Ozempic For All

More Good Health, For Everyone

The intellectual core of The Rebuild is bringing down the cost of living, but the emotional core is better described as trying to create “more good things, for everyone.” Yes, it’s about supply and abundance and growth and technology and all the wonky things we talk about but it’s also about helping Americans lead prosperous, fulfilling lives, and not just elite Americans but regular everyday goes-shopping-at-Walmart Americans.

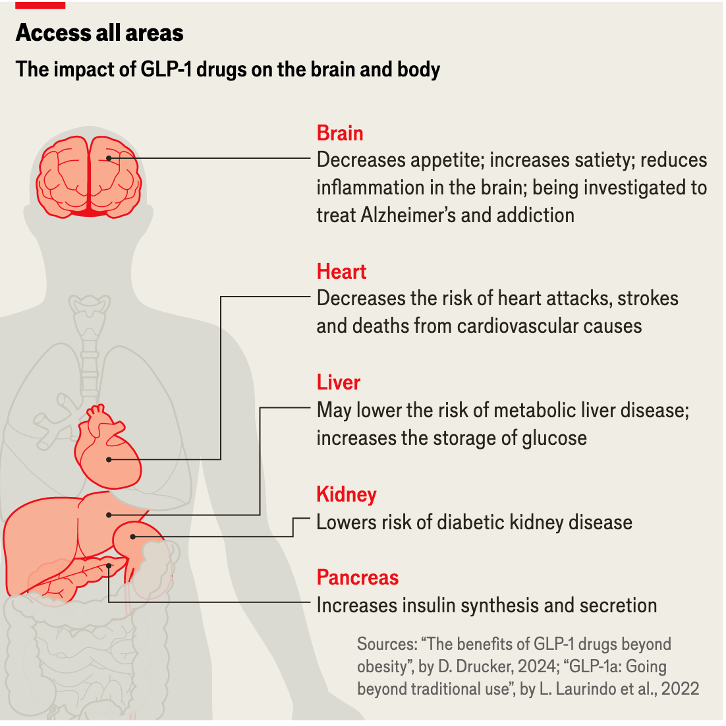

Meanwhile, there are some incredible technological and scientific breakthroughs happening around from next generation geothermal to self-driving cars, but the most amazing of them is the rise of GLP-1s like Ozempic, Wegovy, and Mounjaro. By now, you’ve probably heard about their weight-loss benefits, but scientists are discovering that they have all kinds of other benefits too: they prevent strokes and heart attacks, fight kidney disease and Parkinson’s, curb addiction, and lower risks for several particularly nasty cancers. They have so many benefits that the Wall Street Journal asked half-jokingly but also half-seriously: “Should Ozempic be added to the water supply?”

Given the huge array of benefits of these new wonder drugs, it’s important to ask how we make sure that every American for whom these drugs are appropriate has access to them. In other words, how can we get Ozempic for All?

The Access Problem

Here's the brutal cost reality: these life-changing medications cost about $500 per month without insurance coverage. That's $6,000 a year, so for a lot of people, that's not happening. This becomes problematic as obesity is negatively correlated with social class —lower income and less educated adults are more likely to be overweight.

With insurance, the situation can vary a lot. While some employer plans and Medicare cover GLP-1s for diabetes, coverage for weight loss is spotty at best. Patients often face copays of $200 or more per month, or they get stuck in prior authorization hell where insurance companies require them to go through multiple other treatments first.

This creates a perverse two-tiered system. Wealthy Americans and those with premium insurance plans can get access to medications that can prevent heart attacks, strokes, and diabetes complications. Meanwhile, many of the Americans who would benefit most (those dealing with obesity-related health issues and who can't afford premium healthcare) are priced out entirely. The moral case is straightforward: healthcare shouldn't be rationed by wealth. When we have medications that can prevent heart disease, stroke, and diabetes — conditions that disproportionately affect lower-income Americans — restricting access based on ability to pay is deeply unfair.

This is a problem that affects all of America. Though there are some geographic differences in obesity rates, the health problems that GLP-1s help alleviate are everywhere problems. Even the most in-shape state (Colorado) has an obesity rate of 25%. People in every state get diabetes. People in every town can have a heart attack.

The Case for Government Subsidization

Two-tiered access to GLP-1s isn't just unfair, it's economically upside-down. Americans most likely to develop expensive complications from untreated obesity are the ones least able to afford the medications that could prevent those complications and so we're essentially guaranteeing higher healthcare costs down the road by de facto rationing access to preventive treatment today.

The idea of government-subsidized GLP-1s isn't some radical left-wing fantasy; it's economic common sense. We already do this all the time with medications and treatments that save money in the long run. Take insulin for example. Medicare and Medicaid cover it because, on top of being necessary, untreated diabetes costs the system far more than the medication itself. Vaccines are another example. We heavily subsidize them because preventing diseases is a lot cheaper than treating them. The same logic applies here.

Obesity-related healthcare costs the U.S. about $173 billion annually, and that doesn’t include all those other medical problems that GLP-1s may be able to address like addiction. It also does include costs outside of direct medical expenses like lost productivity, disability payments, and early mortality. When you're already spending enormous sums treating heart attacks, strokes, and dialysis, spending a bit extra upfront to prevent these diseases isn’t just the humane thing to do, it’s smart long-term fiscal management.

When someone has a heart attack, the initial hospitalization (not including any follow-on care) costs, on average, between $18,000 and $30,000. Conversely, Denmark has been able to negotiate a price of $130 per month for Ozempic, so preventing even one heart attack pays for a whole lot of coverage.

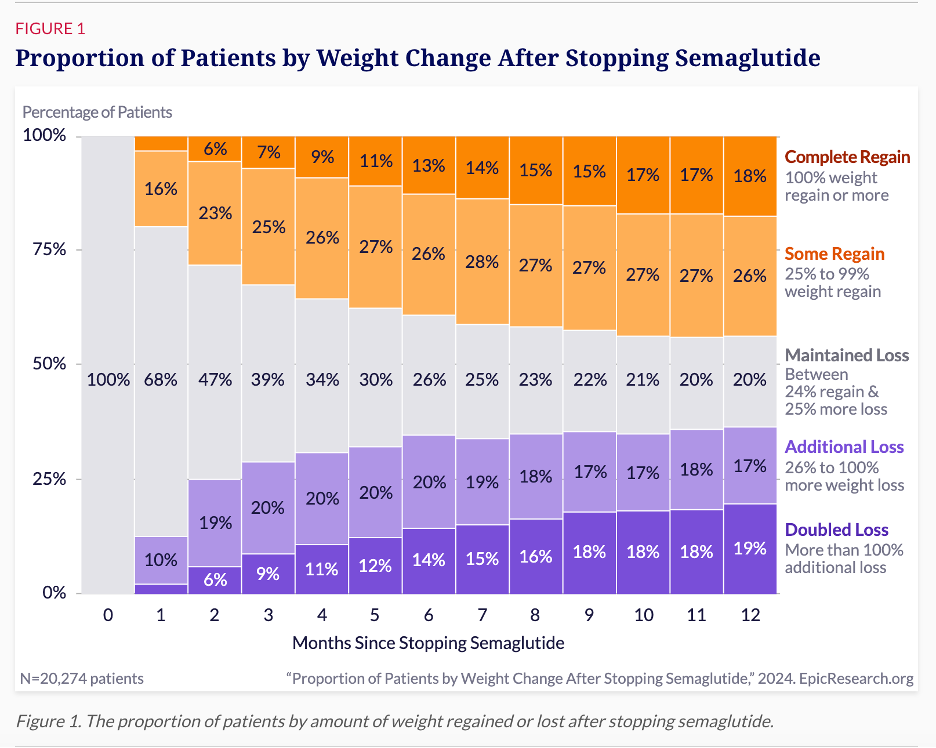

Just on the weight loss side, it’s also important to note that while some patients may need to stay on GLP-1s long-term, many may not need to, most people who come off of GLP-1s do not gain all the weight back and more than a third continue to lose significant weight even after discontinuing them.

The federal government is going to spend money on obesity-related health complications either way. The question is whether we want to spend it efficiently on prevention or inefficiently on emergency treatment after the damage is done. This isn't pie-in-the-sky socialism; it's investing logic applied to health spending.

Implementation- So How Do We Actually Do This?

There are four complementary strategies based on already existing programs and government authorities that could help us get there. Think of my approach more like bringing together a toolkit rather than creating a new government apparatus.

A) Government Bulk Purchase Agreements: The Foundation of More

The smartest place to start is with bulk purchasing agreements, essentially scaling up what we did so successfully with COVID vaccines. The federal government would negotiate directly with manufacturers to purchase millions of doses annually in exchange for significantly reduced per-unit pricing. This isn't price control; its volume discount negotiation, the same thing Costco does, just bigger.

When you're guaranteeing a pharmaceutical company that you'll buy millions of doses per year, you get leverage that no individual insurance plan can match. The manufacturers love this because it gives them predictable revenue streams they can use to justify continued investment in production capacity. We health care consumers love it; bulk purchasing typically delivers significant cost savings compared to list prices; the COVID vaccines once again give a recent example of this.

If Denmark can get Novo Nordisk to agree to a $130 a month price, I don’t think it’s unreasonable to think that the U.S. government could get an initial price of $100 a month given that it would be buying millions of doses a month.

The costs can sound large but in fact they’re relatively small compared to how much we already spend, and so if they obviate the need for much of that spending, this program could mostly or maybe even fully pay for itself. At $100 a month multiplied out by 12 months a year and let’s say 10% of all adults (so that 25.8 million people), you’re looking at about $32.2 billion per year. Sounds like a lot. But remember Medicare and Medicare combined spend about $1,900 billion a year. Spending on these bulk purchases that lower those Medicare/Medicaid costs is a money saver and a key initial step to making Ozempic For All a reality.

These bulk purchase agreements would supply multiple programs simultaneously. Instead of Medicare negotiating separately from Medicaid, and everyone competing against each other, we create one massive purchasing pool that maximizes taxpayers’ bargaining power. The manufacturers get the scale they want, taxpayers get better deals, and we avoid the administrative headache of managing multiple separate negotiations.

B) Medicare Coverage: Immediate Impact for Seniors

With bulk purchasing providing the supply at negotiated prices, expanding Medicare coverage becomes much more affordable. Medicare already covers GLP-1s for diabetes treatment, so this isn't about creating new administrative infrastructure. This makes particular sense because older Americans are exactly the population most likely to benefit from GLP-1s' cardiovascular and kidney protection effects. We're not just treating obesity here; we're preventing heart attacks, strokes, and diabetic complications in the population most vulnerable to these conditions.

Medicare expansion also creates immediate political momentum. Seniors vote, and they'll notice when they can suddenly afford medications that were previously out of reach. That builds constituency support for the broader program.

C) Medicaid Buy-In: Covering Working America

Here's where the program gets really interesting. A Medicaid buy-in option would allow working-class Americans, i.e. people who earn too much for traditional Medicaid but can't afford premium private insurance, to purchase GLP-1 coverage through the Medicaid system. Since Medicaid would be part of the bulk purchase system, buy-in participants would get access to the same bulk-purchased GLP-1s at affordable copays.

This is a good way to help solve the political problem of income-based subsidies. There’s a lot of understandable frustration from people who feel like they make too much to get help from the government but too little to be financially comfortable. This policy is meant to help them too. Instead of creating arbitrary cutoffs that lead to people asking why the person who makes slightly less than them got a benefit that they didn’t, you're offering everyone the option to buy into a program that delivers strong value.

D) Generic and Biosimilar Fast-Tracking: Key to Long-Term Affordability

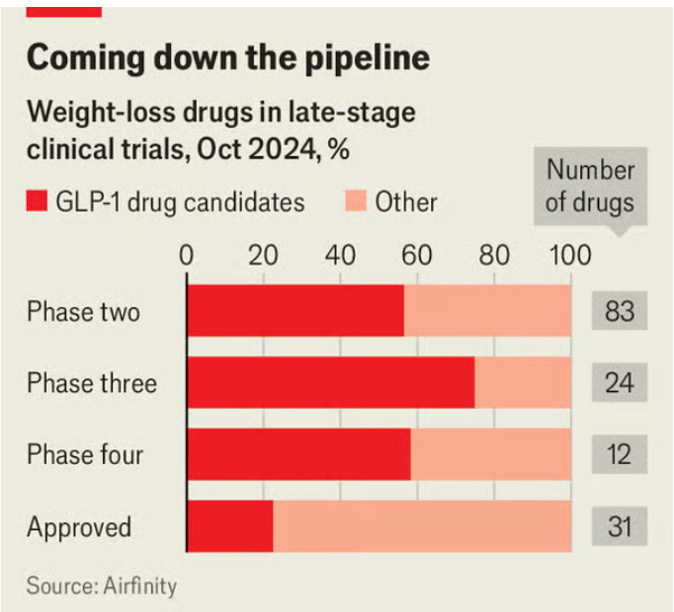

The final piece focuses on the future. While bulk purchasing and coverage expansion help people today, fast-tracking generic and biosimilar approvals ensures long-term affordability. The price tag for the government covering these drugs is going to be expensive in the short-term. To make the program long-term viable, you have to bring the costs of GLP-1s down. Fortunately, we have many GLP-1s that are coming down the pipeline.

So the question then becomes how do we get those drugs through the pipeline faster so that we can get more competition and lower prices sooner. A good way to do that is to do fast-track regulatory approvals of generics and biosimilars. That will likely be in the late 2020s and early 2030s. The FDA already has fast-track authority for drugs addressing unmet medical needs. Applying this to obesity medications makes sense given the scale of the public health challenge.

How It All Fits Together

These four prongs work together. Bulk purchasing makes expanded coverage affordable. Medicare coverage creates immediate political momentum and serves the highest-need population. Medicaid buy-in extends access to working Americans who need it most. Generic fast-tracking ensures the program becomes even more cost-effective over time.

Pharmaceutical companies get what they want: predictable, large-scale demand and continued patent protection. The government gets what it wants: better prices and long-term cost control. Most importantly, the American people get what we need: access to life-changing, and in many cases life-saving, medications regardless of our employment situation or income level.

Finally, and I cannot emphasize this enough: This isn't a revolution. This isn’t radical. This isn’t anti-capitalist. It's a practical, incremental policy improvement that builds on systems that already work.

More Good Health, For Everyone

I want you to imagine a world with more seniors at their grandkids’ birthday parties, more years of good life with a beloved spouse, fewer tears in hospitals as people get told which stage their cancer is in, more evening walks, less drug and alcohol addiction scourging lives, and so much else besides. That’s the world we can get to faster if we get the policy right on this. That’s what we get if we win. That’s what the combination of capitalism, the welfare state, and technology does; it creates more good things, for everyone. And that includes More Good Health, For Everyone.

-GW

Unfortunately, as far as I am aware, generic fast tracking does not exist. (That doesn't mean that the FDA can't update its procedures.). "Unmet medical need" has a specific definition and that generally does not include questions of access.

Fast-tracking generics would infringe on the current intellectual property rules of 7 years of exclusivity, which is a key part of the economic math that drives the biotech industry. Changes to the IP regime could undermine a great deal of future therapies.

Pricing negotiation and bulk purchases are the way to go until Ozempic comes off patent, which is not that far away in the long run, and with so much non-generic competition coming down the line as well, plus all of the compounding pharmacy work that is still going on.

Accelerating access by 3-4 years does not seem worth such a major disruption the medical innovation pipeline as changing the IP rules.

Ha you think we live in a functional country lmao

I understand why workplace based health insurance doesn’t pay for stuff that only benefits in the long term because people change plans all the time, but I don’t understand it for state insurance like Medicare, Medicaid, or state employee health insurance because in general you’ll have the same plan for years and years