cutting into utilities revenue, they can delay infrastructure upgrades and reduce grid reliability.

2) “Temporary” price controls tend not to stay temporary

Ramamurti and Mahoney acknowledge a major problem with their proposal: “price caps tend to stick.” They recognize that once price controls are enacted, interest groups mobilize to preserve them, beneficiaries argue for expansions on fairness grounds, and the political cost of letting controls expire becomes prohibitive. But having acknowledged this reality, they proceed to wave it away with sunset clauses and assurances about “specific timelines.” This is wishful thinking masquerading as policy design.

Once you implement rent control, you create a class of beneficiaries who will fight ferociously to preserve it. A tenant paying $2,000 for an apartment that would rent for $3,500 on the open market has captured $1,500 per month in value. That’s real money. It is the perfect example of golden handcuffs. Of course they’ll organize to keep it. Of course they’ll show up at city council meetings. Of course they’ll donate to politicians who promise to maintain and expand protections.

Politicians understand this dynamic perfectly well, which is why sunset clauses are essentially meaningless. Imagine you’re a city council member and the sunset date arrives. You have a choice: let rent control expire, which means thousands of your constituents will see immediate rent increases, or extend it for another few years. The political calculation isn’t complicated. The tenants who benefit from rent control will punish you at the ballot box for letting it expire. The diffuse future benefits of increased housing supply won’t materialize for years and can’t easily be attributed to your vote anyway. So you extend it. And then, when that extension expires, you extend it again. And again.

3) The supply-side reforms they treat as hopelessly slow can be implemented quickly if we have the political will to do so

Ramamurti and Mahoney frame their argument around a core premise: supply-side solutions take years, voters need relief now, therefore we need price controls as a bridge. But this premise is wrong. The vast majority of regulatory reforms that would unlock housing and energy supply can be implemented quickly.

When Minneapolis ended its parking minimums in January 2020, the city immediately saw a surge in housing production on small lots that had been unprofitable to develop under the old requirements. When they allowed larger apartment buildings along commercial corridors in 2021, they got another development boom. These weren’t decade-long processes. They were policy changes that enabled construction within months.

Suburban towns that want to be more affordable for the cops, nurses, and firefighters their communities depend on can immediately allow duplexes and triplexes on single-family lots. Cities can allow residential development by-right in commercially zoned areas (as I argued for two weeks ago). If you make Accessory Dwelling Units (ADUs) legal and eliminate discretionary review (so that developers can build housing based on a predictable and clear set of rules rather than the whim of a review board), property owners can start building them within months. These reforms don’t require new infrastructure or major construction projects. They just require burdensome regulations getting out of the way.

Ramamurti and Mahoney are right that voters want immediate relief. They’re wrong that this demands price controls. What it demands is implementing the fastest supply reforms possible and communicating them effectively. When you tell voters “we’re legalizing apartments above shops and stores throughout the city, developers can start building within 60 days,” that’s immediate action. When you tell them “we’re eliminating parking requirements that make housing expensive and we’re seeing new projects proposed already,” that’s visible relief. When you show that Minneapolis implemented zoning reform and immediately saw more housing construction, that’s proof it works.

The same holds for energy. Streamlined interconnection is immediate relief for renewable projects ready to go. Eliminating unnecessary transmission permitting delays is immediate relief for grid capacity. Allowing distributed generation is immediate relief for electricity supply. These aren’t decade-long processes. They’re policy changes that can happen fast if we prioritize them. The choice isn’t between price controls now and supply eventually. It’s between policies that relieve shortages and policies that try to redistribute their way out of them. Supply reforms can work on timeframes that voters care about. We just need to implement them, and make that known to voters!

-GW

My default position is also that rent controls are stupid and counterproductive. But this post seems to miss or overlook some things.

In part one, you seem to make a bit of an ad-hoc error. Or, at the very least, fail to link two things that are happening. Is there an actual reason why rent controls make it harder to do supply-side reforms? I am not an expert, so the answer might be "yes." But that's kinda the key to making this point.

The rent-control proponents you are rebutting are saying that we SHOULD do supply-side reforms with rent control. So unless doing so is reasonably impossible, rather than just not previously concurrent, all you are saying is "My opponent is wrong because if we do not do their plan...their plan will not work!" ...no duh.

The second portion fixes this issue: there is a direct tie between "they propose X...here's why it won't happen that way."

The other issue I have is one I have had with people discussing this affordability topic for a while now. What should politicians do if what voters want is impossible?

Voters actually want lower nominal prices. Cool, let's engineer a financial catastrophe, I am sure that will make them happy!

Ok, let's compromise and negotiate them back into improvements in real prices instead! Well, that's been happening for years now and people are still very mad.

I suppose "More of a good thing that's already happening!" is a fair enough desire for voters, but at some point it becomes unreasonable or impossible. Imagine if voters were FURIOUS every quarter there wasn't 10% GDP growth (extreme and silly, but makes the point).

Yes, Trump could drop the tariff nonsense and that would provide some improvements along this axis. We could do all the things you mention in part three of this post and that would show progress more quickly than many thing. But I am skeptical it would be big enough fast enough.

The US is many millions of homes "behind" demand. Even with optimal reforms happening immediately everywhere (not a thing that's feasible even if desirable) there is still going to be a while before the kinda of price relief people say they want.

And that ignores the fact that the people who want price relief getting what they want is directly in opposition to the ~70% of Americans who own homes and would be made poorer by the success of the home-wanters. This is not a defense of NIMBYism, just a complicating fact.