How to Actually Make Gas Prices Go Down

It Ain’t Looting Venezuela

Unless you live under a rock, you saw that the United States captured the President of Venezuela Nicolas Maduro. This is a momentous and fast-moving event, but it also has a tangential connection to the cost-of-living (the focus of this newsletter).

One of the main arguments that Trump has made about why the United States captured Maduro is that it’s about oil. Let’s put to the side all of the problems associated with asserting that we should simply steal Venezuela’s oil (and there are many). Instead, I want to ask a simpler question: if we aren’t going to steal Venezuelan oil – and there are a lot of problems with this idea anyway – how exactly do we make gas prices go down? There are several ways to do this, facilitating a faster rollout of electric vehicles so we reduce demand for gasoline to give just one example, but today I want to focus on an idea that gets far less attention: making it easier to build new oil refineries in the United States.

Yes, We Do Want Cheaper Gasoline

Sometimes, I will hear an economist or climate activist argue that gasoline should be more expensive given the negative externalities of carbon. While I understand the theoretical case for that argument, the fundamental fact remains that the vast majority of voters want gas prices to go down, not up. They have places to go and, outside of 4-6 metro areas, you simply must have a car to get around.

Gas prices are thus very salient. Democrats need to loudly cheer for lower gas prices and if that annoys a few of the environmental NGOs, then so be it. The way out of the climate change problem is technological innovation, not driving up the cost of getting around for everyday Americans.

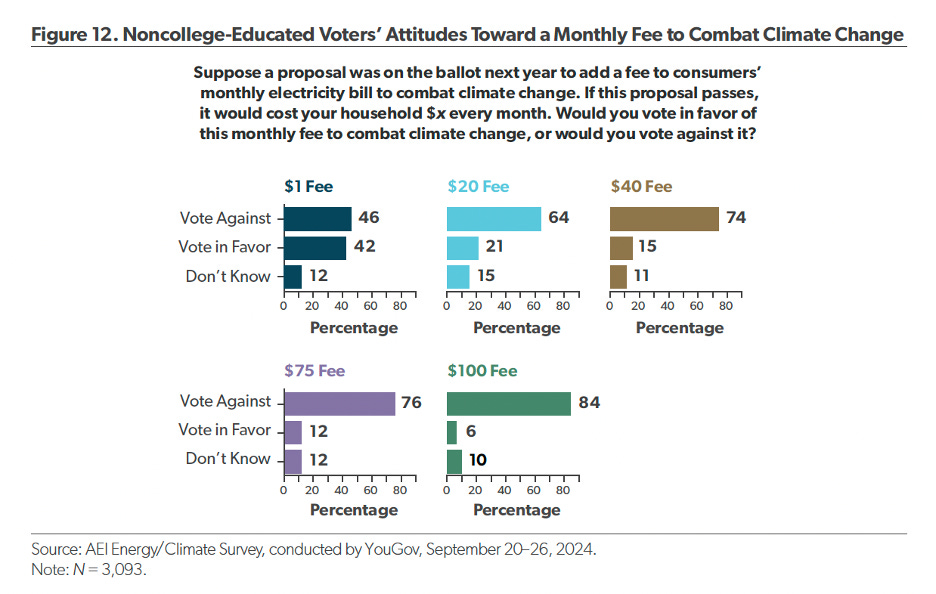

Asking people to sacrifice for climate action has been proven, time and time again, not to be a political winner. Polling shows that non-college voters are effectively split on climate action if it costs even $1 a month; they turn against it sharply as costs rise.

Democrats need to internalize this as a fact and make our peace with it.

Constrained Refining Capacity Increases Costs

Believe it or not, the newest major oil refinery in the U.S. was built back in 1977. We have built very few new refineries over the last few decades, while a number of refineries have closed. In 1982, the U.S. had 254 refineries in operation; today we only have 131. This combination of no new refineries and old ones closing has created a serious supply constraint. It means that even as some refineries have added capacity, overall capacity has barely budged. In 1982, we could refine about 17.9 million barrels of oil per day; today, that stands at 18.4.

American refineries now routinely operate at 90-95% capacity, meaning there’s virtually no slack in the system. When a hurricane forces Gulf Coast refineries offline, or when unexpected maintenance hits a California facility, prices immediately spike because there’s no spare capacity to fill the gap.

Building New Refineries is Actually Good for the Environment

I’m sure that some readers are thinking “ok, but won’t building new refineries be bad for the environment?” Actually, no. The refineries we rely on now were built in the 1970s or earlier. They’re less efficient, emit more pollutants, and have less effective, retrofitted pollution control technologies. When those older refineries expand capacity, they aren’t subject to the same level of regulation as new refineries. But we keep them running precisely because we’ve made it virtually impossible to build cleaner replacements.

New refineries would be built with modern pollution controls that didn’t exist in the 1970s. Adding cleaner, more efficient capacity means the refining sector overall would become cleaner per gallon produced, even as total capacity increases. And as electrification reduces gasoline demand over time, the oldest and dirtiest refineries will be retired.

This is a very important point for my environmentalist friends already warming up the comments section – it will not make economic sense for these refineries to continue to operate. Companies will not want to lose money, and will shut those older, dirtier refineries down. Finally, there is a whole range of carbon emissions reducing innovations that can and should be adopted, but importantly, that is a lot easier to do for newly built refineries than for old refineries.

So Why Don’t We Have New Refineries?

If new refineries would increase capacity, reduce price spikes, and operate cleaner than aging facilities, why hasn’t anyone built them? The answer is a combination of permitting dysfunction and rent-seeking by incumbents that profit from artificial scarcity.

Let’s start with the permitting nightmare. Building a refinery requires approvals from the EPA for air quality and water discharge, state environmental agencies, local zoning boards, and potentially the Army Corps of Engineers. This gauntlet can take many years before construction even begins, and that’s on top of the several billion dollars in capital costs. Businesses are very hesitant to make that investment when permitting timelines are uncertain and any individual agency can unilaterally delay or kill the project.

Environmental regulations also compound the problem. The Clean Air Act requires new facilities to meet stricter pollution standards than grandfathered existing refineries, which is appropriate – you want industry getting cleaner over time. But importantly, there’s no expedited path that recognizes building modern capacity as an environmental improvement. A new refinery with state-of-the-art emissions controls faces the same years-long review process and legal challenges regardless of how much cleaner it would be than the aging plants it might eventually help retire.

The prospect of lawsuits doesn’t help either. As one law professor candidly put it, “If I was trying to toss a grenade to slow down a new refinery or a major expansion, I would look for federal approvals that trigger a requirement to prepare an environmental impact statement.... even if you can’t stop a refinery project outright, you can slow it down and effectively kill it with a thousand paper cuts.”

And here’s something else to keep in mind: existing refineries benefit enormously from this dysfunction. Limited capacity means higher profit margins. When refineries operate at 95% utilization and supply is perpetually tight, companies can charge premium prices. Why would incumbents push for permitting reform that would allow new competitors to enter the market and compress those margins? They wouldn’t and they don’t. Oil and gas production companies may want permitting reform so that we can more easily refine the light crude we make in the United States, but the refiners are consolidated incumbents with a direct interest in the status quo.

The result is a set of regulatory policies that block cleaner infrastructure, inflate costs for consumers, and pad profits for incumbent producers.

We Don’t Need Venezuela’s Oil

Trump claims we attacked Venezuela to secure oil supplies. But we don’t need Venezuelan oil. The United States has abundant crude petroleum reserves and world-class production and refining expertise. What we lack isn’t resources. It’s the capacity to refine the oil we produce. We’ve made it functionally impossible to build the refining capacity we need. The result is price spikes that hurt working families.

Want cheaper gas? The answer isn’t invading oil-producing countries. It’s permitting ourselves to build the refining infrastructure we need.

-GW

Great work.

Before reading through to the end, I already knew what the problem was: regulation and permitting.

America, and indeed much of the Western world, has self-regulated into preserving 20th century technology and infrastructure. Specifically, it's almost as if society became frozen in 1970.

The relatively unregulated world of micro-electronics has advanced rapidly, but the infrastructure that underpins everything else, from trains to power plants, is hopelessly stuck.

The environmental regulations intended to clear the air, water, and reduce our environmental footprint are paradoxically forestalling our ability to reduce that footprint.

This refinery capacity argument is really well constructed. The permitting bottleneck creating incumbent rent-seeking is classic state capacity erosion disguised as environmental protection. Had a conversation in 2023 with somone who worked EPA reviews and they basically admitted the process is designed to attrition. The part about newer refineries being cleaner but facing harder regulations than grandfathered plants is absurd policy design that actively prevents enviromental improvement.