It Shouldn’t Be So Expensive to Take Care of People

The cost of taking care of people we love has been outrunning wages for decades. KPMG found that between 1991 and 2024, daycare and preschool costs rose at nearly double the rate of overall inflation. Care.com’s 2026 survey reports that the average parent now devotes about 20 percent of household income to childcare, roughly triple what HHS considers affordable. A fifth of families are spending north of $30,000 a year. And this isn’t a coastal elite problem: center-based infant care fails the federal affordability benchmark in every single state.

At the other end of life, the picture is just as bleak. A private nursing home room now runs about $11,300 per month nationally. Assisted living averages $6,300. Home health aides—often the more humane and preferred option, cost in the range of $6,700 to $6,900 per month, and that’s for basic assistance, not round-the-clock care. These figures rose seven to nine percent in a single year between 2023 and 2024, far outstripping general inflation.

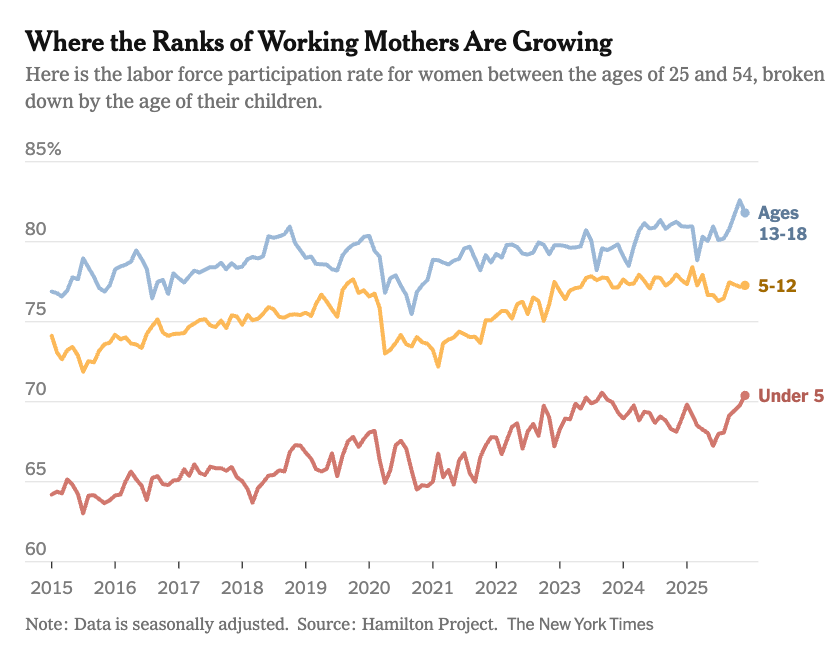

A New York Times report recently explored why mothers of young children remain in the labor force at rates above pre-pandemic levels, and concluded it’s not just about remote work flexibility, it’s about financial necessity. Economists increasingly believe many mothers can’t afford not to work, even when the cost of working (childcare, commuting, the rest of it) makes the math barely pencil out. Hamilton Project data shows participation among women with children under 5 peaked near 71 percent in late 2023 and hasn’t come back down.

Image Credit: The New York Times

What those numbers don’t capture is how families are actually making it work, or are unable to. A new report from Capita, a family policy think tank, cuts through one of the most persistent myths in this debate: that there’s a divide between “working parents” and “stay-at-home parents.” Their research finds that 70 percent of stay-at-home parents do some paid work, often part-time, sometimes full-time, frequently cobbled together around nap schedules and after bedtime. What these families actually are is underserved by every category policymakers have built for them.

Half the stay-at-home parents Capita surveyed said they wanted a paid job but were at least partially blocked by the cost or unavailability of childcare. A majority said they’d work more if affordable nonparental care existed. 69 percent said they could afford no more than $300 a month for childcare, with nearly a third saying it would need to be $100 or less. To put that in perspective, actual costs in even the cheapest states run more than double those figures which means the gap between what families can pay and what care actually costs simply do not match up.

What’s especially revealing is the mismatch between the care families want and the care the system is designed to provide. Nearly half of stay-at-home parents prefer a family, friend, or neighbor caregiver, yet most childcare policy focuses narrowly on full-time licensed center-based programs, leaving informal caregivers largely outside the system.

This is also, notably, an area with real bipartisan potential. Social conservatives who value the choice to have a parent at home and progressives who want affordable childcare for working families are often talking about the same households and Capita’s data shows that supporting both isn’t a zero-sum proposition. There are plenty of issues where the two parties will never find common ground. Family care policy doesn’t have to be one of them.

What does a serious care policy agenda look like?

The New Democrat Coalition’s Affordability Agenda includes national paid family leave, a tax refund for caregiving expenses, a senior care cost-reduction program, and workforce investment in direct care workers. It’s a solid foundation, but mostly incremental, easing costs without restructuring the economics of care.The paid leave plank is the most structurally significant. Paid family leave keeps parents attached to the labor force during the most vulnerable moment of family formation, reduces the income shock that pushes new families into debt, and produces measurably better health outcomes for mothers and infants. Without it, the U.S. remains an outlier among wealthy nations, and the burden falls hardest on low-wage workers, who are least likely to have employer-provided leave. One in four employed mothers returns to work within three weeks of giving birth, and only one in five workers in the lowest-paid jobs has access to paid bereavement leave. We discussed this and more on the Rebuild with Representative Sykes and Chair Representatives Budzinski.

Capita’s recommendations go further, proposing Social Security caregiver credit, At-Home Infant Care programs funded through federal childcare dollars, and real investment in family and neighbor caregivers. The politics work: 60 percent of Democrats and 43 percent of Republicans said stay-at-home parent support would make them more likely to back childcare legislation.

Gene Sperling makes a further case in Democracy that’s worth dwelling on, the same AI that’s reshaping the broader economy can also make care work itself more effective. In eldercare, AI tools are already coaching home health aides through real-time intake assessments, drafting care plans from transcribed conversations, and monitoring fall risk, sleep patterns, and medication adherence around the clock, not to eliminate the aide who shows up, helps someone bathe, and provides the human presence that combats isolation, but to make that aide more effective and catch problems before they become emergencies. This is the case for investing in care work, not against it. The productivity gains AI generates elsewhere in the economy can fund the millions of care positions that are currently missing only because nobody has been willing to pay for them.

The fully refundable Child Tax Credit, which reduced child poverty to record lows during its brief expansion in 2021, needs to be restored. Paid family leave needs to be universal. The care workforce needs compensation that reflects the actual value and difficulty of the work. Social Security needs caregiver credits so that parents who step out of the workforce to raise children or care for aging relatives aren’t punished in retirement. And as Capita’s research makes plain, family policy needs to stop treating the care landscape as a binary between “working parents” who need daycare subsidies and “stay-at-home parents” who need nothing—when the reality is a messy, stressed-out continuum of families improvising solutions that the system was never designed to support.