How to Take Mixed-Use Zoning From Cool Concept to Reality

It’s Residential in Commercial

If you’ve been to Europe and really liked it, there’s a good chance that one thing you really liked without realizing it is mixed-use zoning. In Europe, land-use regulation is mixed use by default. There’s housing so that people can live. There are amenities so that people can shop, eat, and recreate. There are businesses so that people can work. And they are right next to each other and mixed amongst each other. That creates vibrancy, shorter and more pleasant commutes, and more economic activity.

This is the core of the magic of New York City. To a greater extent than anywhere else in America, NYC does this. And it’s a big part of why so many people are willing to pay such a premium to live there.

Unfortunately, outside of New York City and a few especially tony parts of a couple of other major cities, we largely don’t do that in the United States. Here, walkable, mixed-use, reasonably dense development is essentially illegal in most of America’s zoning codes. That’s a real shame because mixed-use zoning has a wide range of benefits.

Renters and first-time homebuyers benefit from the increase in housing supply. There is huge potential for more supply here. According to the Lincoln Institute for Land Policy, if we redevelop just 20 percent of the country’s underutilized commercial corridors to mixed-use sites with ten housing units per acre, we could add more than one million homes. It’s good for workers who can live closer to their jobs and thus enjoy shorter, less stressful commutes. It’s good for businesses who benefit from increased foot traffic. It benefits seniors who can maintain independence longer in a walkable environment. And it saves money for taxpayers because it requires less infrastructure investment since the same roads, sewers, and utilities, etc. serve multiple uses at once, which reduces long-term maintenance costs.

That’s a long list of winners from having more mixed-use zoning. With fewer restrictive zoning regulations that allow for more mixed-use development, private sector developers will gladly create a greater supply of these kinds of areas to meet that demand. A city that leans into capitalism is thus a city that will de facto be leaning into this kind of very attractive mixed-use development.

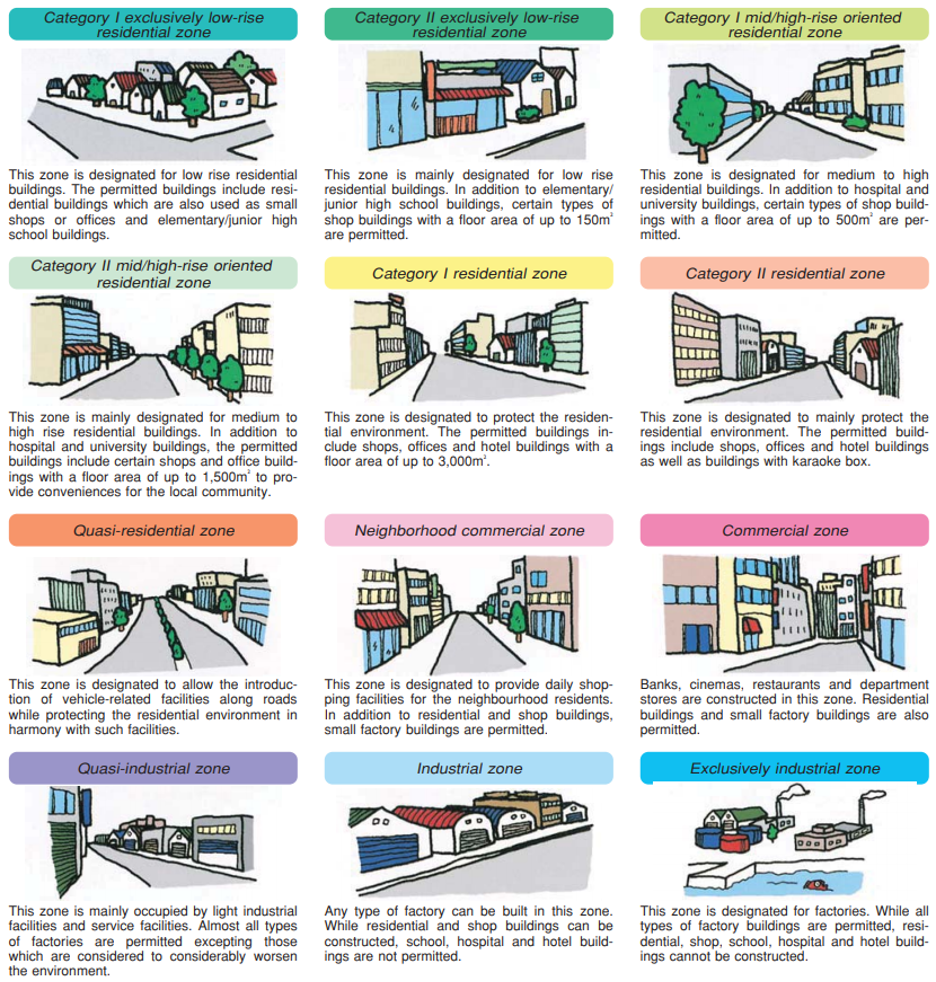

There’s also a lot that we can learn from other countries. The liberal, nationally determined nature of Japanese zoning is particularly effective compared to what we do in America.

Likewise, Matt Yglesias points out that: “One of Italy’s real strengths seems to be a lot less fussiness about the idea that everything needs to be in the right little box. Every Italian community I saw contains a mix of detached houses, townhouses, and apartments. Every Italian community I saw contains a blend of old and new structures.”

Why Residential in Commercial is the Way to Go

Many people want to live in suburbs. That’s totally fine and normal. I live in a suburban neighborhood and love it. But many others want to live in these kinds of mixed-use spaces. 60% of Houston residents for example say that they would like to live in a mixed-use development. Capitalist developers should be allowed to build to meet that demand. So then how do you improve your regulations to actually let them do that?

A good starting point is to make it easier to add housing in areas that are currently zoned as commercial. This kind of regulatory reform polls well. 75% of respondents support allowing more apartments to be built near offices, stores, and restaurants. People like being able to live, work, and play conveniently close to each other, with their housing being affordable, their commute being short, and fun amenities they enjoy being nearby. Importantly, because the area is already zoned as commercial, developers are less likely to run into NIMBY opposition there than elsewhere. (Sometimes NIMBYs will just have to be straight-up defeated politically but it isn’t the worst thing for us YIMBYs to sidestep their opposition when we can).

How to Do Residential in Commercial Right

The key to making this work isn’t complicated: get out of the way and let developers build. That means eliminating the procedural barriers and arbitrary restrictions that currently make these projects difficult or impossible. Three reforms in particular would unlock much greater mixed-use development.

First, residential development should be allowed by-right in commercial zones. No rezoning. No special exceptions. No variances. No conditional use permits. None of it. If a site is already zoned for commercial use and has basic infrastructure like water and sewer connections and it’s all up to fire code and safety regulations, housing should simply be permitted. This is the single most important reform because it eliminates the discretionary gauntlet that kills most projects before they start. Under current rules, even when a developer wants to build exactly what a city claims to want (more housing in walkable, transit-served areas), they often face months or years of costly uncertainty navigating a politicized approval process. By-right development would dramatically reduce risk and make projects financially viable.

Second, cities need to allow meaningful density and height. It makes no sense to finally allow housing in commercial zones only to cap it at such low densities and heights that nothing actually gets built. The standards should be reasonably generous: at a minimum, these projects should be allowed to match the highest residential density permitted elsewhere in the city. If a municipality allows 50 units per acre somewhere else, it should allow in places that are currently zoned as commercial. The same logic applies to height. Projects should be able to match the tallest buildings allowed within a half-mile or one-mile radius. These areas already have the infrastructure, the commercial activity, and often the transit access that you need to support housing. Artificially constraining how much housing can be built there is wasting a good opportunity.

Third, approvals need to be genuinely streamlined, not pseudo-streamlined in name only. That means hard deadlines: 60 days for smaller projects, 90 days for larger ones. And crucially, automatic approval if cities miss those deadlines. Without real consequences for delay, “streamlined review” becomes meaningless. Cities will always find reasons to drag things out, whether through requests for additional studies, multiple rounds of revisions, or the endless design review sessions that substitute aesthetic preferences for actual standards. Automatic approval provisions give cities an incentive to move quickly and give developers certainty about timelines. That certainty is valuable: it means construction loans make sense, investors can commit capital, and projects actually happen instead of dying in limbo.

These three reforms:

-by-right approval,

-reasonable density and height allowances, and

-genuinely fast permitting

would transform residential-in-commercial from an interesting concept into a powerful tool for adding housing supply. The beauty is that none of this requires new subsidies or government spending. It just requires cities to stop blocking what the market already wants to build.

A Better Approach Than Rent Control

When cities look around and see that ‘the rent is too damn high’, the political economy temptation is to reach for a price control. It’s intuitive, it feels like you’re helping renters immediately, and it polls well. But rent control doesn’t actually solve the underlying problem, it just redistributes scarcity in the short term while making it worse over time. Study after study shows that rent control reduces housing supply, decreases maintenance, and makes it harder for people to move into the area.

Residential-in-commercial zoning reform offers a much better approach. Instead of fighting over how to divide up an inadequate supply of housing, it increases supply. More housing means more competition between landlords, which naturally puts downward pressure on rents without any of the distortions that rent control creates. And unlike rent control, which unfairly benefits current tenants at the expense of people who want to move into the area, increasing supply helps everyone in the market.

The political appeal of residential-in-commercial makes sense too. It’s about allowing development where it already makes sense, i.e. in areas that are already built up, already have infrastructure, and where neighbors are less likely to object because it’s not changing the character of residential neighborhoods. You’re not asking anyone to sacrifice. You’re just letting the market meet demand in places where that demand already exists.

Price controls feel good but they aren’t the long term solution. Cities serious about housing affordability should focus their energy here rather than on rent control. Enable more building in commercial zones, streamline approvals, don’t spike the development with overly restrictive density and height limits, and let developers respond to demand. That’s how you actually make sure that the rent stops being too damn high.

-GW

Amen! What are the political obstacles preventing this, if you say, 75 percent support mixed use? Everyone visits Europe and says "why don't we build like that here" and yet we never do!