The Policy Mistake from 1997 That’s Driving Up Healthcare Costs

And How to Fix It.

If you’ve waited weeks for a doctor’s appointment or paid an arm and a leg for healthcare services or for your insurance premiums, you’re experiencing the consequences of a poor policy decision made nearly three decades ago. In 1997, Congress capped the number of residency positions that Medicare would fund. That single decision created an artificial bottleneck in America’s physician pipeline that is now squeezing patients, driving up healthcare costs, and leaving qualified medical school graduates unable to practice medicine.

The United States faces a shortage of 124,000 doctors by 2033. This isn’t a problem of insufficient interest in medicine or lack of qualified candidates. Every year, thousands of medical school graduates go unmatched with residency programs. These are people with the intelligence and determination to complete one of the most rigorous educational programs there is. They could be excellent doctors. Instead, they’re being squeezed out, which is bad for them and bad for Americans’ healthcare costs.

The 1997 Cap’s Three Problems

Facing pressure to control Medicare spending, Congress decided to cap the number of residencies that Medicare would fund through its Graduate Medical Education payments under the Balanced Budget Act of 1997. This was a straightforward way to cut spending. The problem is that residency funding is essential to creating new physicians. Medical school graduates must complete a residency program to become licensed doctors. By capping the number of funded residency positions, Congress effectively capped the number of new doctors America could produce each year.

That cap has remained largely unchanged for nearly 30 years even while the American population has grown, aged, and spread. Medical spending has increased dramatically as the population ages and requires more care. In 1997, we spent about 13.2% of GDP on health; by 2023, we spent 17.6%. This makes an artificially induced doctor shortage extra unhelpful.

The 1997 residency cap created three interconnected problems that compound on top of each other. The most obvious is the mismatch between supply and demand. Even as America’s need for physicians has grown, the cap has prevented the system from responding. Thousands of medical school graduates now go unmatched every year. These individuals passed rigorous academic requirements, demonstrated the commitment and capability to become doctors, but then the system tells them there’s no room. It’s unfair, even cruel to them, and drives up costs while reducing access for patients.

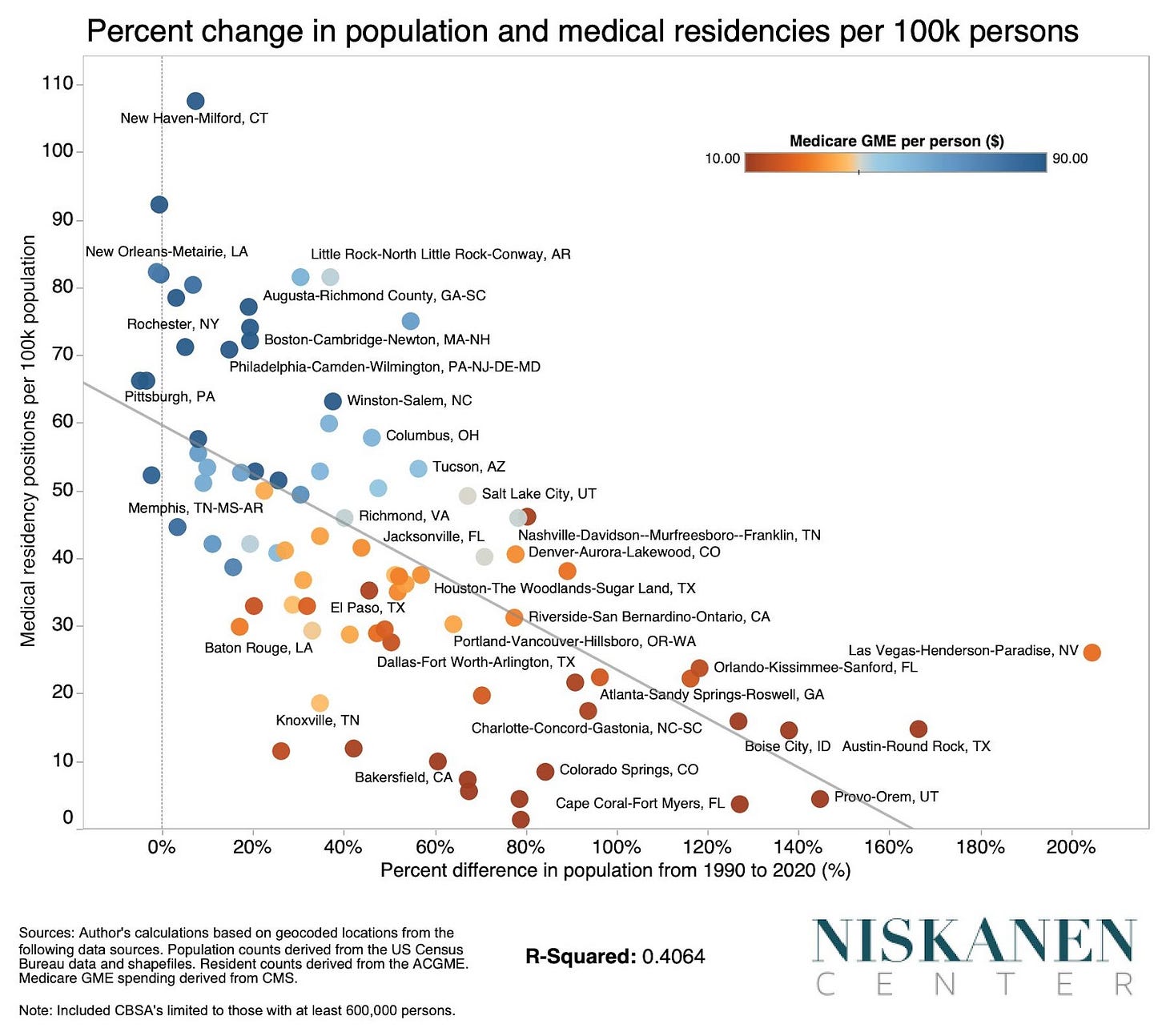

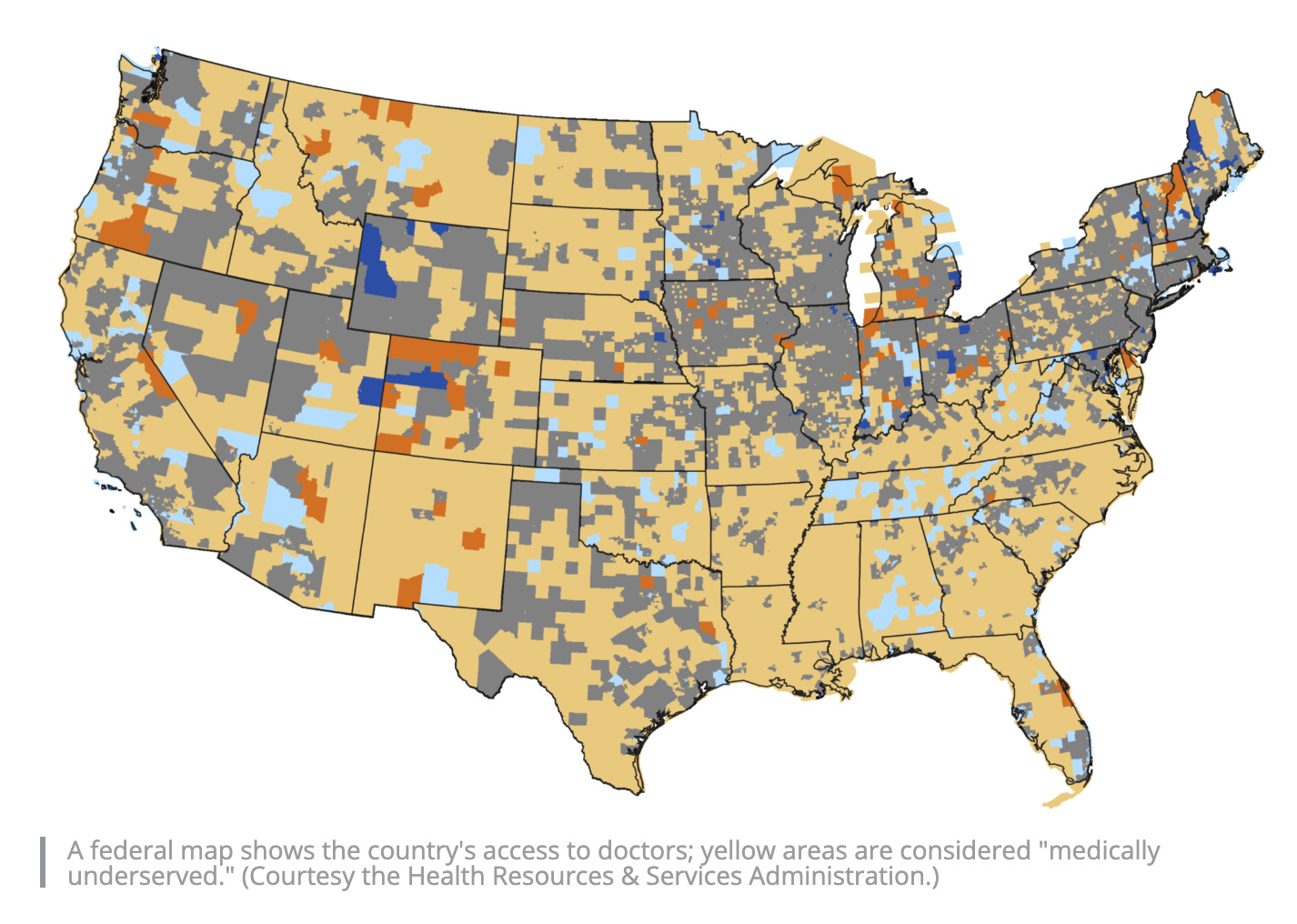

The second failure is geographic. The 1997 cap also froze the geographic distribution of residency funding. This is an issue because it means this funding has not shifted as the American population has and, because doctors tend to practice near where they did their residency, it means that the doctor bottleneck is especially acute in the places like Texas, Florida, Arizona, and North Carolina that are growing the fastest.

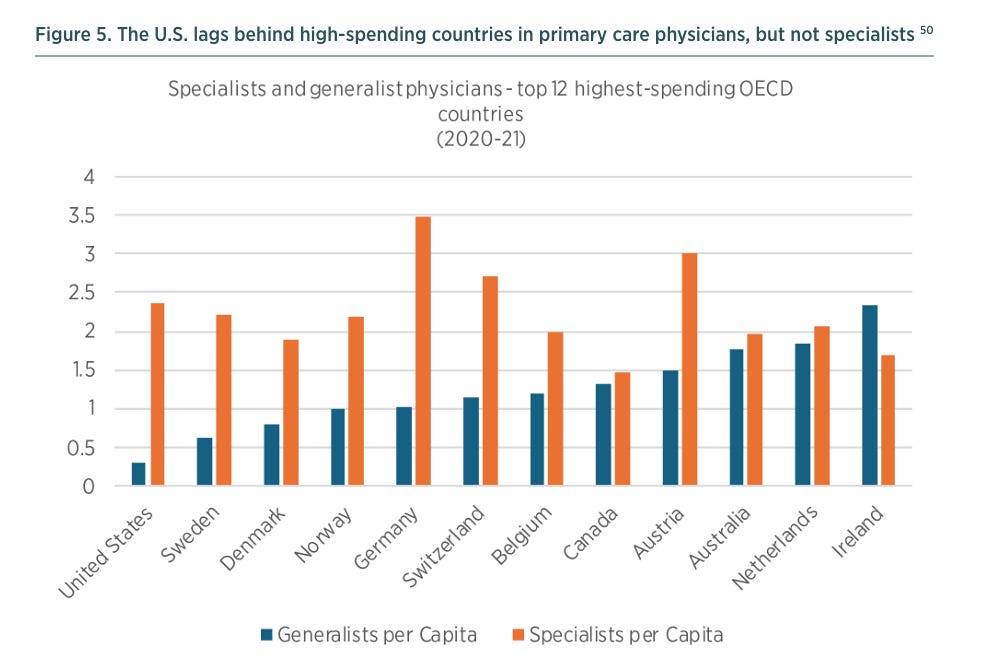

Third, the way Medicare funds residencies through the Indirect Medical Education program systematically disadvantages smaller facilities, rural areas, and primary care. The IME formula favors large academic medical centers and specialist training. This makes sense from the perspective of those institutions, but it creates serious problems for healthcare access. It is no coincidence that the doctor shortage is most severe in exactly the areas the funding formula disadvantages: smaller facilities, rural communities, and primary care.

The Real-World Cost

These three failures add up to real consequences for real people. This doctor shortage translates directly into higher healthcare costs, longer wait times, reduced access to care, and unsustainable workloads for the physicians who remain in the system. And, it’s worth noting that the Trump administration’s new $100,000 H1B visa fee is going to directly harm rural hospital’s ability to recruit doctors from abroad so this doctor shortage is only going to get worse unless we enact supply-oriented policy reforms like one I discuss further down.

When there aren’t enough doctors, prices rise. This is supply and demand at work. Patients who need care face limited options and therefore limited leverage to negotiate prices or shop around. Physicians can charge more because patients have fewer alternatives. Insurance companies face higher costs because there’s insufficient competition among providers. Those higher costs get passed on to patients through higher premiums, higher deductibles, and higher out-of-pocket expenses.

The doctor shortage also manifests as time. Wait times for appointments have grown longer across the country, but especially in underserved areas. Weeks or months can pass between scheduling an appointment and actually seeing a doctor. For patients, delayed care often means worse health outcomes, which means more expensive interventions down the road. It means lost wages from time off work. And it means stress and uncertainty. Long wait times and reduced healthcare access options can force patients toward emergency rooms for non-emergency care, which is more expensive for everyone and clogs up emergency departments that should be reserved for more acute emergencies.

The doctor shortage also creates a vicious cycle for the physicians who do practice in underserved areas. Fewer doctors means higher patient loads. Higher patient loads mean longer hours, more stress, and increased burnout. Burned-out physicians are more likely to leave the profession or relocate to areas with better work-life balance, which makes the shortage even worse. This cycle is particularly severe in primary care and rural medicine -exactly the areas the residency funding formula already disadvantages. All of these factors contribute to America’s high cost-of-living and to healthcare expenses being both one of the largest and one of fastest-growing components of household budgets.

The Way Out

Here’s the good news: there’s a solution on the table, and it has bipartisan support. The Resident Physician Shortage Reduction Act of 2025, sponsored by Representative Terri Sewell (D-Alabama), would increase the number of Medicare-funded residency positions by 14,000 over seven years. Over time, this would significantly expand the physician pipeline and begin to address the shortage.

The bill has attracted serious support. Sewell’s bill on this in the last Congress had 169 Democratic co-sponsors and 23 Republican co-sponsors. The American Hospital Association backs this idea. This is not a partisan issue; It’s a practical problem with a practical solution that members of both parties support.

What makes this particularly promising is that reform might be achievable without significant new federal spending. The current residency funding approach is so inefficient and poorly structured that it might be possible to reform the system in a revenue-neutral way. By fixing the structural problems with the IME formula and reallocating existing resources more efficiently, Congress could expand residency positions while addressing the geographic and specialty distribution problems at the same time.

This is the kind of policy reform that should be easy to pass. It addresses a real problem. It has bipartisan support. It could potentially be done without increasing the deficit. And it would directly benefit millions of Americans by expanding healthcare access and putting downward pressure on healthcare costs. As soon as the government reopens, we should pass the Resident Physician Shortage Reduction Act of 2025.

-GW

This is a great article, except for the part that says “physicians can charge more”. We can’t. Our pay is tied to MPFS, which decreases every year, or is artificially determined by hospital administrator’s decisions of “fair market value”.

Maybe you meant to say hospitals/ health systems can charge more for care.

The need for primary care docs is so acute! My daughter is a 3rd year Family Medicine resident and their workloads are so high that most grads from her program choose to work an 80 percent schedule because full-time is unsustainable. In addition to the sheer lack of bodies to do the work, dealing with patient questions & requests via patient portals and the ever worsening prior authorization process has greatly increased work that happens outside the exam room.