We Could’ve Had Fast Trains

We Broke Ground. Then We Broke Everything Else.

This past week, we scored a historic win in California with the passage of SB 79 and a bold pro-housing package. Celebrations are absolutely in order, it’s a huge step toward making our state more livable and equitable. But as we pop the champagne, I can’t help but think: let’s bring that same energy to our trains.

I spent last weekend riding the Amtrak Coast Starlight. It’s a beautiful train, the views are breathtaking, the kind of journey that reminds you how gorgeous this state is.

But also… it’s slow. Painfully slow. The trip itself is five hours from Los Angeles to San Luis Obispo, meaning a trip that is around 200 miles, going at the typical speed of 40 MPH. That might be fine for sightseeing, but as transportation policy? That’s a failure. We should be moving people, and the state, faster, cleaner, and smarter.

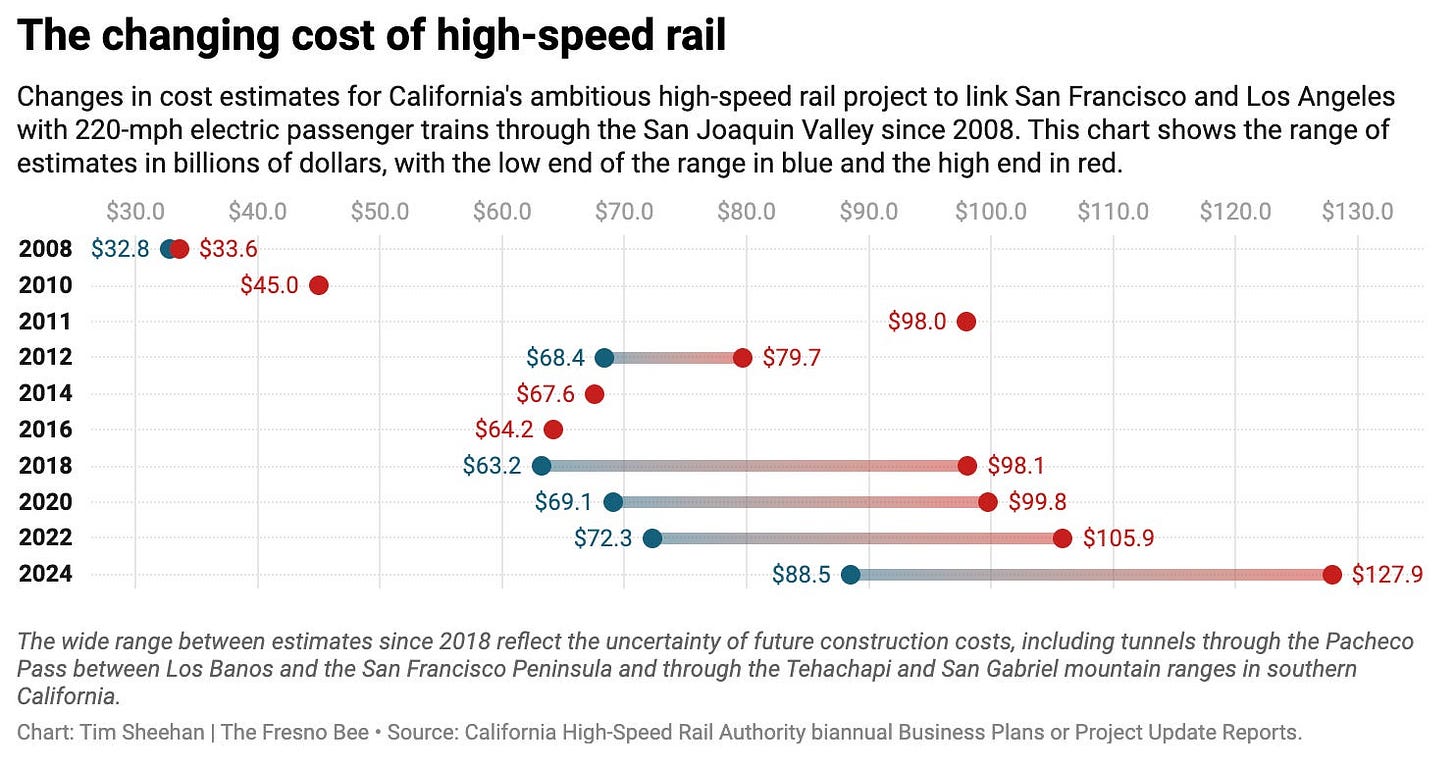

California’s long-promised high-speed rail (HSR) was supposed to fix that. Instead, it’s become a symbol of stalled ambition: billions spent, miles of rebar gleaming under the Valley sun, but no train yet in sight. The question is: is this a pipe dream, or a dream deferred worth fighting for?

We Politicized A Train (No seriously, we did.)

President Trump’s return to office in 2025 has once again put the project on the chopping block. His administration has moved to rescind $3.1 billion in federal rail grants previously awarded under the 2021 infrastructure law, aiming to reallocate the funds to “fiscally responsible” states. The California High-Speed Rail Authority quickly filed suit, echoing the bruising 2019 battle when Trump’s first term canceled a $929 million grant and threatened to claw back $2.5 billion more, an unprecedented strike against a state-led infrastructure project. Then, as now, California leaders blasted the move as a politically motivated assault on the nation’s only high-speed rail effort.

The partisan whiplash has become a defining feature of the project. With Trump back in the White House and a Republican Congress eager to brand the train a “boondoggle,” the project’s future again hangs by a thread. These swings in Washington have stretched timelines and inflated costs, proving that America’s infrastructure ambitions are hostage not just to engineering challenges but to political volatility.

Death by a Thousand Committees

But, the dysfunction plaguing California’s high-speed rail extends far beyond Washington’s failures. The state has engineered its own labyrinth of political compromises, legal constraints, and institutional conflicts, transforming what might have been a coherent infrastructure vision into a case study in how democracies can paralyze themselves.

As the New York Times reported, the project went through re-routing decisions that revealed how political expediency routinely trumped engineering logic. The detour through Palmdale added 41 miles and as much as $8 billion to accommodate a county supervisor’s district, while construction began not in the urban centers that would generate ridership, but in the Central Valley—politically safer terrain where land was cheaper and NIMBYism quieter. It all came from a backroom deal so that the same county supervisor could claim a win, along with Jerry Epstein — a member of the rail authority board and a developer who wanted a lease signed! The state chose to build the system’s least essential segment first, prioritizing a political deal over operational logic.

The gridlock worsened from California’s own regulatory infrastructure. The California Environmental Quality Act, has become one of the project’s most formidable adversaries. In Town of Atherton v. California High-Speed Rail Authority (2014), affluent Bay Area municipalities challenged the environmental review for the Peninsula corridor. The court’s ruling, while allowing construction to proceed, confirmed that even state-owned climate infrastructure must run the full CEQA gauntlet. The high-speed rail has faced dozens of such challenges—from Central Valley farmers worried about bisected farmland to Peninsula cities concerned about noise, from developers protecting planned communities to hospitals and churches demanding route changes.

The costs have been staggering. After releasing its environmental plan for the Bakersfield-to-Merced segment, the rail authority faced a cascade of lawsuits: Bakersfield sued over the downtown route; three separate farmer lawsuits in Madera and Merced counties resulted in $6 million in settlements and alternative route studies; Kings County extracted a $10 million payout to relocate a fire station; the town of Corcoran received $1 million for “aesthetic effects.” A developer sued claiming noise impacts. The City of Shafter demanded elevated tracks. Each settlement required design changes, legal fees, and critical time—during which costs continued climbing, and we have yet to see real progress.

The legal battles intersected with a more fundamental problem: institutional resistance from legacy infrastructure. In 2008, Union Pacific Railroad categorically refused to share its right-of-way with high-speed trains, citing expanding freight operations and safety concerns about mixing 200-mph passenger service with cargo traffic. This wasn’t mere obstruction, it reflected genuine operational constraints and liability fears. Yet it forced the state into costly land acquisitions, triggering new rounds of environmental review and litigation.

You can almost see the book “Abundance” write itself just from learning more about this! California didn’t merely fail to build a train line; it demonstrated how advanced democracies can become so procedurally elaborate, so legally contestable, and so politically fragmented that even broadly supported projects calcify into permanent works-in-progress.

If Other Countries Can, Why Can’t We?

While California has been struggling to lay its track, other countries have built thousands. Globally, high-speed rail is a proven mode of clean, efficient travel – but the United States is glaringly behind others. China is the most dramatic example: starting around the same time California approved its project, China embarked on an HSR building spree and now operates over 25,000 miles of high-speed railway (more than the rest of the world combined). China’s trains routinely exceed 200 mph, linking virtually every major city; by the end of 2020 China had 37,900 km (~23,500 miles) of HSR and is on track to hit 48,000 km by 2024 and 60,000 km by 2030. Crucially, this happened because the Chinese government treated rail infrastructure as a national priority – streamlining permitting, standardizing designs, and employing armies of engineers. The result is not only fast trains but also an economic catalyst: the flagship Beijing–Shanghai HSR line, for example, turned an operating profit of over $1 billion in 2015. China’s experience shows that scale and speed are achievable with unified political will and funding – though admittedly China’s centralized system is very different from California’s context of environmental reviews and private property rights.

Japan and Europe also offer instructive models. Japan’s Shinkansen, launched in 1964, was the world’s first high-speed rail. Japan has nearly 2,000 miles of high-speed lines in service today, and its networks boast enviable on-time performance and millions of riders. Japan’s model emphasizes meticulous maintenance and incremental upgrades – values California will need as it eventually operates its system. In Europe, countries like France and Spain have built extensive HSR networks at costs that often undercut U.S. projects. Europe collectively has about 7,700 miles of high-speed rail in operation (plus another 1,200 miles under construction) France’s TGV and Spain’s AVE lines were built faster and cheaper per mile than California’s, thanks to more standardized engineering and fewer bureaucratic delays. For instance, a European Court of Auditors study found the average time from planning to operation of an HSR line in Europe is around 16 years, even when extensive tunnels are involved – a timeline the California project has already far exceeded just to get partially operational. European rail builders also benefit from strong national rail companies (like SNCF in France or ADIF/Renfe in Spain) that carry in-house expertise, and from an ethos of “build it and they will ride” – sustained investment over decades to gradually expand the network. Not every European HSR line has met ridership hopes, and the EU has faced challenges integrating cross-border networks. But the core lesson is clear: clear governance has enabled other countries to deliver HSR as a nation-building project, whereas the U.S. approach has been piecemeal and hesitant.

To bridge the vast gap between California’s HSR vision and reality, policy makers at the state and federal level must enact common sense reforms. The status quo of drawn-out timelines and cost overruns is not inevitable – it’s a product of choices, processes, and governance that can be changed. Here are some reforms to consider, if we ever want this dream to become reality:

Streamline Permitting and Environmental Review: Complex environmental and permitting processes in the U.S. can slow major projects to a crawl. California has already begun to address this for housing (with new laws limiting CEQA delays) It should do the same for climate-critical transportation infrastructure. This could mean separating project planning from environmental review – thoroughly defining alignments and designs up front, then conducting a focused, faster review. Right now, reviews and route planning often happen in iterative loops that invite litigation and changes. By decoupling them, the High-Speed Rail Authority can lock in decisions earlier and avoid protracted fights over every mile. Streamlining should not mean ignoring environmental concerns, but rather handling them more efficiently – for example, using programmatic EIRs ( broad, high-level environmental review), limiting court injunctions to a set timeframe, and running state and federal reviews concurrently instead of back-to-back. Time is money: every year of delay adds inflationary cost. Faster approvals would save billions and deliver benefits sooner.

Secure Reliable Funding (State and Federal): This will be the hardest ask. After taking so long, California’s high-speed rail will need not just persistence, but major new funding. As former Transportation Secretary Pete Buttigieg said, “funding is the biggest barrier” to U.S. high-speed rail. California can’t build a $100+ billion system on hope alone.The state must find durable revenue—a new bond, dedicated funds, or private partnerships. Federally, a long-term rail fund like the Highway Trust Fund is essential. The 2021 infrastructure grants expire in 2026, and proposals for a $205 billion national investment need champions in Congress and Sacramento alike. Private investment should complement public dollars, as seen with the Brightline West project linking Las Vegas and Southern California. But, new funding will only come with trust. The rail authority must clearly show where each dollar goes and what it delivers to earn continued support.

Governance and Oversight Improvements: California’s high-speed rail project requires a complete overhaul of procurement and project management to avoid the costly change orders, contractor disputes, and coordination failures that have plagued it so far. The High-Speed Rail Authority must build robust internal expertise by recruiting experienced engineers and project managers—potentially from successful international programs like France’s SNCF or Japan’s JR—rather than relying heavily on outside consultants. This means implementing best practices such as design-build contracts to reduce handoff problems, breaking work into logically-sized contract packages, and prioritizing contractors’ proven delivery capabilities over just lowest cost. The state should also adopt risk-sharing mechanisms like delay penalties, streamline bureaucratic approvals through a more empowered delivery authority, and cultivate an organizational culture focused on on-time, on-budget delivery by learning from countries where rail projects succeed.

Learning from Success: Finally, California can take heart from smaller-scale successes. The state’s own Caltrain corridor on the San Francisco Peninsula is being electrified and will soon deploy high-speed-capable trains (though they’ll run at conventional speeds initially). Private ventures like Brightline in Florida have shown that Americans will ride trains if they are fast, frequent, and convenient. Brightline’s planned extension from Las Vegas to Southern California just received a $3 billion federal grant and broke ground with bipartisan support. This suggests that high-speed rail doesn’t have to be a partisan issue, if framed around jobs, mobility, and choice, it can attract broad backing. California’s HSR should be framed not as an exorbitant train for a few, but as a generational investment in clean transportation, economic development, and inter-city connectivity.

High-speed rail, despite its rocky start, still can hold the promise of convenient, zero-emission travel uniting California’s regions. The vision remains as compelling as ever: hop on a train in downtown Los Angeles and step off in downtown San Francisco a few hours later, having avoided airport hassles and highway traffic. As Quico Toro has recently noted, if we become a country that has been able to scale HSR across the nation, we can see spillover effects on other methods of transportation:

Once you have a high-performance, high-cadence, human-centered rail network at your disposal, life without it becomes inexplicable. In Japan, airlines are forced to compete with trains purely on price: the only way they can make up for air’s inherent inferiority in convenience, comfort and flexibility. Between Tokyo and Osaka, only time-rich/money-poor people choose to fly.

California’s bullet train might still be salvaged, but its real value may be as a warning—this is what happens when ambition meets dysfunction. If we want different results next time, we need different rules, reformed institutions, and different resolutions. Because accepting that America simply can’t build what other nations manage routinely is far costlier than any budget overrun. This can’t happen again.

How much of this is downstream of the governance structure of the state? You note a bunch of inefficiencies created by individual legislators wanting goodies for their districts. How do other countries that successfully build large-scale infrastructure avoid that problem? Who are the elected officials who ultimately oversee intercity rail transport in Japan and Europe, and to what electorates are they responsible?

What I'm trying to get at here is that maybe, for example, if CA had a legislature elected at least in part by statewide party-list proportional representation, you'd get more people in that legislature who consciously represented the common interests of the whole state and could help push through stuff like this. Or maybe we just need a voter initiative that creates yet another statewide separately elected commission (sigh) with independent approval authority over these things.

I don't know what the right structural solution here is. But I do think that the abundance movement has undervalued structural governance reform. It's all very well to say that law X or procedure Y could and should be much better... but how do you build the political coalition that provides stable support for those kind of reforms? Not an easy or simple question, ever, but I think we can say with confidence that "jawbone ordinary voters to think like rationalist technocrats overseeing the long-term interest of the state when voting for their local representatives" isn't going to cut it.

People forget that the reason China can get things built is because it’s an authoritarian country, where their government can simply order things to be built under penalty of prison or worse. So, using them as an example is kinda flawed.