There’s No Quick Trick to Solving the Housing Crisis

Why Banning RealPage and Airbnb Didn't Lower Rents

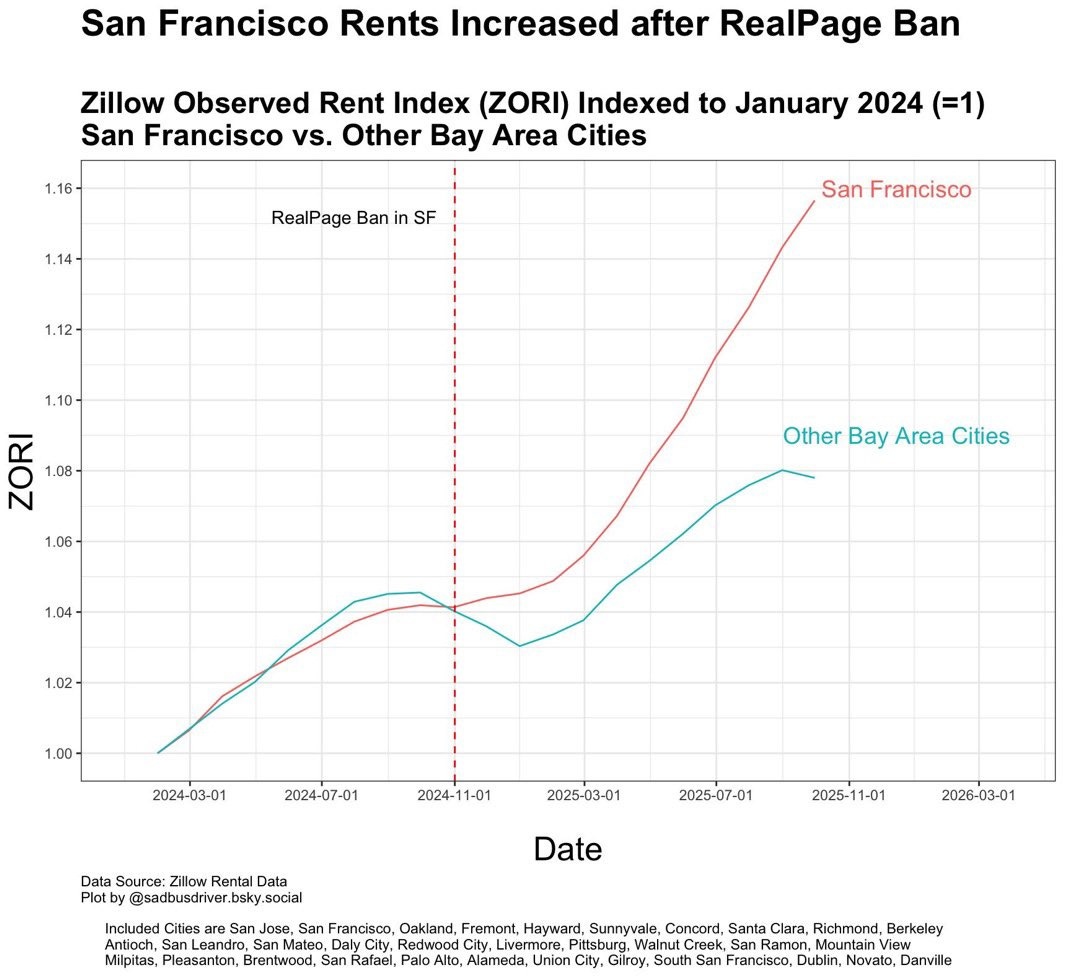

In 2024, San Francisco lawmakers set their sights on algorithmic rent-setting software, blaming it for collusive pricing and inflated rents. The city’s Board of Supervisors passed the nation’s first ban on the sale or use of such “algorithmic devices” for rent pricing. The ordinance asserted that these programs let residential landlords indirectly coordinate with one another – effectively colluding to raise rents, lower occupancy rates, and even keep units vacant to squeeze the market. As Supervisor Aaron Peskin put it, “RealPage has exacerbated our rent crisis and empowered corporate landlords to intentionally keep units vacant”. By outlawing software like RealPage’s YieldStar, officials hoped to remove those “coordinated” pricing signals and slow down rent hikes.

The hoped-for rent relief never materialized. In fact, San Francisco rents continued climbing after the ban. According to market data, city rents jumped by in the following year (roughly 9% increase). Apartments index showed the average San Francisco apartment rent reaching about $3,110 by mid-2025 – up from around $2,849 pre-ban. With San Francisco housing still nearly 154.6% more expensive than the national average. While correlation doesn’t always equal causation, the trend is hard to ignore: banning the pricing software did not stop rents from rising.

Image Credit: Joe Fish

Notably, one intended effect of the ban was to discourage landlords from holding units vacant for higher prices. While Peskin argued the software had “intentionally kept units vacant,” data on SF rental vacancy rates post-ban did not show a marked change (vacancy remained low, around 5% or less). If some landlords stopped using algorithmic pricing, they may have filled units a bit faster, but any increase in occupancy was not enough to soften rents citywide. RealPage’s compliance changes (removing non-public data inputs) may have reduced explicit rent coordination, but the market power of large landlords persisted. In essence, landlords continued to benefit from a very tight market.

In fact, the Department of Justice’s recent proposed settlement with RealPage further undercuts the alarmist narrative around rent-setting software. The DOJ chose not to dismantle RealPage’s services altogether. Instead, the proposed Final Judgment allows RealPage to continue offering pricing recommendations, so long as it does not use non-public data from unaffiliated competitors. That means RealPage can operate as long as it relies on public or internal data—confirming that the issue was never the mere presence of algorithms.

The DOJ’s willingness to settle rather than prosecute confirms a broader truth: the structure of the rental market—not just the tools—is the real issue. Algorithms may optimize pricing, but they don’t create scarcity. That comes from tight vacancy rates and a lack of new housing. The DOJ’s settlement reinforces what the data already showed: banning software tools didn’t lower rents. The problem is supply, not software.

If the goal was to break a pricing cartel, the symbolic victory might matter. But for renters looking for cheaper apartments, nothing changed. The ban didn’t produce a flood of available units or bring down asking prices.

A Ban That Benefited Hotels, Not Renters

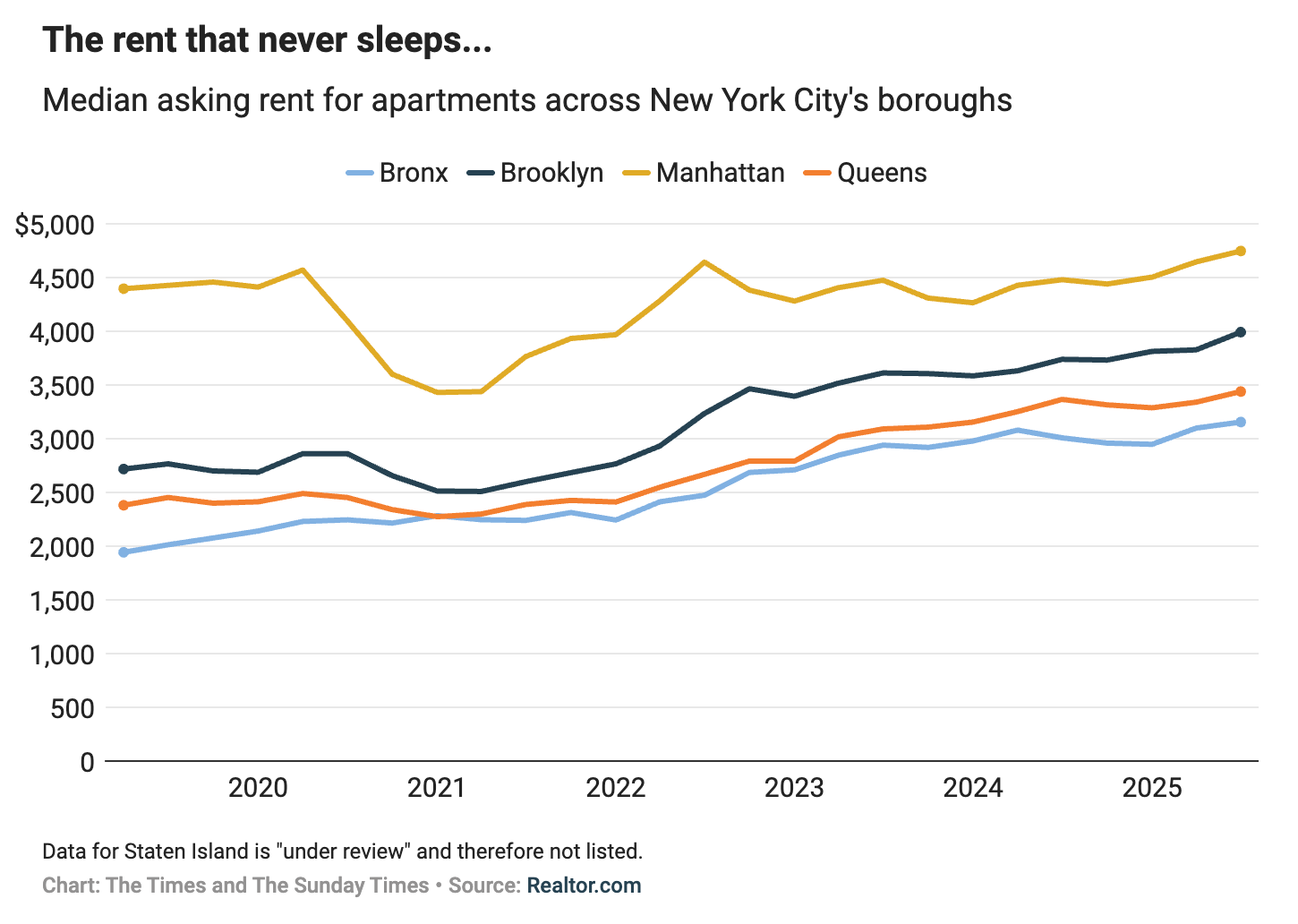

Across the country, New York City took its own swing at solving housing scarcity by cracking down on short-term rentals. Local Law 18, implemented in September 2023, banned most whole-home Airbnbs. Officials promised that removing tens of thousands of listings would return those units to the long-term market and ease rents.

That didn’t happen. By October 2025, Manhattan’s median rent reached a record $4,747/month, up 3.3% year-over-year. Brooklyn and Queens also saw increases.a healthy market.

Image Credit: The Times

While Airbnb listings plummeted (down 90%), the number of units converted to long-term rentals was negligible—just 1,400 out of more than 3 million housing units. And instead of renters benefitting, hotels did: average nightly rates surged to hitting $417, a night, this time last year. Hotel occupancy rates hit 91%, far above the national average.

It’s no coincidence hotels benefited so handsomely. The hotel lobby not only cheered the Airbnb ban – it has actively worked for years to constrain New York’s supply of accommodations. Long before LL18, the city’s politically powerful hotel workers’ union (the Hotel Trades Council, or HTC) pushed legislation to halt new hotel development. In late 2021, the City Council obliged, voting 46–1 to require a special permit for any new hotel citywide. This effectively killed as-of-right hotel construction. HTC’s president proudly declared the law “one of our most important long-term goals” to stop “unregulated hotel development” in NYC. The special permit rule forces would-be hotel builders through a gauntlet of public hearings and approvals – with union-friendly provisions baked in. New hotels must use unionized construction crews and commit to union labor agreements for operations, ensuring the union can veto or discourage projects that don’t meet its terms. In practice, very few new hotels get approved. By slamming the brakes on new supply, the hotel lobby protected its turf from both home-sharing and new competitors, which led to scarce rooms, sky-high occupancy and pricing power firmly in the hands of existing hotels.

The law removed an important income stream for thousands of middle-class New Yorkers, many of whom used Airbnb to make ends meet. Small businesses in Brooklyn and Queens also suffered, reporting steep drops in customer traffic now that tourists were pushed back into Manhattan hotel zones.

Villains Are Easier Than Solutions

There is no quick trick to solve a housing crisis. The pattern we see with RealPage and Airbnb bans reveals something deeper about how we approach policy: we’re often more comfortable identifying villains than confronting the structural scarcity that creates the problem in the first place.

When progressives fixate on algorithms or platforms as the source of high rents, they’re addressing symptoms while avoiding a harder truth, that we’ve systematically underbuilt housing for decades. This misplaced anger at other actors functions as a substitute for the political will needed to tackle root causes. Banning software or short-term rentals feels like doing something, but it doesn’t meaningfully add units to the market.

Real relief will come only from difficult but necessary reforms that increase the housing supply and expand capacity – from upzoning neighborhoods and streamlining permits to encouraging all types of new housing construction (and yes, even hotel development where needed). These measures lack the flashy appeal of a ban or a headline-grabbing crackdown, but they strike at the roots of the problem. Until our leaders muster the will to build our way out of the shortage, any supposed quick fixes will continue to disappoint. The housing crisis will not be solved by banning one thing or blaming one group; it will be solved by building, innovating, and making sustained policy changes that finally align our housing supply with the demand of a growing, dynamic city.

Great article and agreed

This is a great article. It's absolutely true that "villians are easier than solutions." But I also wonder whether naming villians -- not to divide or even to blame, but to gather receipts and identify where the bottlenecks really are (and who benefits most from them) -- is a necessary step on the way to solutions. (Worth noting that the "villians" used in the article's examples weren't the right ones... so not an effective strategy regardless and the article's points all stand!)