It’s Not “Greedy Developers” – It’s Local Control

How Zoning Reforms Failed in Colorado and Minnesota

In early May 2025, two ambitious housing reform efforts – one in Colorado and one in Minnesota – collapsed in strikingly similar fashion. In Colorado, a modest “Yes in God’s Backyard” (YIGBY) bill to let churches, schools, and colleges build affordable homes on their land died in the state Senate without a vote. In Minnesota, a bipartisan package of zoning reforms was blocked in a Senate committee despite sailing through earlier hearings with broad support. These twin failures highlight a common roadblock: local control. In both cases, the primary opposition came not from developers or corporate landlords, but from city governments and their associations fiercely guarding local zoning power. This runs counter to a popular narrative that blames greedy developers for obstructing housing progress. Instead, the evidence suggests that “home rule” ideology and the reliance of "vetocracies” stand as obstacles in the path of reform.

Colorado’s YIGBY Bill: Home Rule Strikes Again

Colorado’s House Bill 1169 was a centerpiece of Governor Jared Polis’s 2025 housing agenda. The bill would have overridden local zoning laws to allow residential development on land owned by faith organizations and schools, effectively letting churches, synagogues, and other institutions build affordable housing by right on their property. Supporters saw it as a creative way to cut red tape and use underutilized land for public good, especially amid a statewide shortage of 100,000+ housing units. The measure sailed through Colorado’s House in March and even passed a Senate committee, buoyed by backing from nonprofits, congregations, and school districts eager to provide homes for teachers and low-income families.

However, when the bill reached the full Senate, it hit a wall of local-control resistance. Colorado’s municipalities and county officials viewed HB 1169 as a direct affront to “home rule” – the state constitutional doctrine that grants cities wide autonomy over local matters like zoning. The Colorado Municipal League (CML), representing town and city governments, vehemently opposed the bill, warning that it “more than any other recent legislation, infringes on constitutional rule authority to regulate zoning, a matter of local concern." In a position paper, CML argued that forcing cities to allow housing on church lands would “circumvent existing planning and zoning processes,” create a “privileged class of property owners” (religious institutions), and undermine community plans. Local officials bristled at this state “preemption,” insisting that land use is a “matter of local concern” and should remain in city councils’ hands.

Facing a unified front of city and county opposition – and hearing fears that YIGBY could lead to “luxury developments that do not help solve our housing crisis” if profit-motivated actors exploited the law, Senate leaders quietly pulled the plug. Lacking enough votes in the Democrat-controlled chamber, sponsors asked to delay the bill’s vote until after the legislative session’s end, a maneuver that effectively killed the measure. What was meant to be a good-faith, incremental step to spur affordable housing on church lands instead became the latest casualty of Colorado’s state-versus-local zoning feud.

That feud has been simmering for years. In 2023, Governor Polis’s much broader land-use bill (which sought to mandate denser zoning around transit and end single-family exclusivity in many areas) was similarly gutted after fierce backlash from municipalities. Lawmakers removed nearly all upzoning requirements from the 2023 bill, and it ultimately died, underscoring the clout local governments wield at the Capitol. By 2025, Polis and his allies tried a narrower approach with the YIGBY bill, hoping a focus on church-owned land (and a requirement that any housing include an affordable component would win more acceptance). It didn’t.

Minnesota’s Zoning Reforms: Bipartisan Support Meets Municipal Veto

Across the country in Minnesota, an even broader zoning reform effort met a similar fate in 2025. Heading into the legislative session, a “Yes to Homes” coalition of strange bedfellows – affordable housing advocates, environmental groups, builders, realtors, the state Chamber of Commerce, social justice and faith organizations – lined up behind a package of bills to open up housing construction statewide. The proposals, crafted with bipartisan cosponsors, aimed to curb the most restrictive local zoning practices. Among other changes, the bills would: Reform zoning laws to allow duplexes, triplexes, and small apartments in single-family neighborhoods and commercial areas, while eliminating costly regulations like excessive lot sizes, parking minimums, and square footage requirements that drive up housing prices. Streamline the approval process by creating fast-track permitting for compliant projects and prohibiting micromanagement policies that force HOAs or dictate architectural details.

It was an ambitious but carefully negotiated agenda. Notably, reformers had already compromised by dropping the most controversial ideas: the package did not attempt to completely end single-family zoning statewide, nor did it force cities to allow large apartment complexes in all single-family neighborhoods. Lawmakers had met with city lobbyists in the interim, trying to find middle ground. In effect, this was incrementalism at work – a “bare minimum” slate of changes, as the Senate Housing Committee chair put it, to at least chip away at exclusionary zoning.

Yet even this moderated approach ran into a brick wall of local government opposition. Representatives of city governments packed committee hearings to protest the bills. The League of Minnesota Cities and the Coalition of Greater Minnesota Cities (associations representing municipal governments) formally opposed the reforms, trotting out familiar arguments. They warned that the state was imposing a “one-size-fits-all” mandate on diverse communities, that cities would be saddled with infrastructure costs for new development, and that local elected officials needed to retain control to respond to their residents’ concerns. In essence, city leaders insisted they were already addressing housing in their own way, and state interference would do more harm than good. It’s the same home-rule refrain heard in Colorado: leave it to local government, we know best.

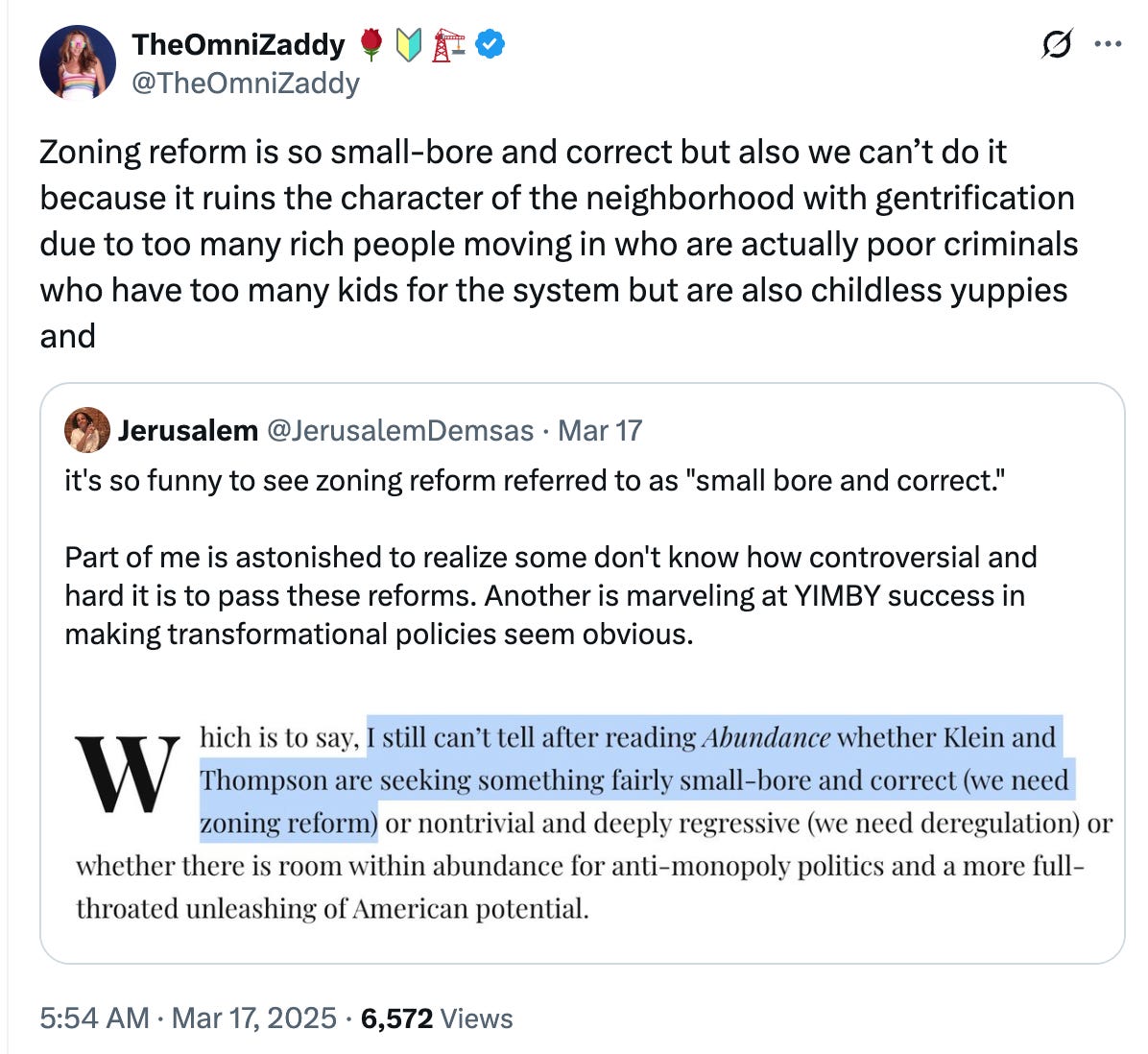

This highlights the disconnect when advancing zoning reform or the critics that have emerged discussing the recent Abundance book by Ezra Klein and Derek Thompson, who spend a good part of the book on breaking down how vetocracies have hampered our ability to build, critics like Zephyr Teachout have dismissed the fight surrounding zoning reform as “smallbore and correct,” which vastly undermines the difficulties and obstacles that arise when trying to pass these housing initiatives.

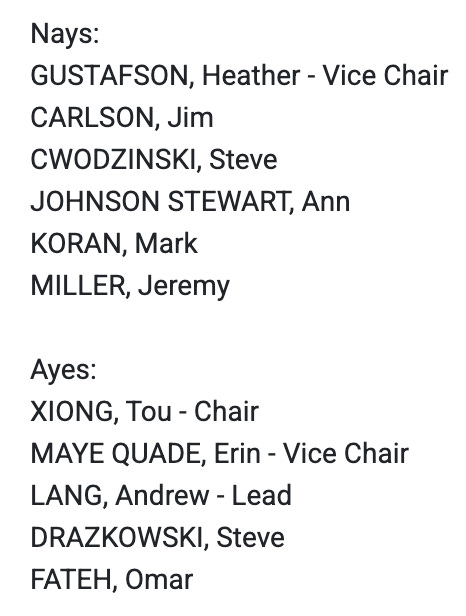

The broad coalition of supporters and a sympathetic House of Representatives (controlled by the DFL, Minnesota’s Democrats) got the bills through initial committees with overwhelming, bipartisan votes. But when the measures reached the Senate’s State and Local Government Committee, they hit a dead end. Swayed by city hall lobbying, a handful of senators from both parties peeled off:

In a pivotal committee meeting, four Democrats and two Republicans voted down even a pared-back amendment that bundled a few key reforms. The amendment would have merely limited cities to one parking space per unit, banned cities from mandating HOAs or vanity design rules, and required an administrative approval option for conforming projects – hardly a radical takeover. Yet it failed on a 6-5 vote. Sen. Heather Gustafson, while defending her “no” vote, echoed the local-control talking points: “This shifts power towards developers, not communities,” she argued, decrying a supposed “one-size-fits-all” approach and noting the bill didn’t guarantee affordable units. Her cities were already doing a good job on housing, she insisted, so they should retain control.

And with that, Minnesota’s 2025 zoning reforms were pronounced “all but dead for the year”. It was a bitter disappointment for housing advocates. Despite an unprecedented right-left alliance and public rallies at the Capitol, “meaningful zoning reform” was postponed to another day. Importantly, this was the second year in a row state housing bills succumbed to city opposition.

As the Senate author, Lindsey Port, lamented, “We really brought the bare minimum… This was our opportunity to do a small fraction” for housing – yet local control still prevailed. Port isn’t giving up. “I think these bills, in some version, are inevitable,” she said, throwing down a challenge to the city lobby: it’s “up to the cities and the city lobbying groups to decide how much fight they want to put into this – how much reputational damage… they want to [risk]” by blocking needed housing reforms. Her message underscores a brewing political fault line: on one side, frustrated housing advocates and legislators who see statewide action as urgent; on the other, municipal officials and home-rule purists determined to hold the line.

Local Control vs. “Greedy Developers”: Rhetoric and Reality

Local control advocates often deploy a pro-community, anti-developer rhetoric to justify their position. We saw this in Minnesota, where a senator claimed the modest zoning bill would empower faceless developers at the expense of “communities”. In Colorado, the Municipal League similarly darkened the picture of HB 1169 by suggesting that without strict guardrails, religious landowners (or their developer partners) might build luxury condos that “do not help our housing crisis”. The irony is that these reforms were designed to remove artificial constraints (minimum lot sizes, bans on multi-family, etc.) which currently inhibit developers from building more moderately priced housing. By blocking such reforms, local governments are in effect protecting the status quo – a status quo that benefits incumbent homeowners and NIMBY neighborhood groups who fear change to “community character.”

“It’s been a years-long battle between cities protective of local control of development and housing builders who have complained about onerous rules that increase costs.”

Developers are not all saints, of course, but in this policy arena they and housing advocates are largely on the same side – pushing for fewer restrictive rules so that more homes (market-rate and affordable alike) can be built. City governments and aligned homeowner groups are on the other side, fighting to maintain their gatekeeping power over what gets built, where, and when. It is local city councils that often say “no” to apartments, not shadowy corporate tycoons. And it is taxpayer-funded city lobbyists who annually descend on state capitols to say “no” on a broader scale – opposing any state law that would limit local zoning authority. As California councilmember Sergio Lopez put it, “The [league of cities] has pretty much always taken the position of opposing most major housing bills”, using cities’ collective clout to water down or kill reform proposals.

As Ezra Klein put it in a recent interview with Sam Seder, “I don't think you can say the reason you can't build nonprofit affordable housing is because we've overcommodified housing.”

The instinct to pin the blame solely on corporate villains or commodification, he argues, misses the structural reality: “When you create this level of proceduralism, this level of veto points, they get captured by interests over time.” For Klein, the abundance agenda isn’t about identifying a single bad actor—it’s about confronting a political operating system that enables obstruction from any well-organized interest, however well-intentioned or well-organized, to veto progress

This critique is especially relevant in states like Colorado and Minnesota, where housing reform bills failed not because of developer influence, but because of the political power of municipalities, and incumbent homeowners. These actors often cast themselves as defenders of “community control” or “equity,” but in practice, they wield local process as a blunt instrument to halt even modest reforms. The left’s traditional reluctance to challenge these constituencies—because they are seen as part of the progressive coalition—has created a blind spot. As Klein observes, “The left is often very attentive to power when it’s coming from certain recognized villains… and much less attentive to power when it’s coming from people who might in other contexts look like allies.” If affordable housing is to be achieved, liberals will have to accept that not all obstruction is reactionary. Sometimes, it comes from within the tent—and must be met with the same urgency and clarity of purpose.

Understanding this dynamic is crucial. It means that solutions to the housing crisis can’t be found solely by bashing developers or tinkering with market incentives. There is a fundamental governance challenge: the diffusion of power to 19,000 municipal governments (nationwide) whereas in many areas control land use, often wielded in a hyper-local, exclusionary way. Housing advocates increasingly argue that shelter — like education or civil rights — must be treated as a state (or even national) concern, not left entirely to local vetoes. Indeed, the move toward state-level zoning reform gained momentum precisely “in response to local government intransigence on allowing more housing,” as Dan Bertolet noted. States are recognizing that if every city can unilaterally forbid density or affordable projects, the result is a collective action failure: an entire metro or state ends up with too few homes and skyrocketing rents. Local control, in this view, isn’t a principled defense of democracy but rather a structural obstacle that entrenches NIMBYism and scarcity.

To be sure, proponents of local control believe they are safeguarding community input and tailoring solutions to local conditions. They caution against “one-size-fits-all” laws and argue that growth should come with local planning for infrastructure, green space, and affordability. These concerns aren’t frivolous – any top-down policy should indeed account for differences between, say, rural towns and big cities, and should ideally be paired with resources to help cities upgrade sewers or transit to serve growing populations. But too often, “local control” becomes a catch-all excuse to block any change. In practice, it has meant city councils responding to a loud minority of neighbors who oppose new housing, or simply preserving exclusionary zoning that keeps starter homes and apartments out by design. The broader public, including renters, future residents, and even many homeowners who support more housing, have less voice in these fragmented local debates. That’s why state intervention is on the table: to overcome the collective paralysis of dozens of municipalities each saying “not here” to new housing.

Common Good vs. Parochial Interests

The Colorado and Minnesota experiences in 2025 perfectly illustrate this tension. The narrative of rapacious developers didn’t actually fit the facts on the ground – developers were trying to build housing, but local political structures stood in the way. And when states attempted a gentle nudge, city lobbyists cast the issue as defending regular folks from evil developers or bureaucrats in the state capital. It’s a savvy framing that taps into American sympathies for “small government” and community rights. However, as housing shortages worsen, that framing may lose its punch. More people are realizing that hyper-local veto power has a social cost: it prices out young families, drives workers farther from jobs, and reinforces segregation by income and race (since exclusionary zoning was historically used to keep “undesirable” groups out of certain neighborhoods). In short, the real fight isn’t homeowners versus developers, it’s the common good of housing abundance versus the parochial instinct to say ‘no’.

Good piece! Infuriating of course, but very compelling and clear. Good job getting restacked by Matt Yglesias ... prepare for about a zillion new followers!

Interesting post! I think we have to look at the other side of these policies to understand why it was turned down. the bill in colorado seems like it was just an excuse for religious institutions to earn money while avoiding property taxes. I'm not saying that all religious institutions are like that, but developers could easily take advantage of this to avoid property taxes (make a fake church to make money; one of those mega churches could start building low quality housing and disappearing with all of their money). the bill in minnesota seemed a bit to ambitious. they should have introduced it separately to have a greater chance of getting it passed. I think developers are insanely greedy and local government is trying to protect the people from being victims of their greed. at the same time, i think some local government officials are more interested in appeasing stakeholders who fund their reelection than fixing pressing issues in our community. we all need to be more involved in our local governments and calling our representatives. showing up to public hearings. reading the legislation. it's difficult especially because a lot of us have work and families. local government should do everything they can to accommodate their constituents since they work for us!