How to Make Flying Cheaper

More ATCs, More Capacity, and More Competition

The holidays are around the corner, and with that a lot of people will be flying to visit friends and relatives. Whether you realize it or not, you’ll be paying more to fly than you need to. We can make flying cheaper. Here’s how.

An Abundance Agenda for Air Traffic Controllers (ATCs)

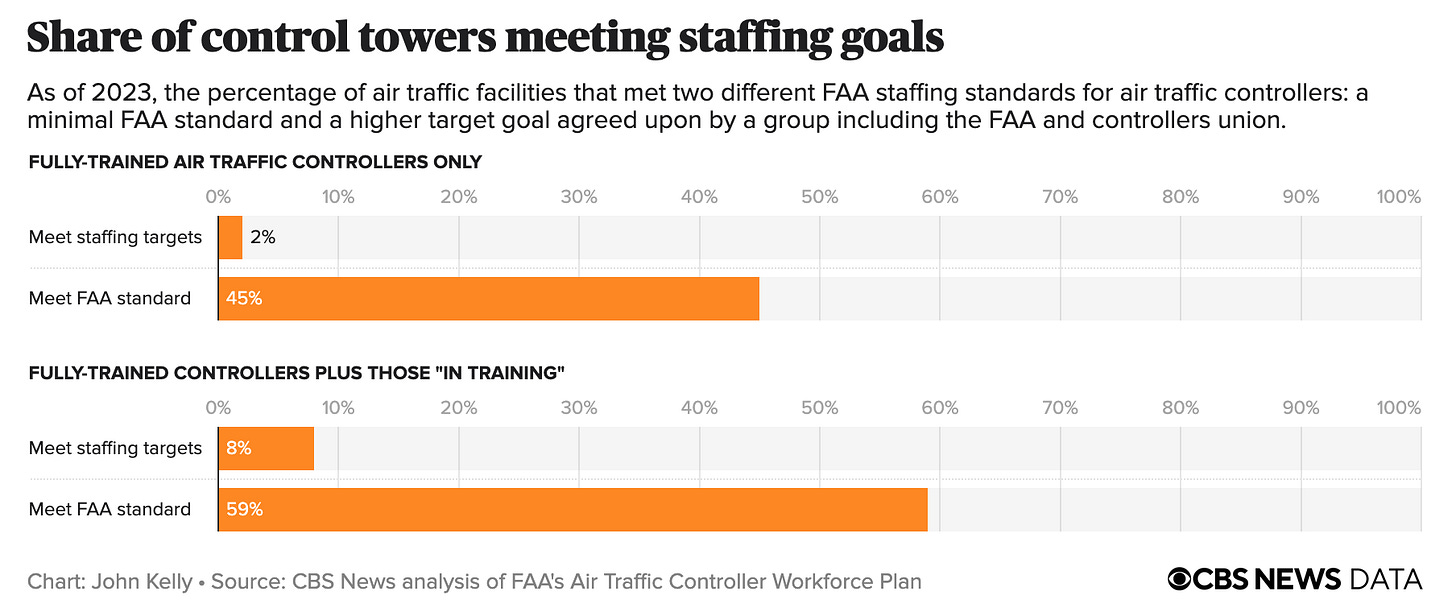

The FAA currently has about 11,000 ATCs, but that puts itabout 3,000 short of target levels, and some major facilities are 15% or more understaffed. That ATC shortagecauses delays, flight cancellations, and reduced capacity at major airports. Even if you count ATCs in training, more than 90% of airports do not meet staffing targets.

Why don’t we have enough ATCs? Several reasons, all of which stack on top of each other. First, the FAA hasn’t been hiring enough, but that’s not entirely their fault because a lot of this reduced hiring was related to multiple government shutdowns, sequestration-related budget cuts, and COVID. Second, the FAA’s ATC Training Academy is too small and undermanned and so that adds another bottleneck. What makes this even more frustrating is that Congressional Representatives from Oklahoma blocked funding for a second training facility because they feared it would take resources from the existing FAA training facility in Oklahoma. That’s right- they effectively NIMBYed expanding ATC training.

The Trump administration has promised new incentives for ATCs eligible for retirement to stay on the job longer. It would be good if that stopped being a promise and started being a reality. There are also plans to build more simulators to speed up training but, even if these plans come to fruition, that’s only going to increase the ATC headcount by about 1,000 by 2028. We need more than that.

We need immediate extra funding to hire more ATCs. Where’s that money going to come from? By having private jets pay their fair share for ATC resourcesMost people don’t realize this but commercial airline passengers pay a 7.5% ticket tax that funds air traffic control. Private jets don’t. They only pay a fuel tax. On a flight from Atlanta to Orlando, the passengers on a commercial flight would collectively pay about $2,300 in taxes. A private jet would only pay about $60. This disparity means that even though private jets are about 7% of all flights managed by the FAA, but they only contribute about 0.6% of the FAA’s fees. Commercial passengers, i.e. regular people, are effectively subsidizing private jets by over $1 billion annually. Taxing private jets based on weight and distance (as Canada does) would mean that private jets would have to pay their fair share of aviation taxes and this could help fund the hiring of those ATCs we so badly need. And, for what it’s worth, this is an area where Abundance and populism would have a natural alignment.

Expanding Airport Capacity

ATCs are not the only thing that we’re short on. We need more runways and more gates. But between concerns about noise, environmental reviews, and the sheer amount of space they take, building a brand new airport is extraordinarily difficult. The average age of the 50 largest airports in America is 82 years (only a little younger than the average commercial flight craft itself) and only three of those were built in the last 50 years. We need to add runways and gates to the airports we already have. We are doing that, but extremely slowly. Between 2000 and 2015, we added just 18 new runways at major airports and extended 7 others. And the Airport Councils International reports that America’s airport infrastructure is critically underbuilt even as it estimate that passenger and cargo air traffic will grow by 150% between 2023 and 2040.

A key reason for slow construction is a significant flaw in an obscure fee called the Passenger Facility Charge (PFC). The PFC is a local airport fee (currently capped at $4.50 per flight segment) that funds airport improvements: new gates, terminal expansions, ground transportation upgrades. Airports decide whether to charge it based on their own needs, and the money stays at that airport to fund local infrastructure.

The problem is that Congress hasn’t adjusted the PFC cap since 2000 and so inflation has cut its purchasing power roughly in half. An airport that could have funded a significant terminal expansion in 2000 now collects only half the real revenue from the same passenger volumes. Simply updating the PFC for inflation and indexing it going forward would give airports stable, predictable funding for the incremental expansions that are actually feasible and that will expand capacity and so ultimately bring prices down further. Reforming the PFC would also make airports less financially dependent on the airlines and so reduce the incentive to have exclusive use gates (discussed below). It’s also worth noting that the consumer loss from lack of gate availability ($5.8 billion annually) well exceeds the entire PFC collection annually ($3.6 billion in 2019) and so PFC funded gate expansion would very likely pay for itself.

More Competition

The first way to increase competition is to allow what’s known as foreign cabotage. Under current U.S. law, foreign airlines are prohibited from flying domestic routes. Lufthansa can fly you from Munich to New York but can’t fly you from New York to Milwaukee. These cabotage restrictions are fundamentally protectionist; they prevent willing buyers and willing sellers from doing business because of the nationality of one party.

Full cabotage (allowing any foreign airline to fly any domestic route) would be great and is correct in principle but probably isn’t politically feasible; the airlines and their unions would vehemently oppose it. But there’s a more limited version worth considering that could have political legs: allow foreign airlines to compete on routes between airports that do not have pressure on their available slots. At airports like JFK and O’Hare, adding foreign carriers wouldn’t meaningfully increase capacity, they’d just be competing for scarce slots. But there’s a category of mid-sized city pairs (Grand Rapids to Nashville, Boise to Albuquerque, etc.) where airports have plenty of capacity, but service is limited because U.S. carriers don’t prioritize these routes. Foreign carriers with different cost structures or network strategies might find these markets viable, especially if they could integrate them with international connections. If Air Canada wants to start trying to serve the Burlington, VT to Minneapolis, MN route, why shouldn’t they be allowed to try? A pilot program of select non-slot-constrained routes could test the concept, that way if it turns out to help, we can see the benefit and, if it doesn’t, at least we know.

A second needed reform relates to exclusive gate leases. Airlines need gates to park planes and board passengers. At many major airports, incumbent airlines control most gates through long-term exclusive-use leases. These leases can create significant barriers to entry. A low-cost carrier wanting to compete at a hub airport may find that every gate is tied up in exclusive leases with the incumbent carrier. Even when gates sit empty for hours, the lease prevents other airlines from using them.

Reform options include requiring shared-use arrangements during periods when the primary leaseholder isn’t using gates, shortening lease terms so gates return to the market more frequently, or tighter use-it-or-lose-it provisions for underutilized gates. The goal isn’t to eliminate long-term leases entirely, but to ensure that publicly-financed airport infrastructure enables competition that will rebound to the benefit of the consumer.

Slot control reform is another policy improvement worth considering. Slot controls are regulatory limits on the number of takeoffs and landings allowed per hour. They still get used at JFK, LaGuardia, and Reagan National. These aren’t arbitrary restrictions: they’re implemented to manage genuine congestion problems at these three airports where demand most exceeds what can be safely handled. But still, the way that these slots get allocated limits competition in ways that are bad for consumers. As long as airlines use their slots at least 80% of the time, they essentially get to keep them indefinitely. Having stricter use-its-or-lose it requirements and making it easier to trade slots on the secondary market could make this process more competitive. Admittedly, this is a limited reform because slot controls are only present at three airports but these three combined handle about 130 million passengers annually (about 15% of the whole U.S. market), so it would help overall.

Build Over Blame, Once Again

Some of these reforms can align Abundance and populism: making private jets pay their fair share is both economically efficient and appeals to populist sensibilities about fairness. The exclusive gates issue fits here too. But the broader and deeper lesson is that most of what makes flying expensive isn’t corporate greed, it’s artificial scarcity. Which means the answer isn’t blaming the airlines, but rather expanding supply.

We’ve made it too hard to train air traffic controllers, too expensive for airports to build gates, and too difficult for new airlines to compete. The solution isn’t going to war with the airlines or imposing price controls like we did before the Airline Deregulation Act of 1978. That era gave us higher fares, less service, and airlines that couldn’t compete on price. Targeted deregulation worked because it allowed supply to expand and competition to flourish.

That’s the flight path. Train more ATCs. Build more runways. Open more gates. Reduce protectionist cabotage regulations. Allow more competition. This is how we make flying cheaper so that you can travel for less.

-GW

You mentioned Canada: they are notorious, AIUI, for having successfully privatized their ATC system. Is there a reason that ATC privatization didn't make it onto your list of reforms?

You can combat fortress hubs by mandating that no more than 40% of gates/slots are owned by any airline/alliance. That would being competition to ATL, CLT, DFW, MSP etc