Diagnosing the Vibescession

Why Naming the Problem Makes Us Hopeful

In almost every poll focused on young people, Gen Z—Zoomers—come across as deeply disillusioned with the world, politics, the direction of America, and institutions as a whole. In a recent CNN poll of Americans under 45, 51% said hard work no longer guarantees success. Among those under 30, that figure rises to 53%. Nearly 40% of respondents under 45 said neither party represents them on the economy. That’s a crisis. I was born in late ’98, so while I sometimes mentally classify myself as a Boomer, I’m very much a Zoomer. Still, I think it’s important to understand the variations within Gen Z if we want to make sense of where this is coming from; in order to move forward, especially when it comes to the Democratic Party’s ongoing struggles with governance.

That’s what struck me at Welcome Fest, or Abundancepalooza as many online were calling it (and some other less charitable terms), this won’t be a recap or a piece regarding The Groups, others have already written that piece. I want to focus on a connection I noticed between a smaller, less-attended morning panel on Gen Z disillusionment and a bigger, buzzier one later featuring Marshall Kosloff, Derek Thompson, and Rep. Jake Auchincloss. That second panel centered on the concept of Abundance, how it can read as optimistic, even when it’s rooted in a diagnosis of everything that’s gone wrong.

Two Generations Under One Label

Rachel Janfaza, a writer for The Up and Up, a blog on the political, cultural, and civic forces shaping Gen Z, is the creator of this chart which splits Gen Z up into two categories, 1.0, and 2.0.

This graph alone went viral back in February and caused a ruckus online, some who were glad to see diagnosis to the vibe switch from elder Gen Z and the younger group, and those who thought this was too neat of a split. But that’s what always happens when you try to bring specificity to something vague and messy—it becomes polarizing. (Bookmark that line—it’ll come back later.)

I wasn’t familiar with Rachel Janfaza’s work before, but I’d seen her chart, and I was curious to hear what she had to say. To be honest, a lot of people talking about how Democrats can win back young voters miss the mark. We’re a tough crowd, and the counterculture often outweighs the positive—basically, everyone’s a critic. Janfaza’s main point was that the defining split in Gen Z is the pandemic: whether you graduated high school before or after COVID hit shapes everything.

The result is a generational divide where older Gen Z might still carry embers of idealism, while younger Gen Z leans into ironic apathy or outright pessimism. In the 2024 election, both sub-groups shifted somewhat to the right out of disillusionment, a notable break from what was expected of youth to be the solid liberal class. It is important to note how pronounced this shift was, the recent Catalist breakdown had staggering results:

“After years of historically high support among Democrats, a significant share of young voters swung toward Republicans. Voters under the age of 30 dropped from 61% Democratic support in 2020 to 55% in 2024. Similar support drops are evident when examining voters by generational cohorts, such as Gen Z or Millennials. These drops were larger than drops for any other generation or age group, and other trends in the demographic data, such as drops among different racial groups and the gender gap, were more pronounced among young voters than the rest of the electorate.”

Janfaza traces this rightward shift partly to the politics of pandemic restrictions themselves. While Gen Z 1.0 was known for being liberal and "on the front lines of many social movements," the older Zoomers begrudgingly stuck with their ideals (narrowly backing Democrats) albeit with frustration, recent headlines show segments of the Gen Z 2.0—particularly young men—gravitating toward Trump and conservative positions.

It was largely Democrats who were in charge keeping these pandemic rules in place, she observed, while Trump and Republicans positioned themselves with anti-restriction rhetoric. For young people experiencing normal developmental frustrations during lockdowns, the political blame often fell on those enforcing the policies that confined them. Gen Z’s younger half is rightfully angry because they were handed a world of broken promises and told to make do.

The Abundance Paradox

By the time we get to the later panel with Thompson and Auchincloss, that thread of disillusionment reappears—but in a different form. Derek Thompson’s talk was a rapid-fire list of everything America can’t seem to build: housing, energy projects, infrastructure. And yet... he noted that the response he would receive from the book Abundance, was one of positivity. Why?

Because he gave it specificity.

Thompson himself has reflected on this paradox: “When people feel a vague sense that [stuff] is broken there's a kind of optimism that's inherent to specificity that even without trying to sound optimistic or hopey-changey, just telling people that they're right about their vague spectral feeling that [stuff] is broken that housing can't be built that energy can't be built that government doesn't work that we can't invent..Being able to be really specific about ‘I know I think why you're upset it's because this rule is getting in our way, It's because this process is getting in our way.’”

In other words, specificity feels like progress. By clearly naming what’s wrong, we feel one step closer to fixing it.

But this isn't just abstract theory, we can see this pattern playing out across multiple domains. Consider how mental health discourse has evolved. A generation ago, saying "I'm depressed" was often dismissed as weakness or self-pity. Today, with specific diagnostic frameworks, treatment protocols, and neurochemical explanations, that same statement becomes the first step toward recovery. The suffering hasn't lessened, but the pathway to addressing it has become visible.

Gen Z 2.0’s malaise isn’t random – it has specific causes (institutional failures, social isolation, economic anxieties). By identifying these, we can begin to formulate solutions or at least regain a sense of agency. Abundance does exactly that for America’s policy failures: it “diagnoses” why we can’t build things or solve big problems, drilling into zoning laws, bureaucratic red tape, and political incentives. That act of facing the facts head-on – however painful – paradoxically gives readers a dose of optimism, because now we know what specific hurdle to overcome. Likewise for Gen Z: if we articulate why we’re so distrustful (e.g. “our capacity to see problems has sharpened while our ability to solve them has diminished” in recent decades), we are already moving toward change. Specificity, in this sense, is empowering. It turns amorphous dread into concrete challenges we might actually tackle.

The Data-Vibes Disconnect

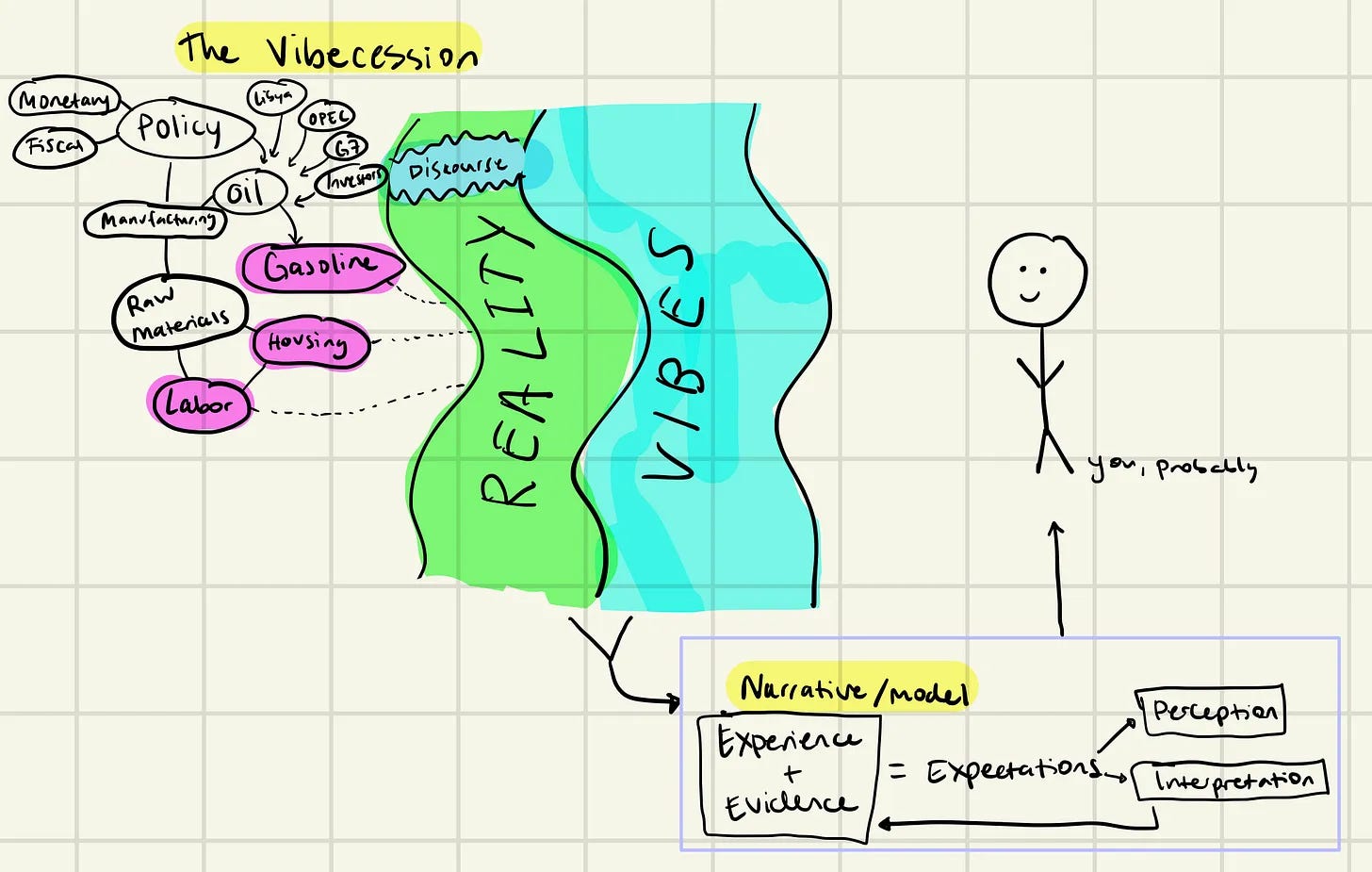

This connects to what economist Kyla Scanlon calls the “vibecession”. It’s not a technical recession. It’s a psychological one. A moment when all the macro indicators; GDP, unemployment, consumer spending, look pretty good, but the vibes are deeply off. And crucially, the dissonance between what we're told and what we feel isn't imagined. It's signaling something real.

Image Credit: Kyla’s Newsletter

Scanlon coined the term during the post-pandemic economic recovery, when inflation was easing and employment was high, but Americans across demographics still felt pessimistic, anxious, and financially insecure. In that moment, Gen Z stood out, not because we were economically worse off on paper than everyone else, but because we were culturally and emotionally attuned to the mismatch. We’re the generation raised on dashboards and data, yes, but also on memes, vibes, and hyper-online pattern recognition. When the narrative doesn’t match the lived experience, we don’t just notice, we internalize it.

The vibecession reflects a deeper crisis of institutional credibility. When official statistics say everything is fine but lived experience suggests otherwise, people start questioning not just the statistics, but the institutions producing them. This erosion of trust creates a feedback loop: the more disconnected official narratives become from felt reality, the more people withdraw from civic engagement, which weakens institutions further.

The vibecession isn’t just about bad vibes. It’s about structural opacity. We sense that the systems around us, housing, healthcare, education, governance, aren’t working. But until recently, no one was explaining why. No one was walking us through the pipeline of dysfunction that turns a zoning law into unaffordable rent, or a permitting delay into climate stagnation. What Kyla named as the vibecession, and Rachel Janfaza aptly defines within the two groups of Gen Z, Derek Thompson and Ezra Klein diagnose in Abundance. And that’s where these ideas converge: specificity is the start to finding the cure for the vibecession.

When You Name It, You Can Fix It

When people are stuck in a fog of generalized malaise, specificity is a beam of light. It doesn’t fix everything, but it lets you see the terrain. That’s what Abundance offers. And it’s why the book, despite being a relentless catalog of “everything that’s broken,” reads as optimistic. It doesn’t just tell you the vibes are bad, it explains, systematically, why they are bad. It replaces ghost stories with real bottlenecks. And that shift from vague unease to concrete explanation, is transformative. It’s the moment when you realize your gut feeling wasn’t paranoia, it was pattern recognition.

Progress will feel slow at times, but as we’ve learned, even feeling progress can begin with simply identifying the next rung on the ladder. Specificity gives us that rung. And climbing, one step at a time, is how we reclaim an optimistic future.

There is a similar split among Baby Boomers. Those born ~1958 and after were quite different from our predecessors. (I was born in 1960.) We grew up during the chaotic, financially stressed 1970s when everything seemed to be going to hell. We also leaned Republican in our youth.

Quoting an October 16, 1984 NYT article: "Ronald Reagan, at the age of 73 the oldest President, is more popular with young voters than with any other age group, according to a number of polls. Many disagree with some of his policies, but he is coming across to young people as a firm yet kindly grandfather figure, a leader who inspires confidence in an uncertain world. 61-to-30 Over Mondale According to combined figures from the two most recent New York Times/ CBS News Polls, taken before the Presidential debate on Oct. 7, voters from the ages of 18 to 24 supported Mr. Reagan by 61 percent to 30 percent over his Democratic challenger, Walter F. Mondale. For the rest of the electorate the margin was narrower, 53 to 32. Polls indicated some shift in public opinion after the Presidential and Vice- Presidential debates, but there was no indication of a marked change in the youngest age groups."

Time article making the same point: https://time.com/archive/6700984/reagans-youthful-boomlet/

Reagan's appeal was a lot more like that of Abundance than that of Trump.