The Small Business Tsunami

Trump’s Tariffs Put Many of Them in a Dire Situation

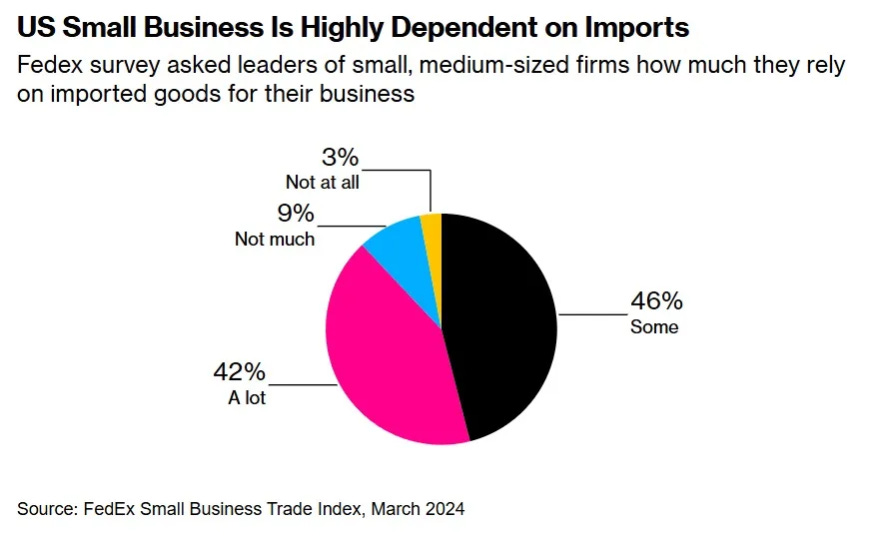

At a vibes level, many people associate globalization with large multinational corporations, but it is actually small businesses that are often the most dependent on international trade. 236,000 small businesses are importers, and they account for a third of all imports. Now that the majority of Trump’s tariffs are finally going into effect, those firms are going to face more than $200 billion in extra taxes. More than 40% of small businesses say they depend on imports a lot and only 12% say they rely on them not much or not at all.

This dynamic can surprise even some small business owners themselves. There was a widely shared video of a knifemaker who initially thought he would benefit from trade protectionism because he makes his product here in the United States; months later he came to realize that actually it hurts him because he needs to import steel and equipment.

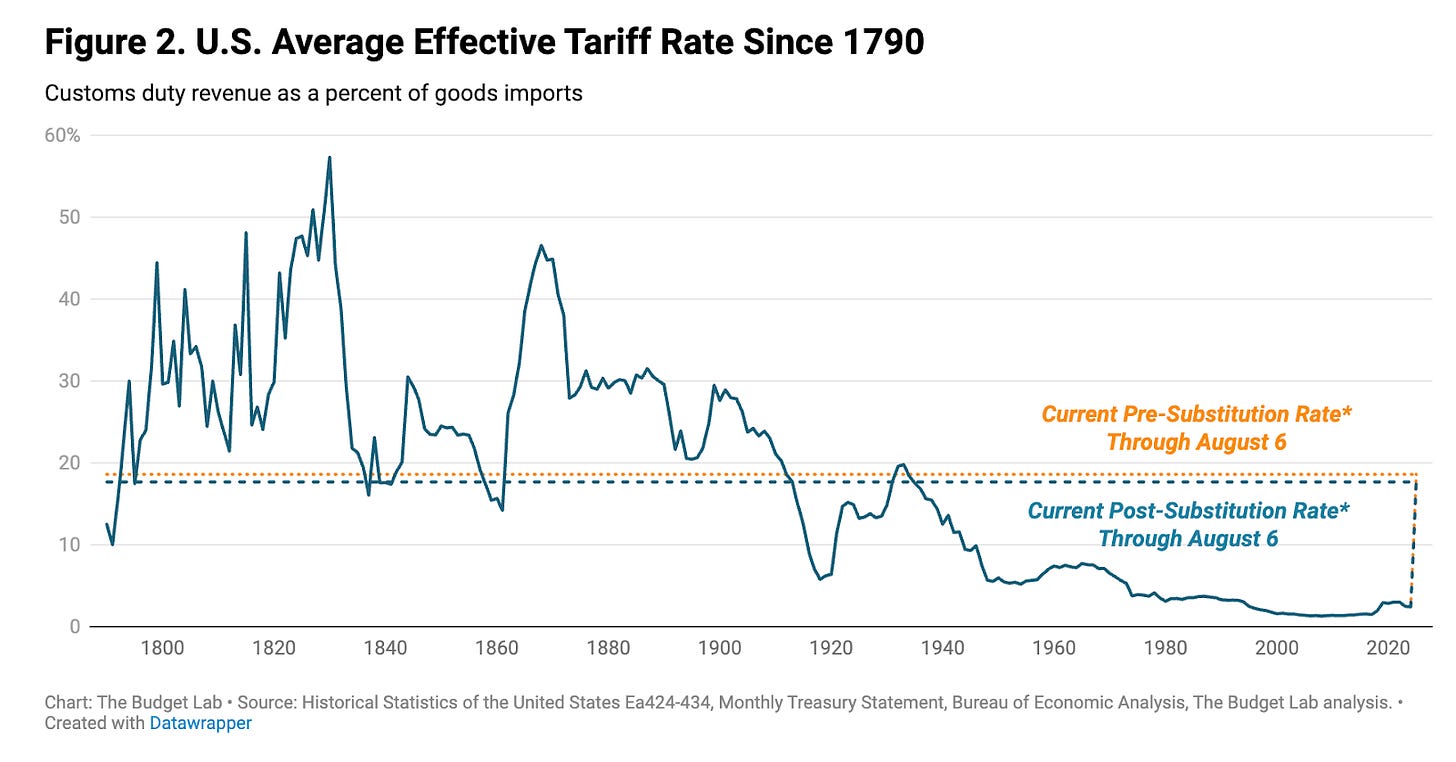

These tariffs have been in the news for months but they have gotten pushed back several times, which is where the TACO meme (Trump Always Chickens Out) came from, but those tariffs are mostly now coming into effect. On Monday, Trump put another 90-day pause on further tariff increases but the tariffs on China still stand at 30%. The 30% and 50% tariff on products from the EU and India respectively now apply. The de minimis rules that allow firms to skip tariffs entirely if their imports are under $800will go away on August 29th. All told, tariffs are now higher than they have been since the 1930s.

It has not yet entered mainstream public consciousness yet, but many small businesses face a cataclysm. This is going to be one of the dominant economic themes of the fall.

Why Small Business is Extra Vulnerable to Tariffs

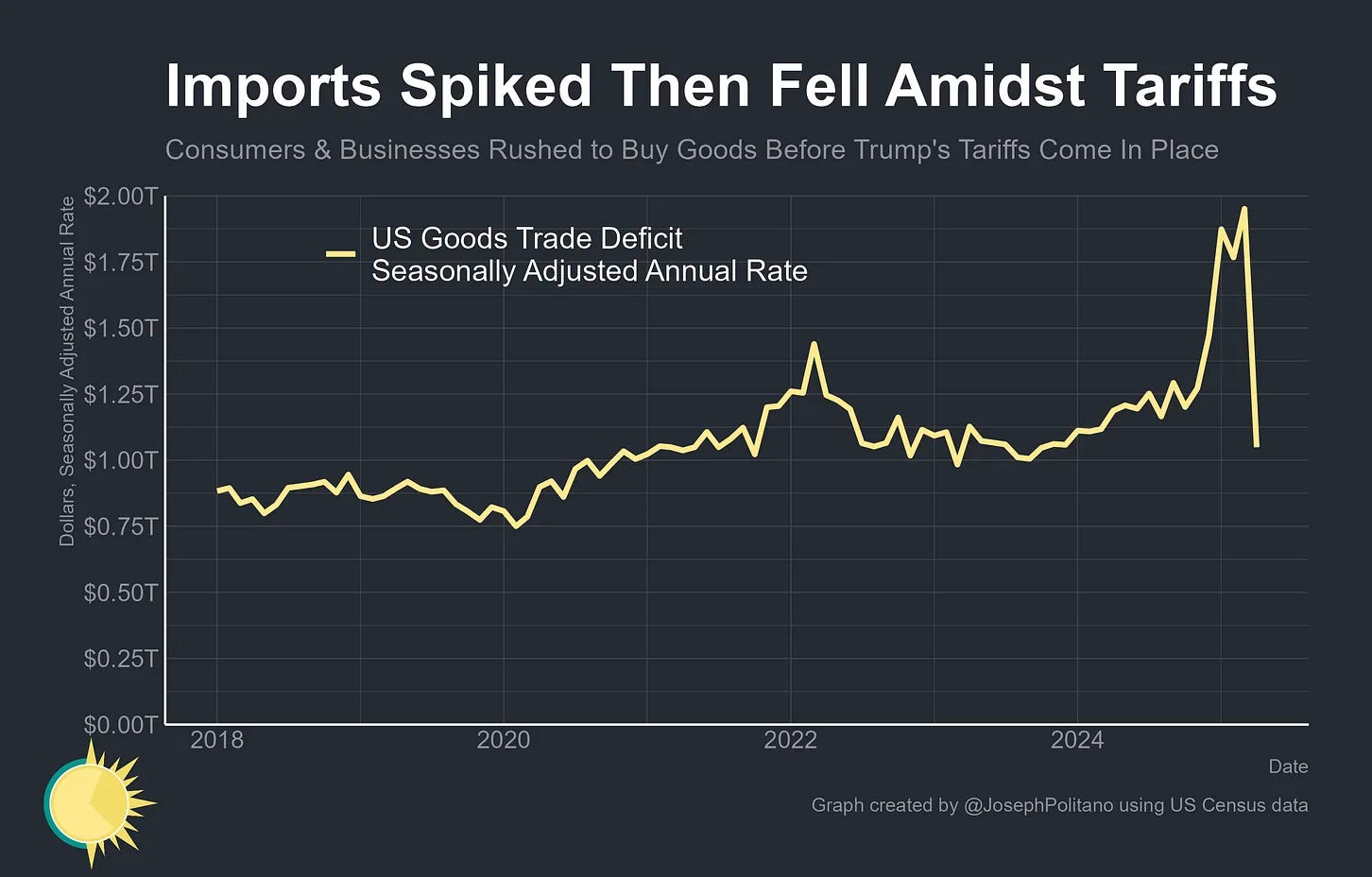

Small businesses have a much more limited ability to stockpile than big businesses. They simply don’t have the warehouse space, the money, or the logistical sophistication of larger firms. So while a larger business could build up a big inventory before the tariffs went into effect (andfirst quarter import data strongly suggests that they did that).

Smaller companies couldn’t do that nearly as much. This means they are going to rundown their pre-tariff inventories faster than their larger competitors.

Smaller firms also have limited bargaining leverage with suppliers. A large firm can look at its supplier and say “Hey, we’re facing these higher tariffs costs now and we need you to eat some of that cost or we’ll take our business elsewhere.” If that firm is a big enough customer for the supplier, they may be willing to do that rather than lose that big account. This does not typically happen for small businesses; they are price takers.

Due to the limited financial resources of small businesses, it reduces their ability to take short-term losses in hopes that Trump will just change his mind later. They have fewer supply chain options, rely more on de minimis exceptions, and can’t lobby for tariff exemptions like larger firms.

Small businesses typically export less, limiting their ability to shift from the U.S. as tariff costs rise; those that do export face retaliation, and the bureaucratic compliance costs of tariffs hit smaller purchases proportionally harder. And, because tariffs are not just a tax but are also a red-tape laden bureaucracy, the compliance costs of tariffs are proportionally higher for smaller purchases than larger ones.

What This Looks Like On the Ground

Smaller stockpiles are a real problem. Tooth Brigade, a small company that sells plush toys and books, was able to stock up enough inventory for the next few months, but not for the Christmas season. When they stock that inventory, they’ll have to pay 30% more for those items and that’s going to bite. As the owner says, “If our $16 plush suddenly costs more than $20, are consumers still going to buy it? We can’t pay for the increase ourselves, but we also don’t know if we can keep moving forward with our business.” Indeed, a huge range of Christmas goods being imported right now are being hit with these tariffs. The businesses are seeing the hit today; you’ll be seeing it in December.

Tariffs can be crushing. A company in Idaho with ~20 employees making tool belts. They needed to buy specialty magnets from abroad to make their tool belts. They got hit with a $78,000 tariff bill on top of the $50,000 cost of the magnets; the CEO said “We’re operating on razor-thin margins [so] it was existential.” The owners of a custom sheet-metal fabrication and machine shop have no idea how to make their operation work with 50% tariffs on steel and aluminum saying “I don’t know how to put a business plan together that makes any sense to anyone.”

The uncertainty isn’t helping small businesses either. As the President of a small gear business said last week, “We have precision gears on the ocean, coming from Italy, and I still don’t know whether I’ll have to pay a 15 percent tariff, or 27.5 percent. But either way, we have no choice: We’ll pay [for] it, and we’ll pass it on.”

Trump seems to love the special power that granting exemptions gives him. These deals are available to the biggest firms; smaller companies don’t have that as an option. On retaliation, to give just one example, Kentucky’s specialty bourbon producers and California’s small vineyards are getting hammered.

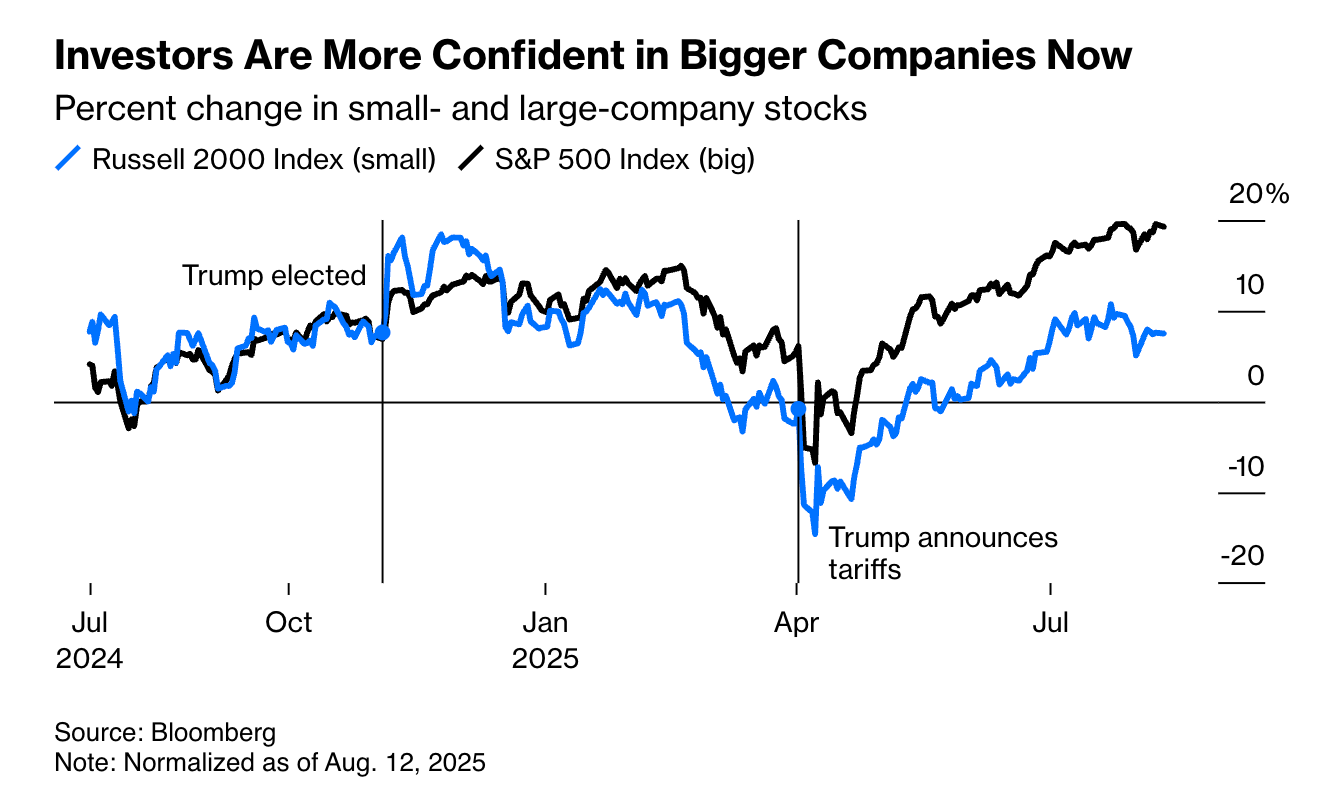

You can see how much all of these tariff headwinds are hurting small businesses in stocks. Typically, the stocks of large and small businesses move in tandem. This makes sense. After all, a good economy is good for business of all sizes, a bad economy the reverse. But look at what has happened this year. There’s been a notable and growing divergence between large businesses (which are in the S&P 500) and smaller businesses. The vulnerability to tariffs is a big part, arguably the biggest part of this.

This Hurts Consumers and Workers

Small businesses will tell you: “There is no “free tariff money” from foreigners. It comes from American businesses and creates nothing but bad options including: raising prices for our customers, laying off workers or cutting salaries and benefits, reducing investments, or taking high-interest loans. When even that is not enough, we will be forced to close.”

These firms tried to adopt a wait-and-see approach for a while but that is possible for only so long. A Seattle-based clothing company did that during the summer and kept prices the same for its fall clothing lineup, but they can’t afford to continue doing that indefinitely. They have already decided to raise their prices for next year’s clothes. The company will also be forced to let go of some of its 28 employees.

According to a recent analysis by Goldman Sachs, consumers were only paying about 22% of tariff costs through June with firms absorbing the rest but will end up paying about two-thirds of tariff costs.

It’s important to recognize that even though tariffs are on goods and not services, they bleed through to a lot of service-oriented small businesses too. That raises your costs, and does so in ways that most people don’t think about.Your favorite local coffee shop has to import its beans because, aside from a few small plots in Hawaii, coffee simply isn’t grown in the U.S. Coffee prices are up about 15% over last year and now sit at a record high price of $8.40/lb. That cost has to go somewhere. It either means a more expensive cup of coffee for you or it means less money to hire new workers for the business. Sometimes, both!

A lot of mechanics are small businesses and when your car needs a replacement part, the higher cost to them means a higher bill for you.This pass-through is why car insurance premiums are expected to rise 3% more over the next year than they would without Trump’s tariffs.

Small businesses are stuck between the hard walls of higher costs and price-sensitive consumers. It’s going to get bleak for many of them. As an open letter from the small business community argued “Waiting 6 or 12 months for a potential solution is not viable. Many of our businesses will no longer exist.”

Some businesses will just close or stop selling certain products. The U.S. franchise of Polarn O. Pyret, a company that makes durable waterproof outdoor clothes for children, couldn’t afford the tariffs and now has stopped importing new inventory. The owner called the situation “a little hamster wheel…. I’m constantly paying the tariffs and waiting for revenue to come in…. That just wasn’t a sustainable business model anymore.”

Once the current inventory runs out, parents won’t be able to buy those products at all. And of course, that owner and the people she employs won’t have jobs anymore either. A real win-win there.

What Democrats Can Do

This is what we’re staring at for the fall and winter and maybe further beyond: higher costs for many small businesses that force them to raise prices for consumers (if they can), employ fewer workers, and/or go out of business. The wave hasn’t crashed on our heads just yet, but it’s coming.

One silver lining is that this could give Democrats an opening to stand up for small business. We as a party need to be more business-friendly. This is a great opportunity to do that.

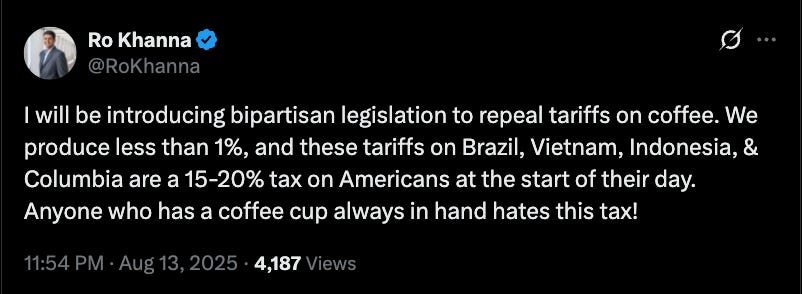

We need to keep our focus on the cost-of-living, continually highlight how it’s Trump’s policies that are causing so much economic pain, and commit to voters to fighting Trump’s tariffs as hard as possible if we’re able to retake control of Congress in the midterms. Another avenue is to present legislation to repeal tariffs on goods that consumers particularly value. An especially smart example of this is Ro Khanna’s proposal to repeal tariffs on coffee.

This is the way.

-GW

Great rundown. Another thing that would be useful all around is if business, large and especially small, would basically post honestly about this.

If they take a product off the US market due to tariffs, that product page on their site should say exactly that.

If a business closes or stops operating in the US because of tariffs, their website should say that, explicitly.

This may seem like asking these businesses to be political. But it’s not. It’s being honest.