When the American Dream Stops Moving

The Great Freeze in Labor and Housing Mobility

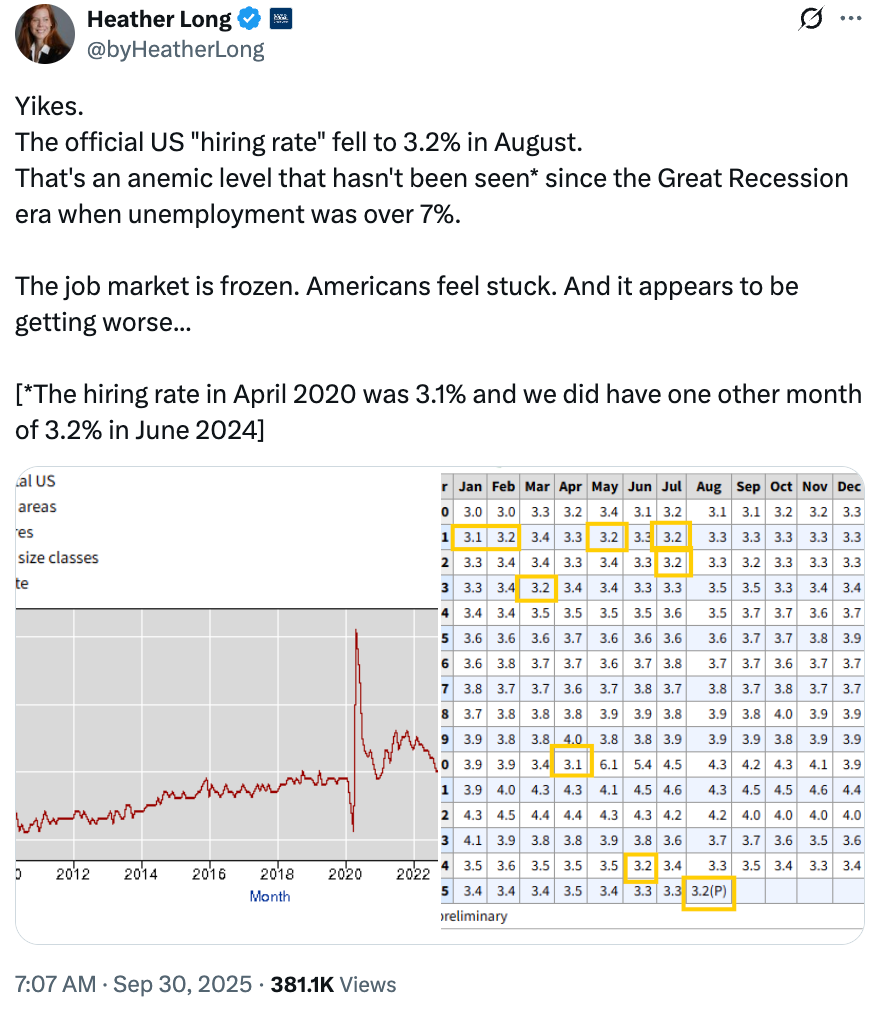

American workers are switching jobs at a glacial pace. The U.S. hiring rate stood at just 3.2% in August 2025 – meaning only about 3 out of 100 jobs were filled that month. Outside of the 2020 pandemic shock, that matches the lowest hiring churn in a decade. By comparison, in the late 2010s the hires rate hovered closer to 4%, so this represents a steep drop in labor market dynamism. Confirming the freeze, the quits rate – a proxy for workers’ confidence to voluntarily change jobs – ticked down to 1.9% in August, a level not seen since 2020. In short, fewer people are taking new jobs and even fewer are leaving their current ones, signaling a workforce that has collectively hit the brakes on mobility.

Such labor market stagnation has been building over the past year. There were still about 7.2 million job openings in August (plenty of vacancies), yet hiring and quitting remain subdued. Economists have dubbed this a “low-hiring, low-churn” environment – essentially a great freeze in labor mobility. Layoff rates are historically low as well (around 1.1%hiringlab.org), which on the surface sounds like good news for job stability.. A stagnant labor market may look calm, but it masks a lack of dynamism. In healthy times, Americans changing jobs frequently – or “churn” – is vital for economic vitality. Workers quit to seek better pay or a better fit, and that movement pushes employers to compete for talent, raising wages and productivity. Fresh hires bring fresh ideas. Without turnover, companies risk stagnation in ideas and efficiency. Today, that churn engine is sputtering. The post-pandemic “Great Resignation” has given way to what we might call a Great Freeze of the workforce.

What’s causing workers to stay put? Caution and uncertainty loom large. After several interest rate hikes and recession alarms, many employees seem hesitant to risk a job move. Wage growth has also cooled, reducing the incentive to jump ship since a new job might not offer a big pay bump. Layered on top is another seizing force: tariff-induced policy uncertainty. Many firms are holding off on hiring and capital expansion plans because they don’t know what trade policy will look like six or twelve months from now. In a recent survey, 40% of business executives said they’ll scale back hiring in the coming half year due to policy uncertainty, and tariffs topped the list of worries over regulation, taxation, or monetary policy. For small and midsize firms heavily tied to imports, uncertainty over tariffs is already viewed as directly affecting headcount decisions and operations. In fact, NFIB data shows that many small businesses are pausing hiring amid this tariff confusion. The result is an uneasy equilibrium: Americans feel “stuck” in their jobs, as one economist put it. Indeed, Heather Long of Navy Federal Credit Union described today’s labor market bluntly: “Americans feel stuck. And it appears to be getting worse…”

Her words underline how closely jobs and housing aspirations are intertwined in the American Dream – and how both are now under strain.

The death of mobility is a policy choice, so we must start with reforming policy to fix it.

Housing Lock-In and the Drop in Mobility

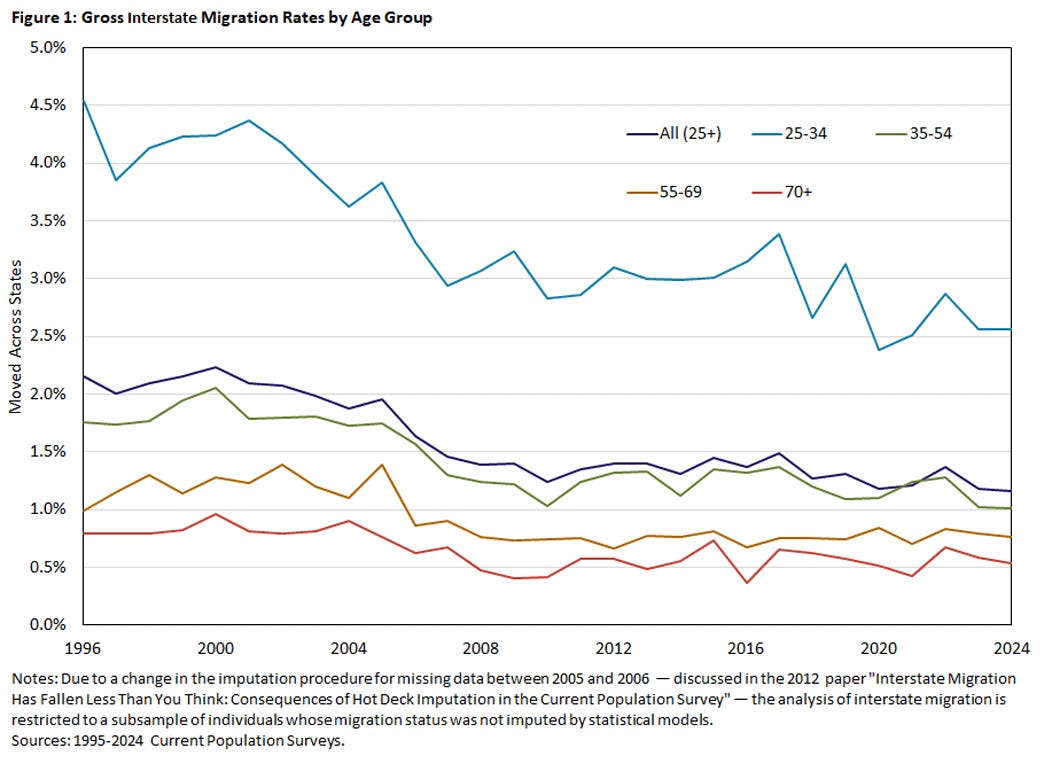

The paralysis isn’t only in the job market – it’s also at our front doors. Americans have stopped moving houses at rates unseen in modern history. In 2021, only about 8.4% of Americans changed residence, the lowest share since tracking began in 1947. For three years running, mobility has remained below 10% of the population – whereas post-World War II rates were twice as high, around 20% moving annually. The U.S. has become a nation of stayers.

One major factor is the frozen housing market. Home sales have plummeted amid a confluence of high costs and hesitant sellers. In August 2025, existing home sales were running at a 4.0 million annual pace – roughly 40% below the frenetic rate of 2021, and near the slowest pace since the 2008–2010 housing bust. Home sales have been sluggish over the past few years due to elevated mortgage rates and limited inventory, according to the National Association of Realtors. The data backs that up: the inventory of homes for sale is stuck at about 1.53 million units nationwide (just 4.6 months’ supply), far below what a healthy, balanced market needs. In many neighborhoods, “For Sale” signs are scarcer than ever.

Mortgage rates are the key culprit. After a decade of ultra-cheap money, the spike to ~7% mortgage interest has created a profound “lock-in” effect. Millions of homeowners are locked in 30-year loans during 2020–21 at rates near 3%. Now those owners are extremely reluctant to sell – doing so would mean taking out a new mortgage at double the interest rate, translating to hundreds or thousands more in monthly payments. As a result, would-be sellers are staying put, choking off the supply of homes on the market. Recent data shows over 70% of outstanding mortgages carry interest rates below 5%, a huge share of homeowners effectively handcuffed to their low-rate loans. This has “hindered total inventory recovery” by keeping many sellers on the sidelines.

The geography of mobility has also shifted. In the early pandemic, we saw some flight from high-cost coastal cities to more affordable regions. Indeed, California, New York, and Illinois experienced the largest net population outflows in 2022, while states in the South and Mountain West (think Texas, Florida) gained from inbound moves. But those dramatic pandemic moves have subsided, and a new reality has set in: even within metro areas, people aren’t moving like they used to. Local mobility has collapsed. The share of households moving within the same county fell from 8.3% in 2010 to just 4.8% in 2022 – essentially halving in a decade. High-cost metro areas exemplify this immobility. Take San Francisco or Los Angeles: sky-high prices and rising mortgage rates have made upsizing or relocating nearly impossible for middle-class families. Many young renters who once might have bought homes there have decamped to cheaper pastures, yet existing homeowners in those cities aren’t selling either (because where would they go that they can afford?).

The upshot is a kind of regional gridlock: people who are in expensive cities can’t easily leave (golden handcuff mortgages, or simply unwilling to give up cultural amenities for cheaper areas), and people outside can’t easily move in due to cost barriers. Everyone stays put.

This housing lock-in feeds back into the job market stagnation. When people can’t move geographically, they may also forego career opportunities that require relocation. A manager in Ohio might hesitate to take a promotion in California if it means tripling their housing cost. Likewise, someone in New York with rent control isn’t going to risk moving for a new job in a pricier city. Housing immobility thus reinforces labor immobility: economic opportunity gets tied to location, and if you’re stuck in place, so are your job prospects.

The death of mobility is a policy choice, so we must start with reforming policy to fix it.

Implications of a Less Mobile America

Does it really matter if people aren’t moving as much? Yes – profoundly. America’s famed economic dynamism has always relied on the ability of people to “pick up and go” – to chase a new job, afford a bigger home, or reinvent themselves in a new place. The sharp decline in both labor and housing mobility carries several serious implications:

Strangling the Productivity Engine: When workers don’t switch jobs, they often miss out on raises (the biggest pay bumps often come from changing employers). Low churn means slower wage growth for individuals and less pressure on employers to innovate or boost productivity. New ideas circulate more slowly within and between firms. Over time, this can contribute to the kind of economic stagnation that is hard to reverse. As one analysis put it, the labor market’s “flows” – hires, quits, even layoffs – show “how alive the job market really is”. Right now, those vital signs are weak.

Opportunity Trapped by Geography: Declining mobility risks calcifying the regional economic divides in the country. In a mobile era, a worker in a struggling Rust Belt town could move to a booming Sunbelt city for a better job. Today that worker might feel stuck because they can’t sell their house or fear the rent on the coasts. Meanwhile, companies in high-growth hubs struggle to find workers locally but remote hires don’t fully replace a robust local labor pool. The matching of people to places suffers. Prosperous regions can’t easily attract new blood, and distressed regions hang onto people who have few local opportunities. Over time this could deepen regional inequalities – entrenching “winner-take-most” cities while others languish.

Housing Market Dysfunction: The housing lock-in creates a feedback loop of its own. With current homeowners refusing to budge, first-time buyers are shut out of homeownership because there are so few entry-level houses for sale. Even though demand for housing is high, transactions stagnate. Builders have tried to fill the gap with new construction (in fact, new homes now make up a larger share of homes for sale than usual), but building is constrained by labor and material costs – both respectively facing shortages and higher costs thanks to mass deportations and tariffs. If mobility remains low, the U.S. could face a long-term homeownership decline, with more people locked into renting or living with family. The social ripple effects are significant: low mobility can contribute to lower birth rates (people delay having kids if they can’t upgrade homes), altered retirement patterns, and community fraying as those who do want to move find they simply can’t.

As historian Yoni Appelbaum points out, the freedom to choose one’s community—rather than remain “stuck where [you] are born”—is a distinctly American innovation and a pillar of both our prosperity. When Americans could move easily, they didn’t just find new houses; they found new chances—better jobs, better schools, better matches between talent and place. That mobility helped define the country’s civic temperament and economic dynamism. We lost that edge, and we are living with the consequences. In the 1960s, roughly one in five Americans moved each year; by 2023 it was one in thirteen. Appelbaum calls this collapse in geographic churn “the single most important social change of the past half century,” with knock‑on effects for entrepreneurship, job switching, and social trust. If people can’t move across neighborhoods or metros to meet opportunity, opportunity calcifies—and so do politics.

So the policy test is simple: make moving, between jobs and between homes, possible again. That means adding abundant housing where the jobs are (unclog zoning, speed approvals, legalize more “missing‑middle” and multifamily near transit), lowering the transaction costs of relocating (portable benefits, interstate license reciprocity, relocation tax credits or grants), and reducing family anchors that keep people stuck (reliable childcare and school access that travels with the child). Markets can help, employers offering remote‑first or relocation stipends; builders delivering smaller, faster‑to‑permit units — but they can’t clear the bottlenecks themselves. That is where public sector’s role is important: to help restore the infrastructure of movement so that Americans can once again go where the opportunity is.