Portable Benefits Help the Strivers

9-to-5 is not the only work worth doing.

In 2010 and 2011, during the bottom of the Great Recession I was a recent college grad having trouble finding a full-time job. I was not the only one. In December 2010, the unemployment rate for recent college grads was 7.9% but the underemployment rate for recent grads was 45.8%(!). So I did what a lot of people do — I started doing an independent job. In fact, I got three. I was living in Boston, so I led Freedom Trail tours by day and, in the evenings, I’d split my time between SAT tutoring and doing freelance political analysis for a company in London. As a special treat for you dear reader, here’s a picture of me in the Freedom Trail get up. :-)

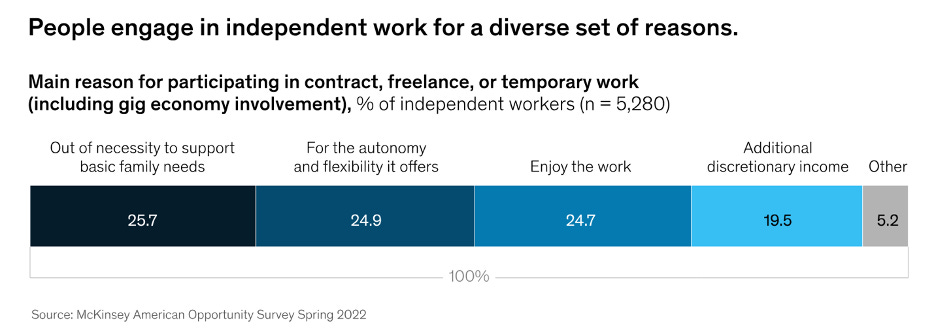

Whether it goes by the name independent work, gig work, or side hustles, a lot of people in America like taking these kinds of jobs for all kinds of reasons including the combination of pay and flexibility. These people are strivers trying to make some money and provide for themselves and their families. We should want them to be able to flourish in this kind of work.

Here’s the problem though: the way benefits work in the American economy don’t work for gig workers and independent contractors, and that raises their cost-of-living. You can also see this in the survey data. When asked, independent contractors and gig workers say that they like being able to set their own schedule, they like the extra money, and they like the idea of being their own boss. The biggest area of frustration though is benefits like paid time off and health insurance.

The good news is that there’s an innovative idea called Portable Benefits that can help with that.

How We Got Here

America's benefits system was built for a different era. The post-World War II era was when we built the modern system that locked in the idea that health insurance, retirement contributions, and other benefits should be tied to your employer. That system made sense then; companies wanted to attract and retain workers, and employees valued the security of a comprehensive benefits package.

But that model assumes something that's increasingly untrue: that you work for just one employer at a time. When you don’t, you end up in a situation where even though you are gainfully employed, you don’t work for any one company enough for benefits to make financial sense for the economy. When I was doing my three side hustles during the recession, the Freedom Trail company wasn't going to offer me health insurance for leading 5-6 tours a week. The tutoring company wasn't going to set up a 401k for me. And benefits from doing freelance political analysis for a company in London? Not a chance. None of these gigs alone was substantial enough to justify the administrative burden or financial costs of traditional employee benefits, especially given that for each of them, I had the opportunity to accept or turn down work as it came up.

This crack in the system creates a catch-22 for the more than 27 million Americans that work independently full-time. They’re Uber drivers, freelance graphic designers, part-time consultants, weekend photographers, and people like my past self juggling multiple income streams. Yet our benefits system still operates as if everyone works 9-to-5.

Being Pro-Worker Means Letting Workers Have Flexibility They Want

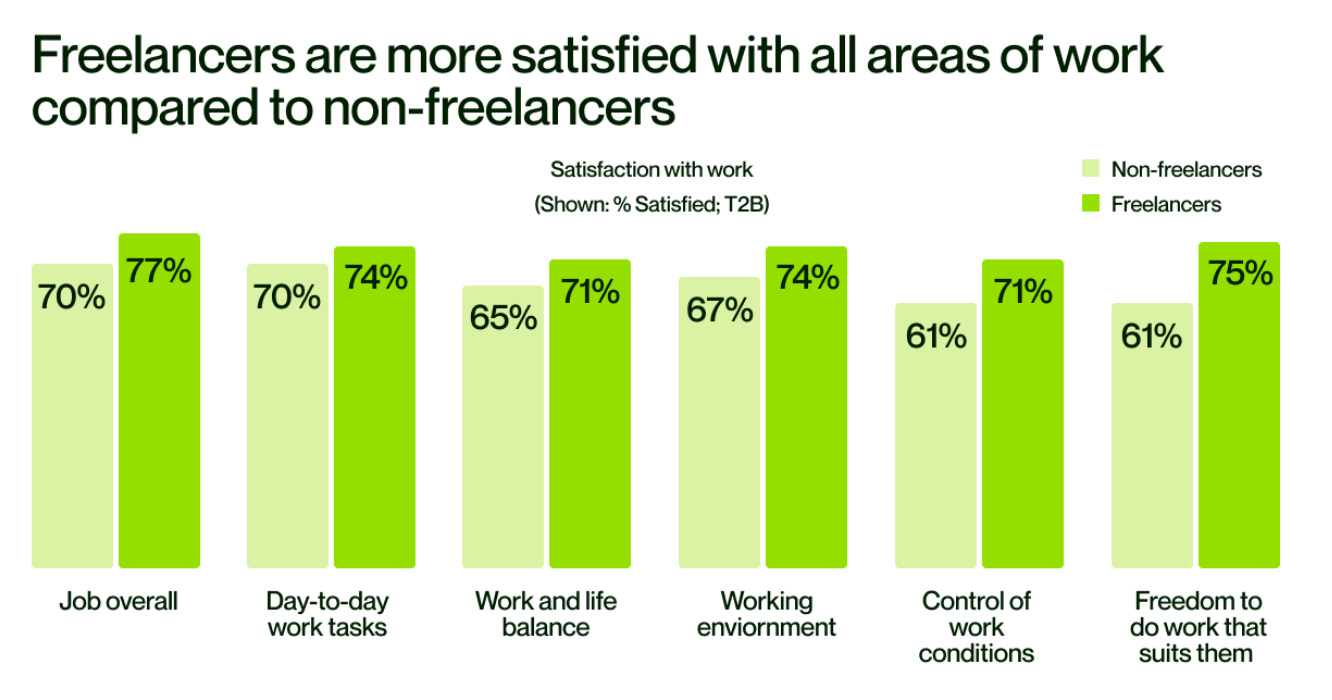

There’s a recurring myth that independent workers are being taken advantage of. That’s not what surveys suggest. Across a wide variety of metrics, freelance workers are more satisfied with their jobs than non-freelance workers.

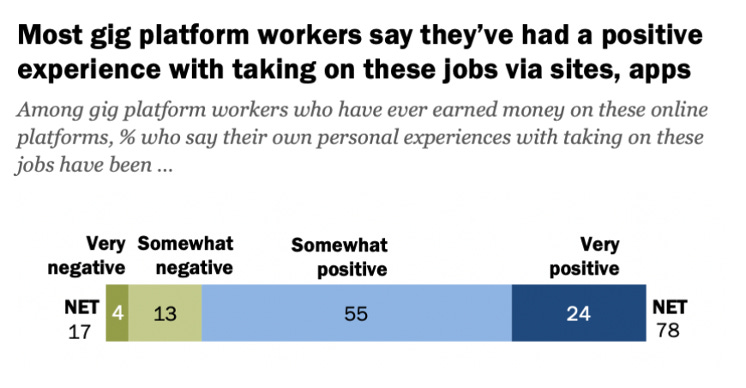

84% of full-time independent workers say they’re happier working on their own, 75% say they plan to continue working independently (versus just 14% who say they’d like a permanent traditional job). When asked about their experience, 79% of workers who have done gig-platform work report feeling positive about their job, while only 17% felt negatively about the work. And, independent workers report feeling more optimistic about their economic futures than traditionally employed workers at the same income level. None of this screams ‘exploitation.’

And yet, unfortunately, that myth, and then the accompanying presumption that the only good jobs are 9-to-5 jobs, undergird some very misguided approaches to independent workers Exhibit A on this is California’s AB 5. That bill, passed in 2019, tried to force companies to classify independent workers as employees even though gig workers consider themselves independent contractors by a more than two-to-one margin.

AB 5 was a disaster from the outset. Freelancer writers and content creators couldn’t get work. There were hundreds of stories that poured in of workers getting hurt by AB 5.

“Please understand that my mother, a translator and interpreter for over 30 years, will no longer be allowed to speak for immigrants in the court system because of AB 5.” -Mayan.

“My husband is a band leader. Can’t get paid to play music on the weekends anymore because according to AB5 he’d have to make the singer, drummer, and bass player employees of the band.” -Melissa.

“I’m an older woman with two teaching credentials living in a small county who cannot find employment outside of independent contractor online teaching jobs. One company has already announced they will no longer contract with California teachers. I care for a disabled husband. I will lose my home if I cannot work for these companies.” -Jan.

And there are a lot more stories like this. AB 5 destroyed more than 4% of all jobs in the affected occupations. Few independent workers were converted to full-time traditional employees (the ostensible goal of the bill). The bill’s implementation caused such widespread problems that it had to be amended the next year, but all these amendments did was create exemptions for certain very specific industries and occupations like photographers and translators but left the rules in place for others, and kept the underlying problematic framework. The problem with AB 5-style approaches which have influenced the fortunately not-passed PRO Act as well as some state-level bills is that they ignore what workers actually want: the ability to work flexibly while still having access to the security that benefits provide.

Independent work is a key source of income for those on the margin of the labor market such as people with loved ones they need to care for, people with criminal records, and people who live in underprivileged areas. Not to put too fine a point on it, but these are the exact kinds of people that we Democrats say we want to help. We should be on their side when they say they want work flexibility.

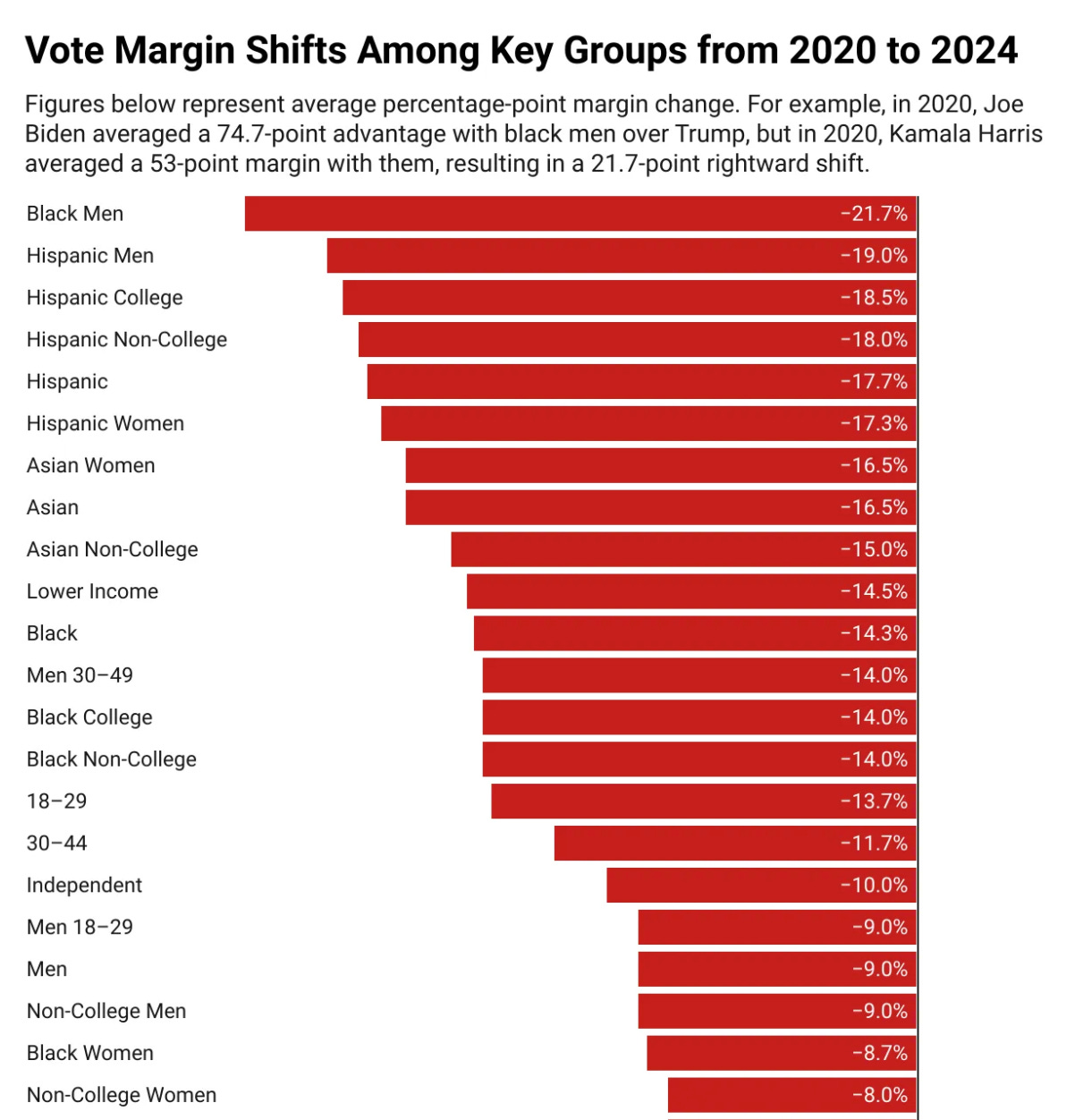

Moreover, curtailing independent workers’ economic freedoms in this way is especially bad for some of the voting blocs that turned against Democrats in last year’s election. Independent workers aredisproportionately male, young, non-white, non-college educated, lower income, and from immigrant backgrounds. Taking away their economic opportunities based on some very misguided notions about the labor market is not the way to win them back.

So then if AB 5-style red tape isn’t the way to help, what is? Portable benefits.

What Portable Benefits Are

Think of portable benefits as benefits that belong to you, not your employer. Instead of health insurance and retirement contributions being tied to one specific job, portable benefits follow you wherever you work whether that's driving for Uber on weekends or freelancing as a graphic designer or anything in between.

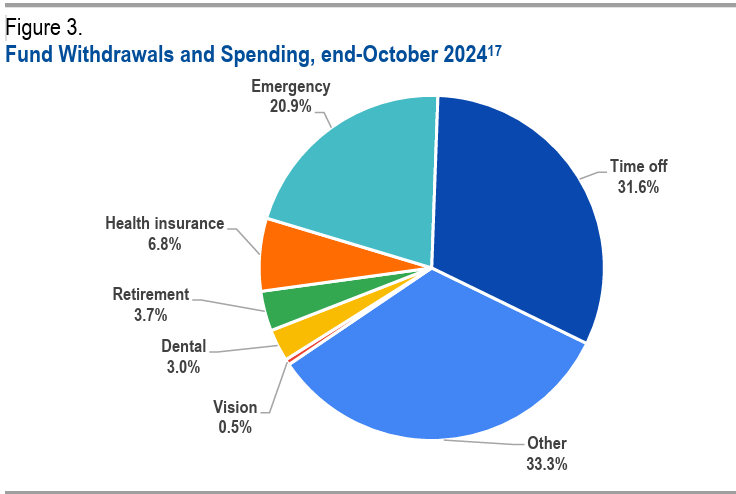

Wisconsin’s new Portable Benefits program (recently passed by both chambers of the legislature but still awaiting the Governor’s signature) demonstrates well how this can work in practice. Companies contribute a percentage of your earnings (typically around 4% based on current pilot programs) into an individual account that belongs to the worker. You can use these funds for health insurance premiums, retirement savings, or even to replace lost income when you're sick or taking time off. The key difference is that these benefits stay with you whether you're working for one platform or juggling multiple side hustles.

Utah took an even broader approach, allowing any company using independent contractors to offer portable benefits, not just app-based platforms. Pennsylvania is testing the waters with DoorDash's six-month pilot program, giving real-world data on how these systems work in practice.

Under all of these plans, crucially, workers remain independent contractors with all the flexibility that provides; they can still set their own hours, accept or decline work as it comes in, and work for multiple companies or platforms simultaneously. Interestingly, this pilot showed that portable benefits were especially liked by workers who get more than a quarter of their income from independent work.

Alabama took the boldest approach yet, becoming the first state in the country to offer a tax-advantaged way for businesses to contribute to benefits for independent contractors. Under Senate Bill 86, signed in April, both businesses and contractors get major tax breaks: employers can deduct the cost, and workers don't pay taxes on the value received. That’s great because when both the worker and the platform save on taxes, there's more money available for actual benefits. That's not just good policy; it's a direct cost-of-living reduction for all independent workers in the state. The law also explicitly protects worker classification, stating that participation in this program does not alter a worker's classification, so it’s basically an iron-shield against AB 5-style damages.

The beauty of portable benefits is that they solve the core problem: how do you provide security without sacrificing flexibility? Instead of forcing square pegs into round holes by making everyone a traditional employee, portable benefits create a new category that fits how millions of Americans actually want to work.

For the Strivers!

We Democrats like to think of ourselves as being pro-worker. That should start with respecting what workers want. Many workers are strivers who strongly prefer the flexibility and opportunity that independent work provides. Portable benefits do exactly that. They give millions of Americans the security they need while preserving the flexibility they want. That's not just good policy for the freelance strivers; it's good politics for anyone who believes workers should have the freedom to choose how they earn a living.

-GW