Green Energy’s Achilles Heel- And How to Fix it

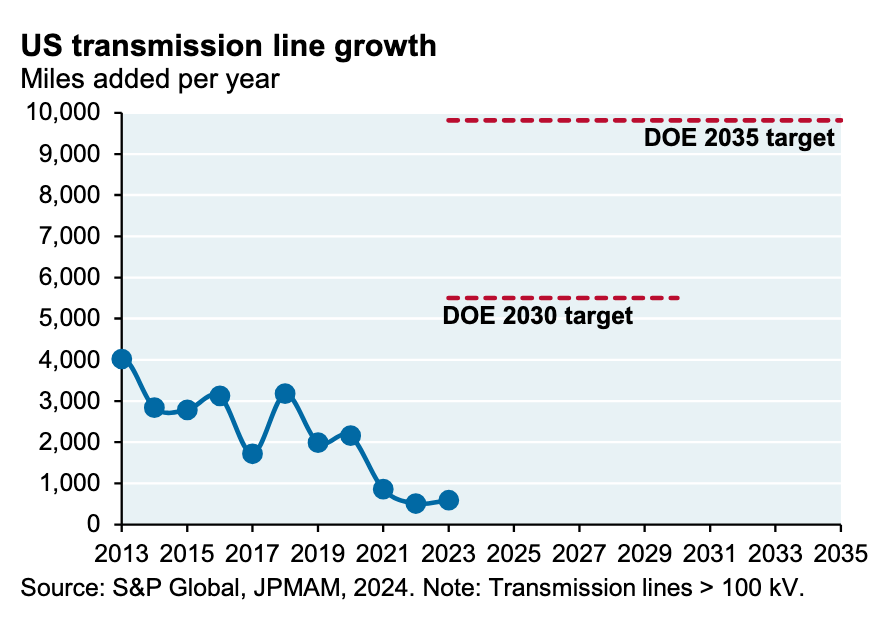

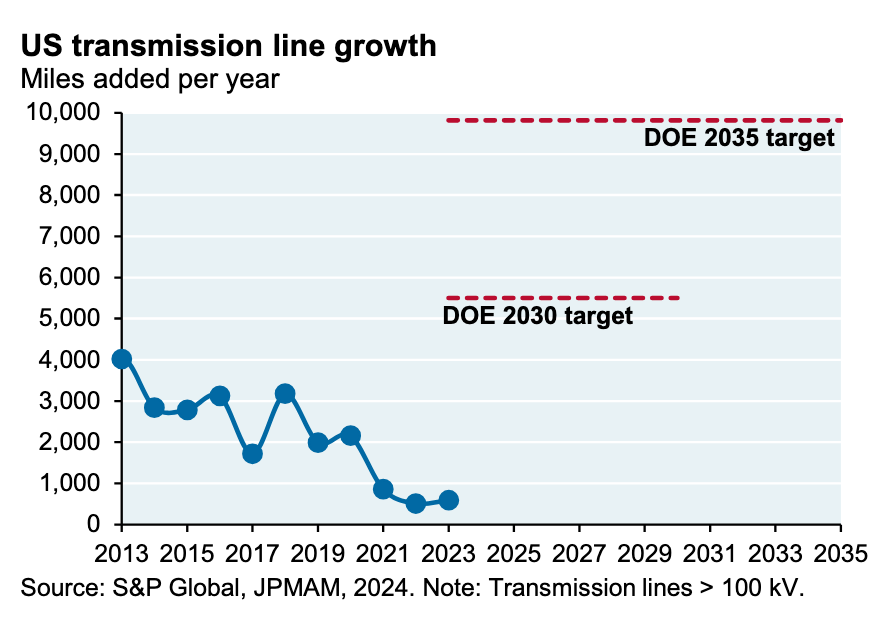

A seriously worrying chart.

The Chart

In my profession, I see a lot of charts. So many charts. Every now and then, a chart really worries me. There was a nightmare chart on urban-rural divides that came out about a decade like this. But I recently saw another one that is very concerning.

This may seem boring and unremarkable, but let me explain what this is showing and why it’s such a problem. Then I’ll discuss how we fix it.

The Problem

New American factories need electricity. Electric vehicles need charging. More computing means more data centers, which require more energy. Electricity demand is expected to grow significantly over the next 5 years and beyond. While natural gas is helpful in many ways, it is a limited resource; if we want to have true energy abundance -so much electricity that it’s cheap- solar and wind have to be part of the solution too.

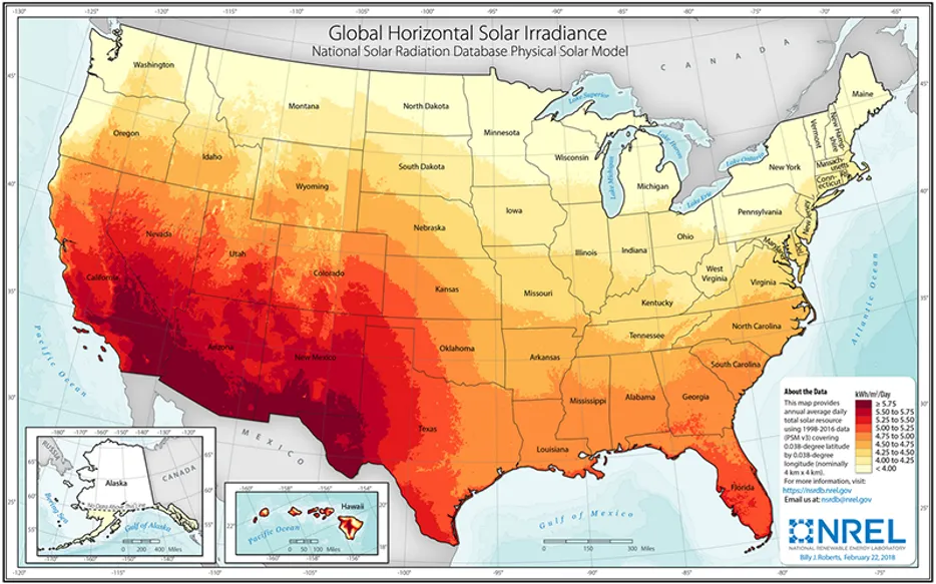

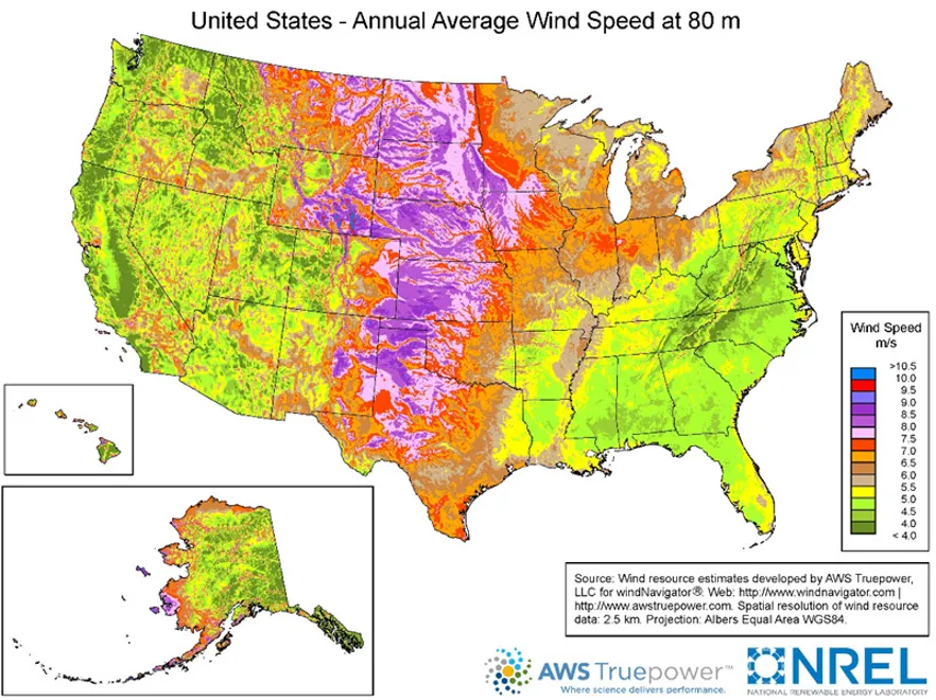

First, some good news. Solar and wind energy production capacity are accelerating at a remarkable rate, which is good because more clean energy production increases the supply of electricity, bringing down costs for consumers and fighting climate change. The combination of solar and batteries is really taking off and that’s helpful in all kinds of ways too, from vehicles to appliances. And there’s plenty of room for growth. The United States is blessed with large solar and wind energy resources.

Here’s the bad news. As you can tell from the maps, the places where it makes the most sense to build a lot of this new green energy are frequently not close to the places where people want to consume that electricity. Parts of the Southwest are solar bonanza but, except for Phoenix and Las Vegas, there aren’t many cities there. Wind is strongest in the Great Plains. Again, that’s an incredible resource but there aren’t many cities there.

To take advantage of much of that green energy potential, we have to move it from where it’s made to where it’s needed. You also need to be able to move electricity around to make the grid more reliable. This means we need high-capacity transmission lines to efficiently move electricity. And we need a lot of them. This is where we get back to that worrisome chart.

The Department of Energy thinks we need to be building more than 5,000 miles of these kinds of transmission lines per year by 2030 and 10,000 miles a year by 2035. To state the obvious, we are nowhere close. In fact, we’re going in the wrong direction. If we don’t fix this, we face an energy future that’s far more painful and costly. We’ll face some combination of higher energy prices, less electricity reliability, fewer jobs, and delayed climate action. Probably all four. That’s why this chart scares me.

We simply aren’t moving fast enough. Last year, the Biden Administration promulgated Order 1920, which updated planning requirements and made some helpful reforms to cost allocation. Meanwhile, the Big Wires Act currently before Congress also helps with cost allocation by having the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) allocate costs if regions can’t agree and mandates a minimum interregional capacity. But neither of these moves take aim at the main reasons why we’re having such trouble building these high-capacity transmission lines: complex multi-state permitting, the pass-through problem, and NIMBYs.

The Three Interlocking Challenges

The fundamental problem is that building interstate transmission lines requires navigating a regulatory nightmare that would make Kafka cry. Unlike natural gas pipelines, which get streamlined federal approval, electricity transmission must secure permits from every state they cross. Each state has its own siting requirements, environmental laws, zoning ordinances, and eminent domain rules. A project crossing five states might need approval from dozens of different agencies, each with different standards and timelines.

This connects to what experts call the "pass-through problem." States have little incentive to approve transmission lines that primarily benefit other regions. Why would Missouri welcome a transmission line that moves wind power from Kansas to Illinois? Missouri bears all the local disruption (construction, visual impacts, land use) while Illinois gets the cheap electricity. It's a classic collective action problem where the costs are local but the benefits are distributed nationally.

Then there's the NIMBY factor. Even when state regulators support a project, local opposition can kill it. Property owners worry about land values, communities object to industrial infrastructure, and environmental groups sometimes oppose lines through sensitive areas. Since transmission projects need continuous right-of-way for hundreds of miles, opponents have countless opportunities to delay or derail construction through lawsuits, permitting challenges, or local political pressure. And as the R Street Institute points out, “Transmission permitting predominantly relies on public engagement to achieve siting consensus, as opposed to using eminent domain to obtain rights-of-way. While understandable, this tilts permitting outcomes toward projects with minimal objections, rather than those that maximize net benefits.”

These three barriers work together to create a system where transmission projects that everyone agrees are needed in principle become nearly impossible to build in practice.

Strengthening FERC’s National Siting Authority

Strengthening FERC’s national siting authority would eliminate the multi-state permitting nightmare, override those pass-through state objections, and create predictable timelines that make projects financeable. Studies suggest this could cut transmission development time roughly in half, unlocking enormous economic benefits. Better interregional connections could save American consumers $47 billion annually while making the grid more reliable and enabling massive clean energy deployment.

But for this to work, Congress needs to grant FERC several essential powers. First, it needs exclusive federal jurisdiction over interstate transmission projects, no more state-by-state approvals. Second, it needs federal eminent domain authority that can override state objections, including the power to condemn state-owned lands. Third, it should have a streamlined environmental review process with FERC as the lead agency and strict timelines. Fourth, there should be explicit authority to allocate costs across regions based on benefits, ending the cost allocation disputes that kill projects.

Think of it as creating a "Federal Transmission Act" modeled on the Natural Gas Act. Projects would need to demonstrate they serve the public interest, but once approved, they'd get automatic eminent domain authority and preempt conflicting state laws. It is important to highlight that this isn't unprecedented federal overreach, it's applying the same regulatory framework we already use successfully for natural gas infrastructure to electricity infrastructure. We already do this for natural gas (to great effect)... let’s do it for electricity!

Why Haven’t We Already Done This?

One predictable vein of opposition comes from state utility commissioners organized through the National Association of Regulatory Utility Commissioners (NARUC). These commissioners are just defending their turf.

More puzzling is Republican opposition, given that Republicans originally created federal transmission siting authority in the 2005 Energy Policy Act. Yet when recent legislation proposed clarifying this authority, Republican senators objected. This represents a complete reversal from the party that championed federal infrastructure authority under President Bush. It appears that at least some Republicans now seem more concerned about opposing anything that might facilitate renewable energy than supporting the efficient energy infrastructure they once advocated.

A perhaps even more surprising source of opposition is environmental groups. One would think they would be thrilled with green energy but that seems to not be the case for some of these organizations who seem to think that the answer to climate challenges can only ever be ‘build nothing and harangue corporations.’ Environmental organizations have opposed this kind of transmission build-out from all the way back in 2008 up through projects in Virginia last year and in Maine just last week.

This is frustrating because there’s a potential win for everyone here. Republicans can like the cheaper energy while environmentalists should be able to appreciate the climate benefits. Hopefully this proposal for stronger FERC authority in electricity that matches its authority in natural gas could get enough Republicans and Democrats on board to get passed.

Using the Interstate Highway System Would be an Early Win

National siting is unlikely to be a reality in the near-term. , and we need to get to work. One good idea is co-locating high-capacity transmission lines along interstate highways. The Federal Highway Administration already has significant authority over interstate corridors, and a 765 kV transmission line needs only 200 feet of right-of-way - easily accommodated along most highway corridors. This would essentially create an "electric interstate system" built alongside our transportation infrastructure.

The benefits are compelling. Using existing federal rights-of-way eliminates the most contentious aspect of transmission development - land acquisition battles with private property owners. It builds on established federal authority that's already widely accepted, making it politically easier than comprehensive siting reform. The strategic placement works well since interstate highways connect major economic centers where electricity demand is highest. Plus, co-location would enable widespread Level 3 DC fast charging stations for electric vehicles, creating a powerful narrative about building integrated 21st-century infrastructure.

However, this approach has limitations. Interstate highways don't reach everywhere transmission needs to go: you might miss more promising renewable energy zones or critical grid connections. Engineering constraints mean following highway routes rather than optimal electrical paths, potentially creating longer, less efficient transmission. Some highway corridors lack adequate space, especially in urban or mountainous areas. But these strengths and weaknesses actually make highway co-location an ideal "early wins" strategy. It could deliver an important segment of needed transmission capacity while demonstrating federal leadership and building political momentum. Success with highway corridors would prove the concept and create pressure for broader federal siting authority to handle the remaining transmission needs.

America's clean energy future depends on building vastly more high-capacity transmission lines, but our state-by-state permitting system makes this nearly impossible. We need federal siting authority for transmission lines just like we have for natural gas pipelines. Starting with interstate highway corridors could prove the concept while Congress works toward more comprehensive reform. The stakes are too high to accept the status quo that that worrying chart above represents.

-GW

I'm delighted to see you notice the obvious: we have already invested huge amounts of money and effort in our interstate highway systems. Now overlay those solar and wind maps with interstate maps. Then move the "cities" to the most favorable energy intersections.

Most of our big cities are where they are because of logistics: first water transport, then "post"-al roads and stagecoaches, then rail, now ICE vehicles. EVs will still use those routes.

Of course, new dense areas would have to be designed for Net Zero and families+community first. But that can and is being done. And don't forget that Net Zero is easier when need is reduced. Very local geothermal and solar, on the building lot or neighborhood level, could reduce seasonal need for added heating and cooling, freeing up what wind and solar there is for those data centers.

Oh, and if there are objections to wind farms because of noise or they're "ugly" (I happen to like watching "wind dancers"), hire some Broadway sound and lighting designers to turn them into tourist attractions.